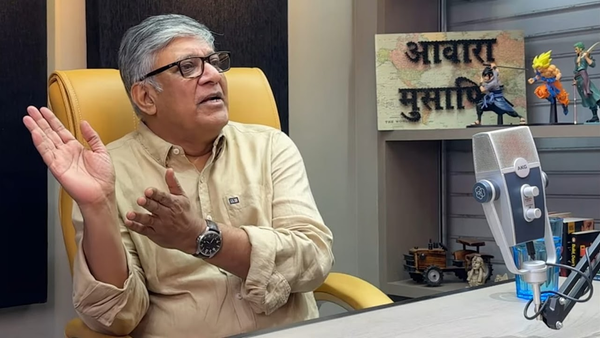

The teleseries The Hunt: The Rajiv Gandhi Assassination Case has emerged as both a cultural flashpoint and a streaming triumph — celebrated by many and debated with particular fervour within Sri Lankan circles and the global Tamil diaspora. At the heart of this narrative stands the man whose original work inspired the series: Anirudhya Mitra, author of the bestselling 90 Days: The True Story of the Hunt for Rajiv Gandhi’s Assassins. A gripping account of India’s most high-stakes manhunt, 90 Days has been adapted into the acclaimed SonyLIV web series The Hunt, directed by National Award-winner Nagesh Kukunoor and produced by Applause Entertainment.

An accomplished author, screenwriter, and producer with over three decades of experience, Mitra’s career spans print, television, film, and digital platforms. Before entering the world of screenwriting and production, he spent a decade as a Special Correspondent with The Times of India and India Today, breaking some of the most consequential stories of his time — from the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi and the labyrinthine Bofors scandal to the Pamella Bordes affair, the controversial godman Chandraswamy, and the BCCI bank scam, where his investigative reporting on money laundering played a pivotal role in the global fallout that led to the bank’s closure.

Anirudhya Mitra’s creative range is formidable. He created and produced Sea Hawks (1996–99) — India’s No. 1 action series for DD Metro under the UTV banner — featuring Om Puri, Madhavan, Niki Aneja, and Milind Soman. Based on the Indian Coast Guard, it became a national phenomenon, unmatched in scale and ambition within Indian scripted action television. His years in Indonesia saw him co-produce several landmark films, including Habibie & Ainun (Indonesia’s highest-grossing film), Merry Riana, and Di Bawah Lindungan Ka'bah (Indonesia’s official entry for the 2012 Oscars).

Currently based in Mumbai, Mitra heads a team of writers developing original content for FreshLime Films, Banijay Asia, and Amazon, with projects in collaboration with Netflix, Ajay Devgan Films (ADF), and Fortune Films.

In a rare and expansive interview with Jaffna Monitor, Mitra reflects on the high-stakes investigations that defined his career, the moral and strategic missteps that sealed the LTTE’s fate, and the vanishing patience required for journalism that seeks not just to inform, but to endure.

During your tenure with major Indian newspapers (The Times of India and India Today), you were responsible for breaking several significant stories. Could you walk us through your evolution as an investigative journalist during this pivotal and transformative period in Indian journalism?

I was a journalist in what I often call the analog era—from 1981 to 1993—before I made the leap into scripted television. It was a different world then. You took hurried notes on a pad or discreetly used a pocket-sized recorder if you were lucky. I started with a typewriter—tap-tap-ding—and graduated to computers where, for the first time, you could write and edit without wasting sheets of paper. That transition itself was symbolic of how journalism was evolving.

The term “investigative journalism” had already acquired a sort of mythic stature post-Watergate. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were our rock stars. In India, we looked up to names like M.J. Akbar, Shekhar Gupta, and Arun Shourie—journalists who weren’t just reporting stories, they were uncovering scathing, uncomfortable truths.

From the beginning, I was drawn towards investigative work. While many colleagues enjoyed the adrenaline of political beats or the daily churn of press conferences, I found my calling in digging deeper into crime, white-collar fraud, economic offences. My early years at The Times of India were all about building those muscles and learning how to sniff out a lead, build sources, and, most importantly, earn trust.

But it was at India Today that I truly flourished. Their editorial culture encouraged deep-dive investigations. They backed you with logistics, time, and trust. That support allowed me to pursue complex stories that needed patience, perseverance, and occasionally, a bit of audacity.

