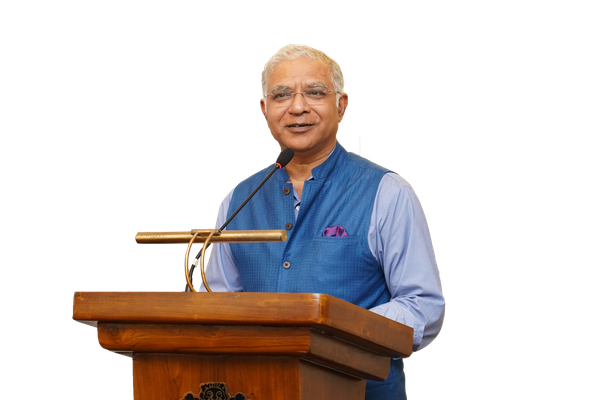

G. L. Peiris was at the epicentre of Sri Lanka’s peace negotiations with the LTTE and occupied senior office under three successive governments during one of the most consequential phases of the conflict. In his new book, The Sri Lanka Peace Process: An Inside View, he revisits that period with the benefit of temporal distance and retrospective clarity.

In this interview with Jaffna Monitor, Peiris confronts the charge that his narrative assumes the posture of a detached observer and explains why he opted for a consciously analytical mode of inquiry. He re-examines the role of foreign facilitation, the strategic miscalculations of both the LTTE and the State, and what Sri Lanka’s experience discloses about the constraints—and contingencies—of negotiated peace.

I will start with the question that writer M. R. Narayan Swamy wrote in Jaffna Monitor: “Reading this otherwise invaluable book will give the impression that academic-turned-politician G. L. Peiris was a distant observer of Sri Lanka’s peace process and not the government’s chief negotiator.” How would you like to respond to it?

The entire purpose of writing this book was to present a dispassionate assessment—to step back and look at the peace process objectively. It is true that I played a central role in Sri Lanka’s peace efforts under three different governments. The process began under President Chandrika Kumaratunga, was taken to the international level under Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, and reached its final phase under President Mahinda Rajapaksa. In that sense, I was involved throughout, and there was a clear thread of continuity.

Over the years, many people—both in Sri Lanka and in the United Kingdom—pointed out to me that there was a serious gap in institutional memory regarding the peace process. This was something I encountered frequently during my time at the University of Oxford and at Christ’s College, University of Cambridge. That gap, I felt, needed to be filled.

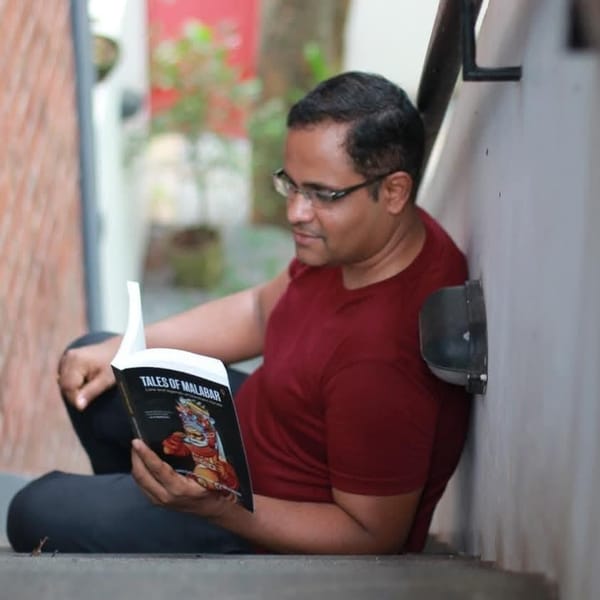

There are, of course, existing accounts. On the LTTE side, Anton Balasingham wrote War and Peace. Austin Fernando, who served as Secretary to the Ministry of Defence, authored My Belly Is White, which naturally focuses on defence-related aspects. John Gooneratne wrote The Peace Process from the Second Row, offering the perspective of an official. There is also To End a Civil War: Norway’s Peace Engagement in Sri Lanka (2015) by Mark Salter.

However, what was missing was an inside account by someone who was centrally involved in the process from beginning to end.

In writing this book, I was very conscious of the need to remain as objective as possible. I did not want to defend decisions or events simply because I had been personally involved in them—that would have resulted in a biased and coloured narrative. The deliberate intention was to detach myself, to stand back, and to assess the process critically.

The war ended in 2009. Writing fifteen years after the event, once the dust had settled, made it easier to take a dispassionate view. I was not writing as an apologist, nor was I attempting to justify or defend what was done. On the contrary, the purpose was precisely the opposite: to offer an analytical, systematic evaluation of the peace process—its strengths, its failures, and its structural deficiencies. That, fundamentally, was the reason for writing this book.

So the distant observer position you take in your book was a deliberate choice?

Yes, it was very much a deliberate choice. I consciously maintained that distance in order to gain an overall view—to examine the peace process as an outsider might. At the same time, I did draw upon my own personal experience, but not with the intention of justifying every decision or outcome.

Doing so would have diminished the value of the book, particularly because it is being read a decade and a half after the events it examines.

