Few foreign writers understand Sri Lanka as deeply as Ajay Kamalakaran does. Since falling for the island in 2003, this Mumbai-born, Palakkad-rooted journalist—raised in New York and seasoned in Russia—has returned almost every year, travelling from Colombo to Jaffna, learning Sinhala, and excavating the forgotten histories that lie beneath Sri Lanka’s surface.

Over time, his writing has brought back into view stories that quietly slipped out of public memory: the old Boat Mail that once carried passengers from Egmore Station in Madras to Colombo Fort; the distinctive Tamil dialect still spoken by fishermen in Negombo; and the forgotten cultural and historical links that bind India and Sri Lanka far more deeply than contemporary politics suggests.

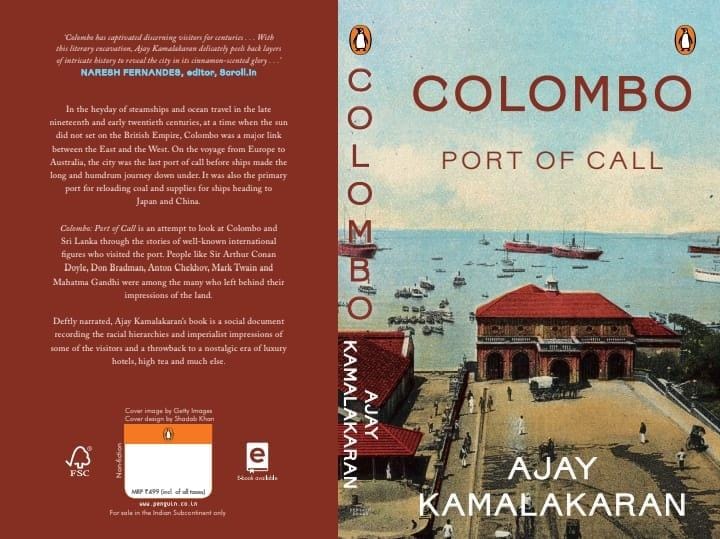

Now, with his new book Colombo: Port of Call—set for release this month by Penguin Random House—Kamalakaran reconstructs the port city's golden age, when it stood as one of the world's great maritime crossroads. Through the eyes of travelers ranging from Mark Twain to Mahatma Gandhi, from Crown Prince Hirohito to Don Bradman, he reveals a Colombo that was simultaneously a gateway to paradise and a stark monument to colonial inequality.

"Sometimes I feel I was born on the wrong side of the Palk Strait," Ajay Kamalakaran tells me. In this wide-ranging conversation, we discuss why he believes travel builds bridges in ways politics never can, why the Boat Mail should be revived, and what it means to write honestly about empire without romanticizing the "good old days" that were never good for people like us.

Could you tell us a little about yourself and your latest book, Colombo: Port of Call?

I was born in Bombay—which I still prefer to call Bombay; I’ve never really warmed to the name Mumbai—and I was partly raised in the United States. A significant part of my professional life, however, has been spent in Russia, a country I feel deeply connected to. I speak the language, and I associate a strong sense of belonging with the place.

Professionally, I work as a journalist and writer and have contributed to a range of publications, including mainstream media outlets. What particularly interests me as a writer is history—specifically, historical connections as a way of bringing people together.

History is often used to divide societies. While I don’t believe in erasing the darker chapters of the past, I do think there is immense value in identifying shared histories and legacies to celebrate together. If there are stories that can foster understanding and connection, I feel they deserve to be told.

For instance, in 2021, I wrote an article that became quite popular in Sri Lanka about the Boat Mail—the journey one could once take from Egmore Station in Madras all the way to Colombo, via Talaimannar, using ferries from Dhanushkodi, and later Rameswaram. That story resonated deeply with people on both sides of the Palk Strait, precisely because it evoked a shared past.

I’ve also written about lesser-known Tamil dialects, such as the one spoken in Negombo, and explored forgotten links between India and Sri Lanka. My broader aim is to trace these connections—between India and the wider world—and to rediscover legacies that unite rather than divide.

