When I began my Family Medicine training in 2022 as a Registrar, I moved between clinics, hospital wards, community camps, and even patients’ homes. These journeys gave me a front-row seat to the deep inequalities within Sri Lanka’s healthcare system—nowhere more visible than in stroke care.

In the government sector, stroke treatment is still woefully inadequate. Time is critical in managing stroke, yet delays in diagnosis and intervention are far too common. I’ve watched stroke survivors—many elderly—wait for hours, slumped in discomfort, without even a proper chair or wheelchair in sight. Others arrive in private three-wheelers, clutching onto hope and spending their last few rupees to make it to a brief physiotherapy session—only to find it cancelled due to a strike or sudden staff shortage.

In contrast, those who can afford it turn to private options—home nursing, personal physiotherapy, or doctor visits—often at considerable cost. But what truly stood out to me was what I witnessed in Jaffna: a completely different model.

There, it isn’t private providers but government health workers—nurses, physiotherapists, and doctors—who bring care directly to patients’ doorsteps. Through a coordinated, home-based stroke rehabilitation program, they offer more than just medical treatment—they restore dignity and hope to those who might otherwise be left behind.

Northern Sri Lanka’s Stroke Burden Doubles National Rate

Medically, a stroke occurs when the blood supply to part of the brain is suddenly cut off—either by a blockage (ischemic stroke) or bleeding (hemorrhagic stroke). It strikes without warning—like a bolt of lightning out of a clear sky—mercilessly robbing individuals of their ability to move, speak, or care for themselves. For many, it leaves behind a devastating trail of physical disability, psychological trauma, and crushing financial burden.

The prevalence of stroke in Sri Lanka’s Northern Province is significantly higher than the national average: 23 out of every 100,000 people (2.3%) suffer from stroke, compared to just 10 per 100,000 (1.0%) nationally. This stark difference underscores a disproportionate burden in this post-conflict region.

Stroke Begins in Seconds—But So Does Recovery

Time is brain. A clot or bleed in the brain begins killing neurons within seconds. Modern treatments—such as intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy—can reverse the damage, but only if administered quickly. These interventions require rapid diagnosis through CT scans, emergency transport, and skilled specialists—resources that are often scarce in rural or post-conflict regions like Northern Sri Lanka.

Yet hope is not lost.

At a recent global forum on stroke care held in Jaffna, neurologists and public health experts from across Asia delivered a unified message: stroke care must reach the people—rather than waiting for people to reach care.

Professor Jeyaraj Pandian, a leading figure in global stroke medicine, emphasized the need for comprehensive, continuous care—beginning with emergency response, progressing through hospital-based treatment, and continuing into long-term rehabilitation at home.

Recovery Doesn’t End at Discharge

One of the most critical but overlooked phases of stroke care is what comes after the hospital stay. For many survivors, the hardest part begins when they go home.

“Rehabilitation must begin within 24 to 48 hours after a stroke,” says Prof. Dorcas Gandhi. Early mobilization—getting patients out of bed, engaged in task-specific therapy—can significantly improve long-term outcomes. But in Low- and Middle-Income Countries, rehabilitation is often fragmented or missing altogether. There are too few physiotherapists, little home support, and even less access to speech or cognitive therapy.

In Innovation, There is Opportunity

This gap has forced many countries to rethink stroke care models from the ground up. Among the most promising solutions is community-based rehabilitation, powered by task-shifting.

What does this mean? It means training community health workers—people from the villages and towns themselves—to deliver basic rehabilitation, ensure medication adherence, educate caregivers, and act as the vital human link between stroke survivors and the health system.

With smartphones and telerehabilitation tools, these CHWs can even connect patients to specialists miles away.

Certification programs like those introduced by the World Stroke Organization (WSO) are also setting new global benchmarks for quality in stroke rehab centers—pushing hospitals to meet standards, improve clinician training, and ultimately serve patients better.

The reasons are complex. Non-communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol are widespread. Add to that sedentary lifestyles, smoking, and the lingering scars of war, and you have a region primed for a stroke epidemic.

While medical science has made tremendous advances—offering treatments that can reverse damage if given within the critical 4.5-hour window—the real challenge lies in access. Stroke care begins with a CT scan to determine whether it’s a bleed or a blockage, but in Jaffna, such imaging is available only at the Teaching Hospital or in the private sector. For many rural or low-income families, even reaching these facilities is a struggle.

The Mind Matters Too

But healing after stroke isn’t just physical—it’s deeply emotional. As Prof. L.L. Amila Isuru pointed out, post-stroke depression affects up to 40% of patients. Neuropsychiatric issues are still underdiagnosed, especially in countries where mental health remains stigmatized.

Yet these conditions dramatically affect recovery. Depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment not only reduce quality of life, but also impede adherence to therapies, increasing the risk of another stroke.

A comprehensive stroke response must therefore include psychological assessment, emotional counseling, and long-term follow-up—not just pills and procedures.

But amid these challenges, something extraordinary is happening in Kondavil. Led by the Family Medicine Unit and guided by Consultant Family Physician Dr. S. Kumaran, a team of health professionals has quietly redefined how stroke rehabilitation can be delivered in the most difficult circumstances. Their solution? Bring care home.

A Community-Led Solution

It started small, almost humbly. A handful of stroke survivors from the Nallur Medical Officer of Health (MOH) division—many unable to walk, speak, or even feed themselves—were enrolled in a novel program. The aim? To provide personalized, home-based care through a trained Community Health Worker (CHW) network.