Those years taught me that good investigative journalism isn’t about chasing headlines—it’s about chasing the truth, even when it’s inconvenient, unpopular, or buried under a hundred locked doors.

You played a key role in the follow-up investigations into the Bofors scandal. What was it like, as a journalist, to pursue a story that directly implicated the sitting Prime Minister? And how did you navigate the political pressures that came with such high-stakes reporting?

It was thrilling, no doubt. But it was also risky—emotionally, professionally, and politically. Risky not in the sense of being followed or threatened, but in the sense that every word you wrote could become a landmine. You had to be surgically precise with facts. There was no room for error.

Bofors wasn’t just a financial scandal, it was a political fireball. The story wasn’t driven by investigators in uniform, but by whispers from the corridors of power. Most of our leads came not from enforcement agencies, but from political insiders—people with their own agendas, factions within the ruling party, disgruntled allies. It made the story murkier but also more alive. You were constantly decoding who was leaking what, and—very importantly—why.

Every rebuttal from the government had to be countered point by point, backed by documentary evidence, airtight sourcing, and clean copy. There was no room for innuendo. Political pressure existed, yes — but often, the greater pressure came from within the newsroom. Some senior editors were more loyal to power than to the truth, and a few worked overtime to shield the Prime Minister’s image. Navigating that required a different skill set altogether: diplomacy, patience, and, at times, simply outworking everyone else.

What kept the investigation alive was a simple principle: consistency. Keep surfacing new facts, new documents, new leads — and a piece of truth becomes impossible to ignore. That was our method. That, and never betraying a source who trusted you with their neck.

Your reports on the Sri Lankan conflict made a significant impact. How did this chapter first enter your professional world?

My brush with that chapter of history came in the aftermath of the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi. I had just joined India Today magazine, and within weeks, I was dispatched to Madras (now Chennai) to cover the investigation led by the CBI’s SIT. That’s when Sri Lanka, the IPKF, and the Tamil Tigers entered my professional universe. I wasn’t on the ground with the IPKF, but I was very much on the trail of the story that grew out of it—and changed the course of Indian politics forever.

Did you have any direct interactions with LTTE members or commanders? If so, what impressions did they leave on you—ideologically or operationally?

I never reported from Sri Lanka directly. After breaking my first major story for India Today, “The Inside Story of Rajiv Gandhi’s Assassination,” I was keen to travel to Sri Lanka and understand the LTTE movement at its root. But the Sri Lankan authorities denied me a visa, citing security concerns. Shortly after, in a media interview to a Western outlet, LTTE supremo V. Prabhakaran himself spoke about me, unflatteringly, I might add. That sealed the matter. My editors, and more importantly, my family, urged me to drop the idea of going.

But even without setting foot on Sri Lankan soil, I wasn’t entirely out of the LTTE’s radar. While reporting from Madras in 1991–92, during the thick of the CBI-SIT investigation, some LTTE sympathizers and operatives did reach out carefully and discreetly. It was never a formal interaction, but enough to understand that they were deeply ideological and fiercely committed to their cause.

I didn’t see it in black and white. I understood they were fighting for what they believed to be justice for their people. I had no personal animosity toward that so long as it didn’t threaten the integrity or security of my own country. At the same time, I was equally critical of many aspects of my own government’s handling of the Sri Lankan crisis. As a journalist, my job wasn’t to choose sides, but to understand motivations and reveal the truth, no matter how inconvenient it was to either side. It was an open secret that some in CBI weren’t happy with my coverage at all.

In hindsight, how do you assess India’s intervention in Sri Lanka through the deployment of the IPKF?

India’s intervention in Sri Lanka through the IPKF was well-intentioned but deeply complicated. On paper, it was about peacekeeping, protecting civilians, disarming militants, and stabilizing a neighbor in crisis. But on the ground, things rarely follow the script. The Indian troops walked into a situation far more layered than what Delhi had imagined, and they ended up fighting the very group they were initially meant to oversee – the LTTE.