I’m very conscious of the impact a historical piece can have, and I think deeply before committing to a subject. That sense of responsibility shapes my writing.

In addition, I write a regular column for Malayala Manorama’s English platform, On Manorama, where I explore historical and cultural connections between Kerala and the rest of the world. Through this work, we’ve uncovered fascinating, often forgotten links between Kerala and Sri Lanka. We also discovered connections that were largely forgotten because, following the unfortunate events of the early 1930s, many Malayalis left Sri Lanka en masse or chose to maintain a very low profile. Yet there is so much to celebrate in shared history and commonalities, and that is where my focus lies.

As for my books, I’ve previously written a collection of short stories set in the Russian Far East, where I once lived, as well as a novella set in Moscow in 2015. Colombo: Port of Call is my first major work of nonfiction. I wrote a guidebook many years ago titled Sakhalin Unplugged in 2006.

Colombo: Port of Call represents my first full-length, deeply researched foray into nonfiction writing.

You spoke about the mass exodus of Malayalis in the 1930s. Could you tell us what happened during that period?

What happened is not widely remembered today, although it is well documented. In the 1930s, there was a strong anti-Malayali sentiment in Ceylon, and archival records contain considerable information on this. Unfortunately, Malayalis were seen as people who were taking away jobs from the Sinhalese population.

What is also important to note is that even leftist trade unions turned against the Malayali community at that point in time. There were calls for social boycotts, and as a result, quite a few people left the country.

At the same time, many Malayalis chose to stay back but kept a very low profile. A large number of them eventually married Sinhalese women, and even today, you can find people who have retained their Kerala surnames—such as Menon—who are Sri Lankan citizens and whose families have lived in the country for several generations.

I think what happened in the 1930s shaped the community in a lasting way. It made them cautious and less visible, leading them to avoid standing out, unlike Malayali communities in other parts of the world.

Have you visited Jaffna before, and what was your experience like?

There’s a deep sense of familiarity that I feel in Jaffna, and it makes me genuinely happy. I think part of it comes from my background—I speak what you might call Palakkad Tamil. Interestingly, it sounds quite close to Jaffna Tamil in many ways.

On one of my Chennai trips, when an auto driver heard my Tamil, he kept asking me “Slona, Slona.” It took me time to figure out that he was actually asking me “Ceylona” or whether I was from Ceylon. I was a bit confused—because in Russian, sloan means “elephant.”

Most people from Palakkad are bilingual. We are comfortable in both Tamil and Malayalam. That’s the beauty of border regions anywhere in India.

You were born in Mumbai, raised partly in the United States, and spent much of your professional life in Russia. How did your interest in Sri Lanka begin?

It actually began quite unexpectedly. About 24 years ago, I met someone from Sri Lanka in Calcutta. We were both travelling to the Himalayas—Darjeeling and Sikkim. We happened to be staying at the YMCA in Calcutta, and when I told the receptionist that I was taking a particular train to Darjeeling. He mentioned that a young Sri Lankan gentleman would be on the same train and offered to introduce us.

Looking back, it feels predestined. We met, got along extremely well, and became the closest of friends. At that time, I must admit, I had rather misguided ideas of Sri Lanka. This was shaped by cricket rivalries and the strained diplomatic atmosphere following the events of the late 1980s. My views, like those of many Indians then, were largely coloured—and in many ways distorted—by Indian media narratives.

Meeting him completely changed that. He invited me to Sri Lanka, and I visited for the first time in 2003. It was truly love at first sight. I was struck by how familiar parts of the southern regions felt—very much like Kerala. I was moved by the warmth of the people, their courtesy, their warm and genuine smile, and the ease with which they welcomed strangers.

I loved the food, the historical sites, and the overall atmosphere of the country. I still remember landing from Tiruchirapalli at Katunayake—seeing the ocean and the palm trees from the air and thinking, this really is paradise.

