In Sri Lanka, landmines claimed countless lives and left many more—combatants and civilians alike—crippled, limbless, or permanently scarred. Yet their true infamy is often traced to one shattering moment: the first-ever landmine explosion in Jaffna on 23 July 1983, an event that many regard as the spark that ignited the civil war.

On that fateful day, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) buried a landmine on the Jaffna–Palaly main road, barely two kilometers from the heart of the city. When it detonated beneath an army truck and a jeep, 13 Sri Lankan soldiers—many of them young recruits—were killed instantly.

This was no ordinary ambush. It was the LTTE’s first successful use of a landmine against the armed forces, opening a deadly new chapter in asymmetric warfare. For many, it marked the ignition point of Eelam War I.

The repercussions were immediate and catastrophic. In Colombo and across the island, mobs unleashed fury on Tamil civilians. The violence of Black July 1983—murders, looting, arson, and mass displacement—remains etched as one of the darkest chapters in Sri Lanka’s history. Thousands of Tamil lives were destroyed in a matter of days, and the fragile social fabric of the nation was torn apart.

The war quickly spilled into the Eastern Province. At that time, I was stationed as the only surgeon in a civilian hospital on the edge of the front lines, in the adjoining district of Polonnaruwa—thrust without warning into the heart of a conflict that would rage for the next 26 years.

The Evolution and Horror of Landmines

The word “mine” derives from the Latin “mina,” meaning “vein of ore,” originally used to describe mineral excavation. Military engineers later applied the term to tunnels or buried charges used to topple fortifications during sieges. Over time, it evolved into a hidden explosive device, designed to disable vehicles or incapacitate people, and has become one of the most enduring weapons of modern warfare.

Landmines are typically buried in soil, concealed in vegetation, or fixed to stakes and trees, carefully camouflaged to avoid detection. They may be triggered by direct pressure, tripwires, tilt rods, magnetic influence, or remote detonation. Their invisibility makes them difficult to locate and devastating in effect.

Anti-vehicle (AV) mines were developed after World War I, primarily in response to the tank. The invention of trinitrotoluene (TNT) enabled reliable pressure-activated designs, and by World War II, steel-cased mines containing about 10 kg of TNT were widely deployed. AV mines are generally round or square, designed to detonate under the weight of heavy vehicles (120–150 kg). While intended for tanks, their impact on lighter vehicles is catastrophic, often causing total destruction and fatal injuries to occupants.

Anti-personnel (AP) mines, in contrast, are designed to incapacitate individuals. Requiring only the weight of a footstep or the disturbance of a tripwire, they cause blast injuries, traumatic amputations, or widespread shrapnel wounds. Their strategic purpose was often to wound rather than kill, thereby straining enemy medical resources. However, their indiscriminate nature has caused immense civilian suffering, especially in post-war regions where they remain active for decades.

The Claymore mine represents another class of AP weapon. Rectangular and usually command-detonated, it projects a fan-shaped spray of steel balls across a wide arc. Effective against troops in open areas or ambush situations, Claymores can kill or incapacitate dozens at once. Though often controlled by an operator, variants with tripwire detonation continue to endanger civilians long after conflicts end.

Together, AV mines, AP mines, and Claymores illustrate the evolution of the landmine from a defensive battlefield weapon into a global humanitarian crisis. Designed for war, they persist in peace, claiming lives and limbs long after the fighting has ceased.

My First Encounter with Landmine Injuries

My first encounter remains vivid: an army jeep carrying six soldiers struck a powerful mine. Three died instantly—mangled beyond recognition. The survivors were brought in with multiple life-threatening injuries. I had no prior training in war surgery, no reference books, no senior mentors, no smartphone, no internet. All I had was my basic surgical training and one guiding principle: save life first, then limb. That case became the turning point of my career. I realized I had to learn—fast.

The Early Learning Curve

In the absence of formal war surgery training, I travelled to Colombo to access the medical library, studied International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) war surgery manuals, World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, and journal articles, and learned on the job. I documented every case—through written notes, sketches, and photographs—not only for my own reference but also to train junior doctors, nurses, and paramedics. I delivered lectures on blast and landmine injuries and published my experiences in medical journals. Over time, our small hospital evolved into an informal teaching centre for war trauma care.