It taught us many things. First, military boots can’t fix political problems unless there is absolute clarity on mission, mandate, and exit. Second, even with the best intentions, you lose legitimacy the moment civilians begin to suffer. There were allegations of excesses by the IPKF, and those scars never fully healed. It was a classic case of a mission outpacing its brief, with goodwill turning into resentment on both sides.

From a journalist’s point of view, the IPKF years are a reminder that regional power doesn’t automatically translate to regional acceptance. And that intervention, however noble it may sound in diplomatic corridors, must always be tempered with humility, realism, and deep cultural understanding.

Looking back, I remain critical of violence, no matter who uses it or why. Whether it came from the state, the rebels, or anyone else, it only pushed people further apart. The biggest lesson, perhaps, is that peace can’t be dropped from a helicopter or an ivory tower. It has to be built from within.

While many continue to believe that the convicts in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case—such as Nalini, Perarivalan, and a few others—were unaware of the sinister plot to kill the former Indian Prime Minister, your book suggests otherwise. You indicate that they had prior knowledge of the attack. Could you please elaborate on the basis for this conclusion and the evidence that led you to that assessment?

I’ve never subscribed to the theory that Nalini was unaware of the plot to kill Rajiv Gandhi. She was far too intelligent and self-aware to be completely in the dark. I had the chance to observe her closely, whether during court production or in police custody, and I did ask her, point-blank: why did she join the celebration in Tirupati after the assassination? And more importantly, why did she go on to marry Murugan, one of the key conspirators? For reasons best known to her, Nalini thought my questions were not worthy of her reply.

Even if, for argument’s sake, we accept that she didn’t know Dhanu was armed with explosives, that ignorance couldn’t have lasted beyond the moment of the blast. She was right there. She witnessed the assassination. And yet, she continued to remain with the core group. You could say she was under pressure or fearful, but nothing in her demeanor suggested that. Her defiance, the sharpness with which she countered investigators during interrogation – well, it wasn’t the posture of someone broken or manipulated.

Your book gives a heart wrenching account of the cyanide deaths in Sivarasan’s hideout. Do you believe those assassins acted autonomously at that moment, or was there coordination or instruction from LTTE command on how to respond if cornered?

I believe the moment an LTTE cadre wore a cyanide capsule around their neck, they had already made peace with how their story might end. It wasn’t just a tool of last resort; it was part of their identity. That understanding didn’t need to be reinforced in real time. It was ingrained.

As for whether there was any communication between Jaffna and Sivarasan’s hideout in Konanakunte in those final moments, I can neither confirm nor deny. But realistically, it seems improbable. The net was closing in. The area was surrounded. Any communication between him and Jaffna was highly unlikely.

You humanize characters like Nalini and Perarivalan without justifying their actions. What was your process in balancing empathy with accountability, and did any personal stories profoundly change your perspective?

I’m not sure if I fully grasp what the question is aiming at, but I’ll say this: I never saw Nalini, Perarivalan, or others involved as my enemies. They weren’t born to kill. They were shaped, manipulated, and in some ways, consumed by an ideology that preyed on their vulnerabilities – their youth, their circumstances, socio-economic in particular, and their need to belong to something larger than themselves.

That said, empathy doesn’t mean exoneration. My job was never to judge or to forgive. It was to observe, report, and let the truth speak for itself. I was a journalist and not an activist, not a campaigner. What mattered most to me then was telling the story with as much accuracy, depth, and integrity as possible.

In the web series The Hunt, it's suggested that Sivarasan may have been planning to target other politicians following Rajiv Gandhi's assassination, with Jayalalithaa mentioned as a potential next target. Based on your research, do you believe such a plan existed, and if so, what evidence supports this?

I thought it was already there in my book! I had reported this back in the day for India Today. The idea that Rajiv Gandhi was the only target simply doesn’t hold. According to investigators, Sivarasan had a broader hit list, which included the then Tamil Nadu Congress chief Vazhapadhi Ramamurthy, DGP S. Sripal, and the SIT chief D.R. Karthikeyan.

These weren’t just speculative theories whispered in police circles; evidence was presented before the court, and the SIT stood by it. My reporting was grounded in those official findings, not conjecture. Whether all those plans would have materialized, we’ll never know. But the intent, as established by investigators, didn’t look unreal.