Since then, I’ve been visiting Sri Lanka almost every year—except in 2020, for obvious reasons. That friend I met years ago has since become like an elder brother to me; I’ve watched his children grow up. Through him, the country opened itself to me, and over time, I travelled extensively across Sri Lanka.

Now each time I have to leave Sri Lanka, I genuinely feel a sense of sadness—almost like leaving home for a foreign country. Sometimes I even feel I was born on the wrong side of the Palk Strait. It’s a place I deeply identify with and love. I have friends across communities, including a close friend in Jaffna whose wedding I attended.

Over the years, I’ve travelled widely across the island and often like to welcome the New Year in Sri Lanka. I’m comfortable in Tamil and have also made an effort to learn Sinhala. For someone from this part of India, it isn’t particularly difficult—there are many shared words and similar sentence structures. Sinhala, Marathi, and Hindi overlap in interesting ways.

Colombo, in particular, holds a special place in my heart. When I first visited in 2003, many of the old bungalows were still standing, and the city reminded me strongly of Bombay in the 1950s. In fact, when the film Bombay Velvet—set in that era—was made, the director chose to shoot in Colombo because it resembled old Bombay more than Bombay itself does today.

My interest in history draws me to Colombo’s fading heritage—the Port, Fort, Pettah, and surrounding areas. That heritage also survives in the way English is spoken there, with a certain elegance and grace. I remember an immigration officer at Katunayake once telling me, “You may proceed,” instead of simply saying “go.” That small detail stayed with me.

Amid the rise of glass towers and skyscrapers, Colombo still feels like a place where living history coexists with the present. That sense of continuity—of stepping into the past while standing in the present—is what I love most about the city, and about Sri Lanka as a whole.

When did you decide to write about Colombo: Port of Call?

There’s actually a story behind that decision. Interestingly, my earlier books—although they are about Russia—were written in Sri Lanka. I find Sri Lanka to be a place of great peace and quiet for writing. At some point, my friends there began joking with me, saying, “You keep coming here and writing books about Russia. When are you going to write a book about us?” And I realised they had a point.

The idea really began to take shape after I wrote an article about the old Boat Mail, which I mentioned earlier. Articles I wrote about Sri Lanka for Scroll and On Manorama were consistently widely read, which made me think it was perhaps time to commit to a larger project.

The idea for the book crystallised toward the end of 2023. I discussed it with my literary agent and told him that Colombo was historically one of the great ports of the world. It was a key stop on what was once called the East–West Highway, stretching from places like Yokohama or Shanghai, across the Indian Ocean and through the Suez Canal. So many famous travellers had passed through Colombo, and many had written about what they saw.

What fascinated me was this question: these travellers saw many of the same places we see today—but how did they look then? What impressions did these visitors carry back with them? That’s where the idea really germinated.

I then spent an extended period in Colombo researching the book. I met historians, visited archives, and retraced the paths of these travellers. I went to the places they had written about to see how they look today. For instance, if you go to the Galle Face Hotel, there’s a Traveller’s Bar with photographs of famous guests who stayed there. I would read their accounts and then walk those same spaces.

In some cases, the travellers themselves didn’t leave detailed writings, so I had to rely on the accounts of companions or co-travellers. Take the example of Japan’s Crown Prince Hirohito, who later became emperor. He visited Colombo and Kandy during a highly secretive tour, just a few years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Much of the reporting on his visit appeared only after he had left the island. In his case, I relied on the writings of a co-traveller who documented what he did while in Sri Lanka.

Similarly, when Mahatma Gandhi visited Sri Lanka, one of his companions wrote extensively about the journey. Gandhi arrived in Colombo by ship from Bombay but departed from the north. He held public meetings, met local leaders, and figures such as Lady Ramanathan played an active role in supporting his causes, including fundraising for the Satyagraha and the promotion of spinning and swadeshi. Many of these details are not widely remembered today, even in Sri Lanka.

The aim of the book was to uncover these forgotten anecdotes—where these visitors went, whom they met, what they felt, and how they interpreted what they saw. Because I’ve been fortunate enough to visit many of these places myself, I could compare their impressions with how those spaces look and feel today.