Patterns of Injury and Care of Victims of Mine Explosions

Managing these injuries in the field and in small hospitals was an immense challenge. Casualties often arrived without prior warning, having received little or no first aid at the site. Transport was slow and perilous. Field ambulances were rarely available; instead, the injured were brought in army jeeps or trucks navigating unsafe terrain. Helicopters were used only occasionally. Hospitals operated with limited surgical facilities and staff. At times, inadequate blood supplies and minimal anaesthetic support further complicated matters.

In response, teams developed improvised but effective strategies. Triage protocols prioritised life-saving interventions, ensuring that those most likely to survive received urgent care first. Damage-control surgery became essential, focusing on rapid haemorrhage control, prevention of contamination, and temporary wound closure to stabilise patients for later definitive surgery. All available staff, including non-medical helpers, were trained in basic haemorrhage control techniques to compensate for the shortage of trained medical personnel.

Definitive Care and the Multidisciplinary Approach

Patients requiring advanced reconstructive procedures were transferred to larger tertiary hospitals. There, multidisciplinary teams provided comprehensive care: orthopaedic surgeons managed fracture fixation, plastic surgeons performed complex soft tissue coverage, and physiotherapists promoted early mobilisation to prevent complications from immobility. Prosthetic technicians ensured the timely fitting of artificial limbs, while psychiatrists and counsellors addressed the profound psychological impact of these injuries.

Rehabilitation and Psychological Impact

Rehabilitation extended far beyond wound healing and limb fitting. Physical recovery included prosthetic training, gait rehabilitation, and strengthening exercises. Vocational training enabled many survivors to regain economic independence and re-enter the workforce.

Yet the psychological toll was often as severe as the physical injuries. Many survivors developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suffering from flashbacks, nightmares, anxiety, and depression. For women amputees in particular, social stigma compounded their suffering, leading to isolation and a diminished quality of life. True recovery demanded a holistic approach—combining physical rehabilitation, mental health support, family counselling, and community reintegration programmes.

Post-War Issues in Sri Lanka

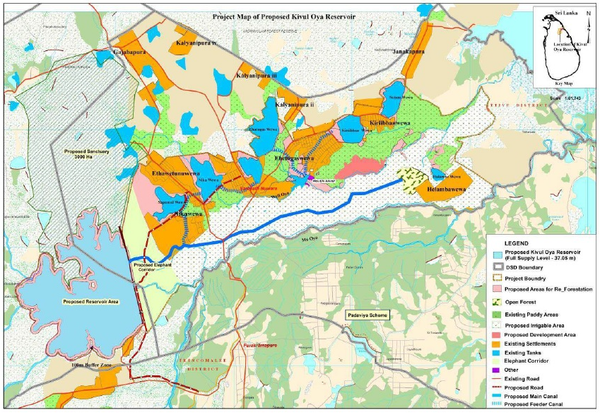

Long after the guns fell silent in 2009, the hidden threat of landmines—both anti-vehicle, anti-personnel, and other explosive remnants of war (ERW)—continued to haunt Sri Lanka’s Northern and Eastern Provinces. Cheap to produce, easy to deploy, and designed to maim, anti-personnel mines left vast stretches of land—fields, footpaths, and villages—contaminated and deadly. By the war’s end, more than a million unmarked and often undocumented mines were believed to be buried across several square kilometers in the North and East. These silent killers, capable of remaining lethal for decades, posed grave risks to farmers working the land, children at play, and displaced families returning home.

The danger crippled communities, stalled resettlement, and delayed development. The legacy of landmines extended far beyond human injury: contaminated soil, abandoned farmland, and shattered livelihoods scarred the landscape. Families remained uprooted, agricultural lands lay unused, and communities endured socio-economic stagnation—living each day under the shadow of hidden explosives. With over 800,000 displaced people awaiting return, urgent and sustained mine clearance became essential to prevent further casualties. Identifying and removing these deadly devices became a national imperative once the war had ended.