If the LTTE did consider targeting Jayalalithaa, it raises a puzzling question: why would Prabhakaran target someone who embodied the political legacy of M.G. Ramachandran—one of his most admired figures and a key LTTE benefactor? Do you believe this idea might have been influenced by certain Tamil Nadu political actors with close LTTE ties, particularly given M. Karunanidhi's serious allegation that Vaiko conspired with the LTTE to assassinate him after his 1993 DMK expulsion?

See, according to investigators at the time, there was a very real concern that Jayalalithaa might be on the LTTE’s radar, largely due to her fierce political rivalry with the DMK and M. Karunanidhi. The LTTE’s relationship with the DMK was well-known, and by that logic, they could not have expected anything but hostility from the AIADMK government under her leadership. Mr. Karthikeyaan once claimed that he was asked to arrest Karunanidhi, which he politely declined for lack of evidence.

As for M.G. Ramachandran being a revered figure for Prabhakaran, possibly, but nostalgia rarely trumps cold, strategic thinking in politics or armed movements. After all, the LTTE had reportedly received training from Indian agencies during Indira Gandhi’s tenure. Yet, that didn’t stop them from masterminding the assassination of her son. Allegiances shift. Equations evolve. There are no permanent friends or enemies in politics.

Now, as for Karunanidhi’s allegation about Vaiko conspiring with the LTTE post his DMK expulsion in 1993, it was a serious charge. But I’d refrain from speculating on the internal politics of Tamil Nadu beyond what was established by investigators.

Some former LTTE cadres who have since rehabilitated and now live in Sri Lanka maintain that the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi was not a centrally sanctioned LTTE operation, but rather the act of a few individuals within the organization who were personally affected by the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF). Notably, there have been persistent claims that the suicide bomber, Dhanu, was a victim of sexual violence by the IPKF. Based on your research and investigative reporting, do you find any merit in these accounts—or do you view them as speculative or unfounded narratives?

I find those claims largely unfounded. The LTTE was not a loosely structured outfit where individuals could act independently on a mission of such scale and consequence. Anyone who understood how the organization functioned under Prabhakaran would agree that nothing of this magnitude could have been executed without his direct sanction. His control over the cadre was absolute.

As for the story of Dhanu being a victim of sexual violence by the IPKF, I’ve come across that claim. But in all my years of reporting and research, I haven’t found credible evidence to support it. That said, I do understand that trauma, grievance, and rage fuel many insurgent movements. But in this case, the assassination of a former Prime Minister could not be the work of a few rogue elements in my opinion.

The Jain Commission's final report highlighted what Justice Jain called a 'CIA-Mossad-LTTE link' and concluded there was evidence of 'an international plot,' though it acknowledged significant 'gaps and missing links in evidence.' What is your assessment of these foreign conspiracy allegations? Did you encounter any leads during your reporting that suggested international involvement beyond the LTTE acting independently?

Yes, these theories did surface, and some leads were certainly explored; especially after Yasser Arafat reportedly conveyed concerns to New Delhi about an international dimension to the plot. But beyond those whispers, nothing concrete ever emerged. In my own reporting, I came across hints, half-claims, and off-the-record musings, but never anything that could be a verifiable fact.

In hindsight, the recovery of the photographic film from Hari Babu’s camera—capturing the moments leading up to the assassination—proved to be a pivotal breakthrough in identifying the perpetrators. Do you believe that, had the LTTE not documented the attack and the film roll not been seized, Indian investigative agencies would still have been able to trace and identify the real assassins with the same level of clarity and speed? Or was this photographic evidence truly the turning point in the manhunt?

No doubt, the recovery of Hari Babu’s film roll was a crucial breakthrough. It was, in many ways, the silent whistleblower of the case. Those photographs didn’t just capture the last moments before the blast; they gave faces to the shadows. But that said, I do believe that a committed investigative team - like the one led by the SIT - would have eventually cracked the case. It may have taken longer, it may have followed a more winding path, but they had the tenacity, the resources, and above all, the clarity of purpose to get to the truth. It happens anywhere in the world.

Were there any materials—such as testimonies, documents, or leads—that you came across during your investigation but chose not to include in the book due to legal, ethical, or national security considerations? If you’re comfortable, could you share any insights about those omissions?