Writing the book also forced me to rethink how we engage with colonial-era heritage. It’s easy to admire beautiful colonial architecture or sit in places like the Grand Oriental Hotel, the Galle Face Hotel, or Mount Lavinia and romanticise the “good old days.” But those were not the good old days for people like you and me. They were the good old days for colonial elites—not for the colonised population.

When you read these travel accounts, you see both admiration and prejudice. Some figures—like Don Bradman or Mahatma Gandhi—wrote with deep respect and affection for the people they encountered. Others, such as Mark Twain, expressed genuine fascination with everyday life in Colombo. But there are also descriptions that would be considered deeply offensive today.

What becomes clear from the archives is that colonial Colombo was a place where Europeans and Westerners could live in great comfort, while the local population occupied a distinctly second-class position. Acknowledging this means looking at the past with honesty.

What has remained constant, however, is the island’s natural beauty. The descriptions of Sri Lanka’s landscapes in these old accounts make for delightful reading.

At the same time, these travelogues also reveal a great deal about the travellers themselves. How someone describes a place often tells you more about their worldview than about the place itself. Some visitors described Kandy as the Garden of Eden. Others were far less impressed. One Belgian traveller, Jules Leclercq—who wrote in French, which I translated—visited the Temple of the Tooth Relic and felt deeply disappointed. He compared it unfavourably with the great temples of Madurai, Konark, and Jagannath, calling it too plain.

Those contrasts are fascinating because through them, you begin to understand not just Colombo or Sri Lanka, but the minds of the people who passed through it. That, ultimately, is what Colombo: Port of Call tries to capture.

Could you explain to our readers how significant Sri Lanka—especially the Port of Colombo—was in historical terms?

Colombo was an extremely important port—one of the most significant in the world during the age of sea travel. To begin with, for ships travelling from Britain to Australia, Colombo was the last major port of call before reaching Fremantle in Western Australia. Travellers often wrote about how, after leaving Colombo, there was nothing but open ocean for days, which many found rather depressing.

Because of this, Colombo became a crucial place to restock—coal, supplies, and commodities. Sri Lanka exported rubber, tea, and, earlier, coffee. In fact, coffee was once the island’s primary export until the industry collapsed due to a fungal disease, after which tea took its place.

Colombo’s importance also lay in its position on what was once called the East–West Highway. Ships from Europe would cross the Suez Canal, stop at Aden, then head to Colombo before continuing to China, Japan, and East Asia. Almost every long-distance sea journey to Australia or East Asia involved a stop in Colombo. Some ships stayed for several days; others at least paused for 20 to 24 hours.

This constant flow of travellers had cultural consequences as well. Sri Lanka’s love for cricket, for example, is closely linked to this maritime history. Don Bradman visited Colombo several times and played cricket there—remarkably, it is the only place in South Asia where he played. Teams travelling by ship from Australia to England for the Ashes had little to do onboard beyond swimming and deck tennis, so when they reached Colombo, they often played one-day matches in a Test format. Bradman played there before he became a global superstar and again on later visits.

The port’s importance was not only logistical but also cultural and touristic. Famous travellers such as Mark Twain passed through Colombo as part of his global tour, Following the Equator. Russian Crown Prince Nicholas—later Tsar Nicholas II—also visited Colombo during his journey from European Russia to Vladivostok, travelling by sea after crossing India. These visits were widely reported in newspapers, which helped popularise Colombo as a tourist destination.

Writers and travellers across the world described Sri Lanka in almost mythical terms. Anton Chekhov famously referred to it as “Paradise on Earth.” Such accounts had a powerful impact, making Colombo one of the most desirable stops on a global journey.

Until the rise of air travel, Colombo was arguably the most important port in South Asia. It also served as a gateway to southern India. Railway guides published by the Southern Indian Railways actually advised travellers to enter India via Colombo. At the time, rail connectivity between Bombay and southern India was poor—the Konkan Railway, for instance, was only completed in the 1990s. So travellers were encouraged to sail to Colombo, take the Boat Mail to India, and then explore the southern regions.