These CHWs are not outsiders. They are members of the community, selected through a careful screening process, then trained in everything from medical first aid, nutrition, health education, and physiotherapy to emotional intelligence, gender-based violence prevention, and counselling. They are bridges between hospitals and homes, helping families navigate the complexity of stroke recovery.

Once trained, CHWs return to their communities, forming part of a multidisciplinary team: doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, pharmacists, nutritionists—and crucially, caregivers.

Healing Begins at Home

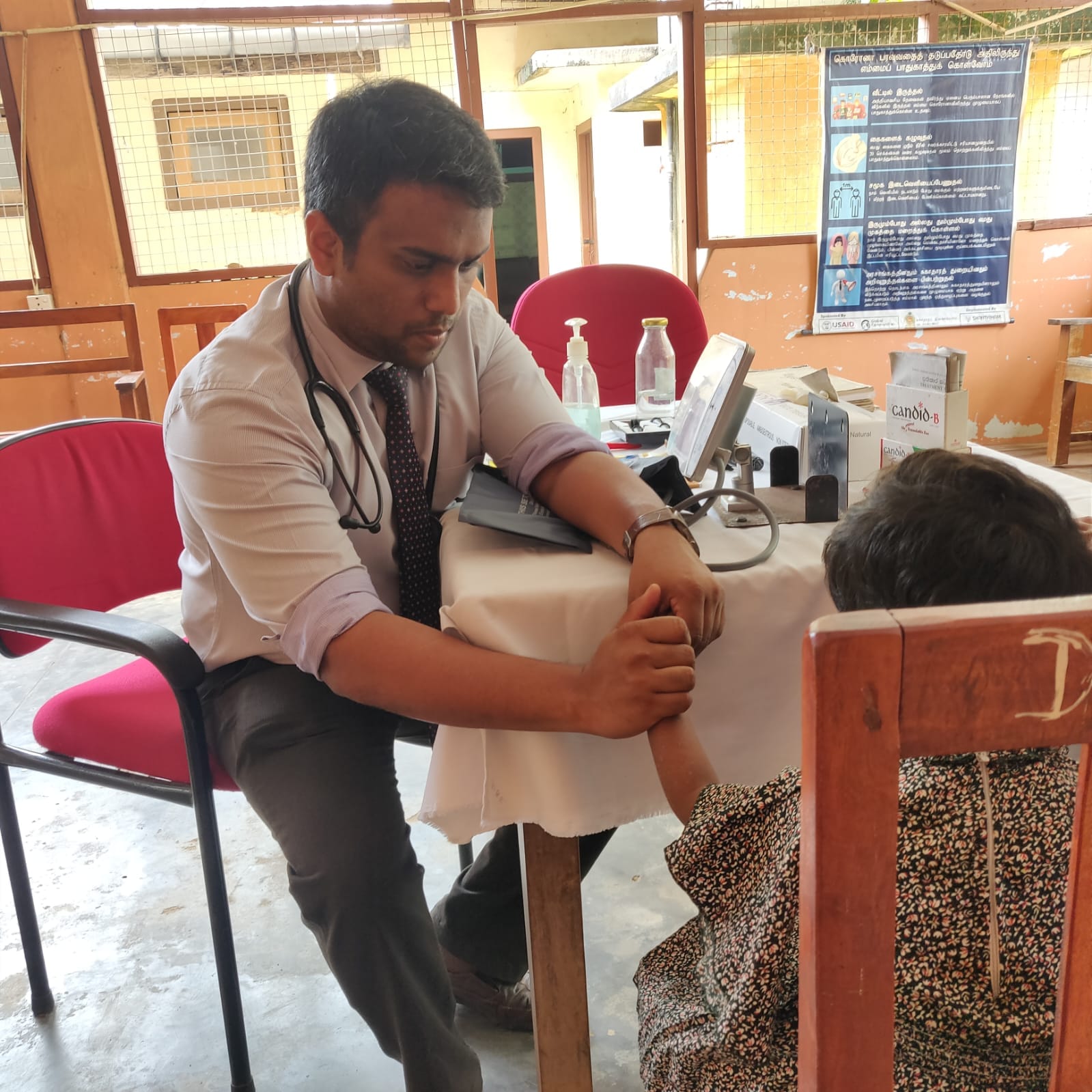

Patients are identified by the Family Health Center in Kondavil. The team then schedules home visits

- The doctor performs detailed assessments

- The nurse provides wound care and hygiene support

- The physiotherapist guides mobility exercises

- The nutritionist tailors meal plans based on affordability and need

- The pharmacist ensures medication adherence

- And the CHW, the everyday hero, returns week after week to monitor, encourage, and uplift.

One CHW shared, “Sometimes I feel like a daughter, a friend, a nurse, and a teacher all in one. But every time I see a patient smile or take a step they couldn’t before, it’s worth it.”

A Model to Follow

This initiative is more than a program—it’s a blueprint. In regions struggling with poverty, poor infrastructure, and fractured systems, community-based, people-centered stroke care isn’t just a stopgap—it’s the future.

Dr. Kumaran describes it best: “This is a complex adaptation for a complex problem. The CHW is the heart of our system—a human link between suffering and support.”

Kondavil’s quiet revolution offers a powerful reminder that stroke recovery doesn’t have to remain confined within hospital walls. With a people-centric approach from the medical fraternity, even life-saving care can be delivered—free of charge—right to your doorstep.