I’m sure there were materials like testimonies, leads, maybe even documents that we came across but didn’t pursue or include. It’s been over three decades, and honestly, much of what didn’t make it to print back then was either discarded for lack of clarity or relevance. We were working in real time, chasing deadlines you know.

If anything, truly explosive had come my way and passed the basic smell test, it would’ve found its way into my book. I didn’t hold back on anything I felt the public had a right to know. But yes, it’s entirely possible that in the noise of those times, something slipped through.

How closely were you involved in the creative process of adapting 90 DAYS into the SonyLIV series, The Hunt?

I wasn’t involved in the creative process at all, beyond providing the makers with my book and some additional background material when they asked for it. The Hunt was their interpretation of 90 DAYS, shaped by their vision of how the story should be told on screen.

That said, adapting real events into dramatized storytelling is never easy. You’re walking a tightrope between fact and fiction; you are trying to stay true to the spirit of the story while making it work for a visual medium.

Timelines get compressed, characters get merged, and certain liberties are taken for narrative impact. So, while I kept a respectful distance, I was always curious to see how they would translate something so layered, so real, into a gripping series for today’s audience.

Given the inherent tension between investigative journalism and cinematic storytelling, how do you feel the series navigated the balance between factual accuracy and dramatic representation?

The Hunt is, in my view, a remarkable example of how to strike the right balance between factual integrity and creative liberty. It stays grounded in truth while using cinematic tools to enhance and not distort the storytelling. My book is consciously apolitical, and so is the series. That’s a rare alignment, and one I deeply appreciate.

At no point, while watching The Hunt, did I feel the narrative was overly dramatized or sensationalized for effect. The tension, the urgency, the emotional undercurrents - they were already embedded in the real events. The creators didn’t need to manufacture drama; they simply presented it with intelligence and restraint.

Sivarasan, in particular, has always been an enigma - then and now. And yet, the way he’s portrayed in the series is more than just accurate - it’s layered, chilling, and entirely believable. For a story that has haunted the country for decades, I think The Hunt did justice to both the facts and the emotions behind them.

Given that Prabhakaran had successfully waged guerrilla war against the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) and demonstrated considerable tactical acumen, do you believe he was politically naive enough to think he could authorize or allow the assassination of the grandson of India's first Prime Minister and still escape the consequences?

That’s a difficult one to answer definitively, especially since my deep dive into Prabhakaran was more from an investigative lens than a political or psychological one. But if history has taught us anything about guerrilla leaders, it’s that their tactical brilliance often walks hand-in-hand with political miscalculations.

Prabhakaran had beaten back the IPKF and outmaneuvered conventional forces, no doubt. But ordering or even allowing the assassination of the grandson of India’s first Prime Minister was a decision perhaps far beyond battlefield logic. If he thought he could carry out such an act and still maintain political space or diplomatic sympathy, then yes, perhaps he underestimated the consequences.

In the short term, he may have believed it was a strategic strike. But in the long run, it proved to be a fatal misstep. His movement lost whatever moral high ground it once claimed, and eventually, the space for negotiation and survival shrank to zero.

In my view, the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi marked the first nail in the LTTE’s coffin. From your perspective, how did the LTTE’s international and regional standing shift in the aftermath of this assassination?

The assassination of Rajiv Gandhi marked a watershed moment for the LTTE; indeed, the first nail in their coffin. Before 1991, the organization enjoyed significant sympathy and operational freedom, especially within Tamil Nadu. But the killing shattered that goodwill overnight. Within weeks, public sentiment in India turned sharply against them; their political and logistical networks in Tamil Nadu were dismantled over the coming months.

Diplomatically, the LTTE lost ground too. India officially proscribed them in 1992, followed by many Western nations in the 2000s. What had once been seen by some as a liberation movement became instead a globally reviled terrorist entity, and the group gradually found itself isolated in international forums.

By the time the Sri Lankan military launched major offensives in the east (2006) and north (2008– 2009), the LTTE had lost nearly all political leverage and external cover. Their military defeat at Mullivaikkal in 2009 was not only the end of their territorial control, but the culmination of the diplomatic and moral isolation that began with the 1991 assassination.

The book details several instances where intelligence warnings were either ignored or not acted upon effectively. In your view, what systemic changes in India's security architecture could have prevented not just this assassination, but the kind of intelligence failures that enabled it?