In that sense, Colombo was not just a port—it was a hub. A hub for global trade, tourism, culture, and movement. Anyone travelling between Europe, East Asia, Australia, and southern India passed through Colombo. From the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, it was one of those cities that ambitious travellers, writers, and thinkers felt compelled to visit.

Do you believe the Boat Mail service could be revived in the near future—or at some point in the future?

I would absolutely love for that to happen. Unfortunately, the reality is that such initiatives are often entangled in internal politics—particularly in Tamil Nadu. Historically, whenever there has been a need to divert attention from local issues in Tamil Nadu, Sri Lanka has sometimes been used as a convenient political bogeyman.

That said, I do see progress. The ferry service from Nagapattinam to Kankesanthurai is a positive step forward. Even limited services like this matter, because they signal intent. But we need much more than that. Ideally, ferry services between Rameswaram and Talaimannar should also be revived.

If that happens, it would be transformative for regional integration. At one point in history, you could buy a railway ticket in Colombo—either at Fort Station or through official channels—and travel to virtually any destination on the Indian Railways network. That system existed, and I genuinely believe we should actively explore restoring something similar.

Such a service would not only be nostalgic or symbolic; it would be immensely practical. For people with family ties across the Palk Strait—especially those from less affluent backgrounds—it would be a real boon. Air travel is expensive, and surface transport offers a far more accessible alternative.

Personally, I would be among the first to take the Boat Mail if it were revived. I should add that the India leg of the train still exists and terminates at Rameshwaram.

If the full service to Colombo was restored, I’d happily go to Egmore, passport in hand, board the train, and enjoy the journey. Historically, many travellers didn’t simply rush straight to Rameswaram. They stopped along the way—visited Madurai, for instance, to see the Meenakshi Amman Temple—because travel itself was part of the experience. I would gladly do the same: explore Tamil Nadu’s great temples, cross the Palk Strait, spend time in Talaimannar, and then continue onward.

We have to acknowledge that there are both genuine and imagined fears around deeper integration. Sri Lanka is a country of just over 20 million people, while India is a subcontinent of 1.4 billion. Sri Lankans value their national identity and sovereignty—and rightly so.

Given the global climate today, where we hear unsettling rhetoric about territorial expansion in other parts of the world, it’s important to be sensitive to these concerns. In that context, reviving a historic, people-to-people transport link like the boat mail feels far more organic, less threatening, and more respectful of sovereignty.

What is your personal view on the proposal to connect Talaimannar and Rameswaram through a bridge?

Honestly, I think integration of this kind is a good idea. If you look at global examples, there are successful precedents. Take the bridge connecting Hong Kong, Zhuhai, and Macau—it’s an extraordinary engineering achievement and has significantly improved connectivity and travel within the region.

A bridge between Talaimannar and Rameswaram could bring similar benefits. It would greatly help people who have family connections on both sides of the Palk Strait and would also enhance trade and economic exchange. From that perspective, I genuinely believe it is a positive idea.

In fact, I think Sri Lanka would stand to benefit even more than India. Greater connectivity would give Sri Lankan businesses easier access to a vast market. We already see this in aviation—SriLankan Airlines benefits enormously from its strong India-facing network, with Colombo serving as a major transit hub for Indian passengers. Deeper economic integration would likely amplify these kinds of advantages.

I don’t personally subscribe to many of the fears that are often raised—about sovereignty or loss of identity. I feel these concerns are frequently exaggerated. If managed sensibly and with mutual respect, such a project could benefit both countries.

Do you plan to write about other Sri Lankan cities as well—such as Jaffna or Batticaloa? They, too, have very interesting stories.

They absolutely do have fascinating stories. The only reason I haven’t written more about those cities yet is that I haven’t spent enough time there. If I ever get the opportunity to spend a longer period in Jaffna, I would love that.