The Mine Ban Treaty and Sri Lanka’s path to a Mine–Free Nation

In response to decades of humanitarian crises caused by landmines, groups such as the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), founded in 1992, worked tirelessly to expose the suffering caused by mines in countries including Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Bosnia, and Angola. Their efforts were supported by organizations like the Red Cross and the United Nations, which consistently called for a global ban on landmines. These combined initiatives culminated in the Mine Ban Treaty of 1997, signed on December 3 that year and entering into force in 1999. The treaty prohibits the production, use, stockpiling, and transfer of anti-personnel landmines. Sri Lanka formally acceded to the treaty in December 2017, and it came into effect for the country on June 1, 2018. Under Article V of the treaty, Sri Lanka must declare itself mine-free by 2028.

Sri Lanka first initiated a mine action program in 2002, focusing particularly on the war-torn North and East and implementing the five universally recognized pillars of mine action under the coordination of the Sri Lanka Mine Action Program. However, with the escalation of the war, the program was forced to suspend operations.

Sri Lanka Mine Action Centre

The Sri Lanka Mine Action Program was initiated in 2002 with the assistance of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). In 2010, the Sri Lanka Mine Action Centre (SLMAC) was established under the Government of Sri Lanka to oversee all demining activities, ensuring both efficiency and safety. This organization has played a crucial role in coordinating national and international mine-clearance efforts, working in collaboration with the UNDP, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), the Geneva Centre for International Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), and various specialized demining groups.

Five Pillars of the Mine Ban Treaty

Sri Lanka’s engagement with the Five Pillars of the Mine Ban Treaty offers both a measure of hope and a framework for progress:

Demining in Sri Lanka

Mine clearance has been a vital part of the nation’s post-war recovery. Since 2010, the Sri Lanka Army Humanitarian Demining Unit (SLAHDU), together with international and local partners, has steadily reclaimed land metre by metre. More than 2.5 million explosive devices—including anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines—have been unearthed. Yet much work remains to be done.

The HALO Trust, the largest mine-clearance organisation in Sri Lanka, has been active since 2002. Concentrating mainly in Jaffna, Kilinochchi, and Mullaitivu, HALO has cleared over 114 square kilometres—roughly the size of 6,700 cricket fields—removing more than 270,000 landmines and one million items of ammunition. In Muhamalai, once one of the most heavily mined regions, HALO cleared an area three times the size of New York’s Central Park, lifting some 60,000 mines and enabling families displaced for more than 25 years to return. Today, HALO employs over 1,300 local staff, 40% of them women—many of them war widows who now earn livelihoods through this vital work.

The Mines Advisory Group (MAG) has also played a significant role, working in close partnership with the Sri Lankan government to restore land in the north and east.

Among national organisations, Delvon Assistance for Social Harmony (DASH), established in 2010 with Danish support, has grown into one of the most experienced local demining groups. Similarly, the Skavita Humanitarian Assistance and Relief Project (SHARP), founded in 2016, has cleared more than 17,000 explosive devices in the Northern Province, enabling over 3,000 people to resettle. Japan has been a key donor supporting SHARP’s work.

The SLAHDU itself, formed in 2002, has cleared several square kilometres of hazardous land using manual and mechanical methods, supported by specially trained dogs. Its efforts complement those of NGOs, reflecting a strong civil–military partnership within Sri Lanka’s mine action programme.

Together, these combined efforts have transformed once-lethal minefields into safe ground for farming, schools, and homes. While the journey toward a mine-free Sri Lanka is not yet complete, the steady progress demonstrates how determination, collaboration, and humanitarian commitment can restore both land and lives.

Mine Risk Education

Community-based awareness programmes in schools and villages have saved countless lives by teaching people how to recognise and avoid dangerous areas. According to the Sri Lanka Mine Action Report (SLMAC-2024), only 207 people have been injured by mines and ERWs since 2010, with no deaths reported to the SLMAC. This is a remarkable achievement when compared to other war-torn countries, where many civilians returning home have been injured or killed by explosive remnants of war.

Victim Assistance

For many long-term survivors, the war never truly ended. They continue to require revision surgeries for amputations, prosthetic replacements, and regular rehabilitation. From a psychological perspective, these individuals often face the invisible wounds of trauma: nightmares, flashbacks, anxiety, and the deep uncertainty of navigating a future forever altered by a moment’s misstep. Prosthetic centres, rehabilitation hospitals, and psychosocial counselling services provide vital support, though accessibility and resources remain uneven.