Intelligence agencies, across the world, are often remembered more for their failures than their silent successes. That’s the nature of their work - what they prevent stays invisible; what they miss becomes history. The assassination of Rajiv Gandhi by a foreign terror outfit on Indian soil was undoubtedly a massive intelligence lapse. It shook India’s security architecture to its core. Post that, there was a marked shift in how intelligence was followed up, how leads were treated, and how inter-agency coordination was prioritized.

That said, this wasn’t a simple miss. It was a series of missteps, misjudgments, and what some might even call destiny. My book goes into great detail about how Rajiv Gandhi was advised not to campaign in Tamil Nadu at all, especially with the Congress in a strong alliance with Jayalalithaa’s AIADMK. But he insisted on going to support his old family friend, Margatham Chandrasekhar, his so-called “aunty.” That one emotional decision rewrote history.

Even on the day of the assassination, there were moments when fate could have intervened. His aircraft developed a snag in Vizag, and he was on the verge of returning to Delhi. ‘Aunty will feel bad,’ he reportedly said, before boarding the flight once it was fixed. At the Sriperumbudur venue, a female police officer named Anasuya tried to keep Dhanu, along with Haribabu and Sivarasan, off the red carpet, as none of them had official clearance. But Dhanu was persistent, calm, and ultimately succeeded.

So yes, structurally, there were failures. But they were also intertwined with political compulsions, human emotion, and tragic coincidence. The lesson is clear: in matters of national security, instinct and protocol must always trump sentiment. Because sometimes, you don’t get a second chance.

What revelations about the assassination surprised you the most during your investigation?

What truly stunned me was discovering that the LTTE hit squad conducted a sort of “dry run” before the assassination, something deeply rooted in their operational culture. They didn’t just plan and execute; they rehearsed. They actually recorded a mock version of the assassination – visually - so they could later study the footage, analyze what worked, what didn’t, and fine-tune their approach. It was clinical, methodical, and terrifying in its precision.

How do you view the evolution of investigative journalism in today’s digital age? Do you think modern journalists are better equipped with technology and access to information, or have we lost something essential — such as institutional backing, deep source relationships, and the patience required for long-form investigations that often take months to develop?

Journalism today is faster, louder, and far more technology-driven than what we practiced back in the day. Journalists now have access to tools we couldn’t have dreamed of — databases, surveillance tech, open-source intelligence, social media footprints. Information is abundant. But truth? That still takes digging.

What we had — and what I fear is slowly fading — was time and institutional backing. We were allowed to chase a story for weeks, sometimes months. Editors backed us not just with logistics, but with trust. More importantly, we had real relationships with sources. We built them over tea or a glass of beer, over silence, over years. Today, much of that has been replaced by emails, leaks, and one-off quotes — often given in lieu of, or in expectation of, favors.

That said, I don’t believe in romanticizing the past too much. Each era brings its own strengths. But I do worry that in the rush to be the first to break, we’ve forgotten the value of being the one who gets it right. Long-form investigations require patience, obsession, and a stubborn refusal to settle for half-truths. That spirit still exists; it’s just harder to nurture in today’s newsroom economy.

So yes, the tools are sharper now. But the craft? That still depends on the journalist holding the pen or the camera.

For young journalists interested in investigative work, what practical advice would you offer based on your experiences? You mentioned working on your next book. Can you give us any hints about what story you're exploring now?

To begin with, what’s my next book - it’ll be out in the stands this September. It’s the authorized biography of one of the country’s most formidable top cops. An enforcer who took on gangsters, terrorists, and the rot within the system and did it without ever chasing the limelight. It’s a story of grit, integrity, and the quiet madness that often drives real change.

As for young journalists drawn to investigative work, here’s my two-penny advice: curiosity is your greatest weapon but discipline is your best ally. Don’t fall in love with theories. Fall in love with facts. Build your stories brick by brick. Learn to be patient. The real stories never walk up to you. Actually, they hide in phone records, old files, body language, and silences that nobody notices.

Also, protect your sources like they’re family. Relationships built on trust will take you deeper than Google ever can. And finally, don’t chase fame. Chase clarity. If you get the story right, the byline will take care of itself.