There’s a wonderful feeling about Jaffna—I genuinely feel like a local when I’m there. And the sunsets are extraordinary. The twilight, especially, is hard to describe—the colours are simply incredible. I love walking around the Fort area, and I really enjoy just being in the city.

Jaffna has a deeply fascinating history. I’ve already written one article about how the Dutch once sought to develop Jaffna into a major trading hub while they controlled parts of the island. That alone opens up so many possibilities for deeper exploration.

If I were to write more about Jaffna, I would focus on its historical links with Tamil Nadu and Kerala, but also on its lesser-known international connections, which are surprisingly strong and largely forgotten today. It’s a story waiting to be told, and I would genuinely love to work on it.

You have written extensively about Russia, and many feel you were among the few writers who helped change Indian perceptions of the Soviet Union and Russia. How did your interest in Russia begin? Did it start around the end of the Cold War?

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, I was 12, living in New York. In the United States, this was celebrated as a great victory—America had “won” the Cold War. Growing up there, I was constantly exposed to the idea that America stood for liberty, justice, and freedom, while the Soviet Union represented everything that was supposedly wrong with the world. When you hear that narrative 24/7 as a child, you tend to believe it.

I was told all kinds of absurd things—for example, that Soviet authorities fed dissidents to sharks. When I later repeated this story to people in Russia, they laughed and said, “Of course we did—once we found sharks in our sea.”

When I moved back to India at the age of fourteen, I encountered a completely different narrative. People here said, “No, Russia is our friend. They were always on our side.” At first, I resisted that idea because my worldview had already been shaped by American media. But hearing a different perspective made me curious. I decided to start learning the Russian language.

Until then, I had basically lived only in two major cities—Bombay and New York. I wanted something different: less crowded, closer to nature. In 2003, I moved to the Russian Far East, initially with the idea of travelling across Siberia, visiting places like Kamchatka, and experiencing the world’s largest country by landmass.

I ended up falling in love with the country. I learned the language properly, stayed on, and lived there for years. Russia shaped me in profound ways and played a major role in making me who I am today.

As a writer, I felt it was important to share a perspective on Russia that Indian readers rarely encountered. I wanted people to see the country beyond the stereotypes—beyond the narratives pushed by many Western media outlets. Russia and India share deep historical ties, especially dating back to the Soviet period, and those connections deserve honest exploration.

Of course, every experience is subjective. Just as someone might visit Jaffna and have an experience different from mine—yet equally valid—I was sharing my Russia, based on lived experience. My goal was never propaganda; it was perspective.

Only in recent years have I begun travelling more extensively through former Soviet republics—Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Belarus, and Ukraine, which I visited before the war escalated in 2022. These regions are rich in history, culture, and stories that are still largely unknown to Indian readers. I want to write more about them and encourage people to visit, because travel builds bridges in ways politics never can.

When people travel, meet each other, and form friendships, it becomes much harder to manipulate them through media narratives. In the 1990s, it was easy to convince people that entire nations hated each other. Today, that’s far more difficult. If someone tells you the average Sri Lankan hates Indians, most people will simply laugh—because there are multiple daily flights, family connections, friendships, and lived experiences that contradict such claims.

I also strongly believe that Indians should read more work by Sri Lankan writers and journalists, and vice versa, without Western filters and bias. This is not a blanket criticism of Western writers, many of whom are excellent, but in this day and age, we should not let the ‘divide and rule’ principle prevail.

In addition, we need to move beyond tribal instincts and recognise our shared humanity. Too often, conflicts are fuelled by people who don’t live here, don’t understand us, and benefit from division. The former Soviet space, much like South Asia, has become a battleground for competing ideologies. One way to resist that is through writing, travel, and genuine cultural exchange.

That’s why I value local publications so deeply. I would rather read a nuanced account of Jaffna written by Jaffna Monitor than a parachute journalist flown in from the West with a predetermined narrative.

If we want less conflict and more understanding, this is where we should start: listening to each other, writing honestly, travelling widely, and refusing to let others define us for one another.