Jaffna’s Silent Pillar of Recovery: The Jaipur Centre for Disability Rehabilitation

The Jaffna Jaipur Centre for Disability Rehabilitation (JJCDR)—formerly known as the Jaipur Foot Programme—has been a cornerstone of victim assistance and humanitarian rehabilitation in Northern Sri Lanka. Established in 1987 as a direct response to the escalating civil war, the centre was created to serve individuals in urgent need of assistive devices, particularly those who had suffered war-related injuries. Initially supported by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), JJCDR has since grown into a dedicated, non-governmental social service organisation with a sustained commitment to both physical and psychosocial rehabilitation.

Throughout the civil conflict and in the years that followed, JJCDR played a pivotal role in restoring mobility, dignity, and hope to thousands of individuals, particularly amputees. The centre’s services have been critical in the Northern Province, especially in the Jaffna District, where the intensity of conflict, the demands of early resettlement, and the high population density produced a significant number of casualties and limb injuries.

I had the privilege of visiting this centre and meeting its staff, including those working in the workshop. What struck me most was that some of these staff members—disabled themselves through war-related amputations or other causes—had been rehabilitated at the very same centre. Their dedication and determination were unmistakable, driven by a clear mission to help others in need. The centre’s services extend beyond the fitting of prostheses for both upper and lower limbs, encompassing a wide range of orthotic devices and other appliances for the disabled. With support from the ICRC, the centre upgraded to world-class polypropylene prosthetic technology in the late 1990s, greatly enhancing the quality of care it provides.

According to available records, from 1986 to 2018, JJCDR registered 3,665 patients requiring prosthetic devices. Although the average number of new amputees registered annually during this period was 111, the post-war years saw a dramatic surge, peaking at 333 new registrations in 2010, just one year after the war ended. This reflected both the scale of unmet need during the conflict and the trust placed in JJCDR’s ability to deliver timely and effective rehabilitation.

The vast majority of those served were male, under the age of 35, and had sustained lower-limb injuries—93% of whom required prostheses for below-knee amputations. A significant 61.1% of amputations were directly related to the war, with landmines being the leading cause.

JJCDR’s approach has extended beyond physical rehabilitation to encompass comprehensive psychosocial support, enabling individuals not just to walk again, but to rebuild their lives, reintegrate into society, and regain economic independence. Its enduring presence and evolving capabilities have made JJCDR an essential institution in the region’s long journey from conflict to recovery.

Stockpile Destruction – The destruction of much of Sri Lanka’s anti-personnel mine stockpile reflects a firm commitment to treaty obligations.

Advocacy & International Cooperation – Continued collaboration with the UN Mine Action Service and the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) has ensured both technical expertise and funding support for sustained mine action. Sri Lanka cannot do this alone—international funding is a prerequisite. Countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, Australia, Norway, Switzerland, and Germany have contributed immensely to the post-war mine action programme, amounting to over 250 million US dollars. The continuation of this programme relies heavily on further overseas support.

Our journey alongside landmine victims has been shaped by necessity, resourcefulness, and a relentless commitment to healing and learning. As surgeons and caregivers, we have witnessed the resilience of the human body—how shattered limbs can be repaired, restored, and adapted through surgical skill and innovation. Equally, rehabilitation specialists and psychologists have reaffirmed the profound importance of healing the mind—helping survivors reclaim dignity, purpose, and hope.

Post-conflict mine action in Sri Lanka stands as a testament to national resilience and determination after decades of war. Beyond removing the deadly remnants of conflict, it has enabled resettlement, safer communities, and laid the foundations for lasting peace and development. The combined efforts of the Sri Lanka Mine Action Centre, UNDP, UNICEF, GICHD, international donors, and dedicated demining organisations have restored normalcy to once-devastated regions.

Yet challenges remain. Pockets of contamination persist in remote areas, demanding continued clearance, community education, and vigilance until the vision of a mine-free Sri Lanka—pledged under the Mine Ban Treaty—is realised by 2028. Sri Lanka’s mine action programme, transparent and collaborative, with minimal casualties, offers a model for other post-conflict nations striving for recovery.

The scars of landmines remind us that while wars may end, their weapons outlast the conflict, wounding both body and spirit for generations. The task before us is not merely to treat injuries but to restore lives and rebuild communities so they may thrive in peace. True victory will come when no child grows up fearing the ground beneath their feet, and when every step on Sri Lankan soil is taken in safety, dignity, and freedom.