So, if someone argues that writing in hindsight is far easier than being in the role of the chief negotiator at the time, how would you respond?

That is correct, and I think it is a fair comment. When you are in the midst of a negotiation, you are compelled to make decisions on the spur of the moment. The outcomes are uncertain because the trajectory is unclear—you do not know how events will unfold or where they will ultimately lead. At that point, everything is fluid and indeterminate.

More than a decade after the events, however, there is a far greater measure of clarity. Looking back, the purpose of this study was to undertake a detailed examination of the different dimensions of the Sri Lankan peace process. At the same time, I was conscious of the fact that peace processes are currently unfolding in very different parts of the world—whether between Thailand and Cambodia, in Gaza, or in Ukraine.

I do not believe that the experience of one country can simply be transplanted onto another. That is neither possible nor desirable, because circumstances, nuances, and priorities inevitably differ. Nevertheless, there are valuable lessons that can be drawn from the Sri Lankan experience.

One such question concerns foreign facilitation. In our case, Norway played that role. When President Chandrika Kumaratunga initiated the peace process, she began with what came to be known as the Jaffna Talks soon after her election. These involved direct engagement with the LTTE. A team led by her Secretary, Mr. Balapatabendi, was sent to Jaffna, and while there were face-to-face meetings, much of the engagement took place through correspondence. This phase—often described as the epistolary phase—had neither a mediator nor a facilitator; it was conducted directly between the President and the LTTE.

That process eventually broke down, and it was then felt that some form of foreign assistance was not merely useful, but probably necessary. In many peace processes, facilitation of some kind is involved. The crucial question, however, is how that facilitation should be structured. Should the parties retain complete ownership of the process, or should the facilitator be given a more active role? On questions such as these, the Sri Lankan experience has comparative value.

There is also the economic dimension. At the time, there was a belief that a large infusion of foreign resources would help resolve substantive political issues—the so-called economic dividend. That expectation did not materialise. Why did it fail, and what lessons can be drawn from that negative experience?

Another issue relates to sequencing. A conscious decision was taken to prioritise rehabilitation, livelihoods, and resettlement in the North and East—what are often described as “existential” concerns. The assumption was that these should be addressed first, and that political issues such as power-sharing, devolution, federalism, or self-determination could be dealt with later.

In practice, however, this clear-cut separation did not work. Certain “existentia”l issues could not be resolved without making significant political changes. The two strands were deeply interlinked.

These are among the central issues that emerge from the Sri Lankan peace process, and they remain relevant when considering peace efforts elsewhere. Reflecting on them in retrospect allows us to assess how such experiences might contribute—constructively and cautiously—to the design and management of peace processes currently underway in other parts of the world.

So, would you recommend a foreign facilitator in peace processes in other countries? Or would you rather recommend that parties reach an understanding among themselves to resolve the problem?

No, I would not make a general recommendation. In Sri Lanka’s case, some form of assistance became necessary, particularly after the failure of the Jaffna Talks. But facilitation does not necessarily have to be foreign.

Take South Africa as an example. They consistently refused foreign mediation or facilitation. Their position was clear: this was their problem; they understood it best; and they had the strongest stake in resolving it themselves. Accordingly, they chose to manage the process internally.

Crucially, South Africa also had individuals within the country who possessed immense moral stature and were acceptable to all sides—figures such as Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu. They commanded extraordinary moral authority and played a decisive role, particularly through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

At its core, mediation simply means bringing two sides together through an independent party. That independent party need not be foreign; it can just as well be domestic. However, in Sri Lanka, we did not have individuals of comparable stature whose moral authority could command universal acceptance. In that context, the facilitator had to come from outside.

When selecting a foreign facilitator, careful consideration was given. Norway was chosen for several reasons. First, there was a deliberate decision to avoid a country with overwhelming military, political, or strategic clout. In particular, India was uncomfortable with a major power assuming such a role. We felt that a dominant state could intimidate the parties and inhibit frank and open engagement. What was preferred was a small country, without hegemonic ambitions in South Asia.

Norway also had prior familiarity with Sri Lanka. It had been involved in development work in the southern part of the country, especially in the Hambantota District, including in projects related to minor roads, irrigation, and rural development. In addition, Norway possessed well-recognised expertise in peace facilitation.

For these reasons, Norway was selected. That said, I would hesitate to offer prescriptive advice to others. Local circumstances are decisive. You cannot take one peace process and transplant it wholesale into another context. What you can do is study other experiences carefully, draw lessons from them, and then adapt and modify those lessons to suit the specific realities of your own situation.

It seems like you are not happy with Norway—either with the way they negotiated or how they functioned. Would you say that assessment is correct?

No, that would be an oversimplification. As I state in the book, Norway did its best in an extremely difficult situation.

Norway’s task became far more challenging after 9/11. The global environment changed dramatically. The United States had already banned the LTTE in 1997, and after 9/11 there was a much more robust international hostility towards movements regarded as terrorist organisations. This altered the context within which the Norwegian facilitators had to operate.

As a result, Norway found itself increasingly isolated. Following the assassination of Lakshman Kadirgamar, the European Union banned the LTTE in 2006. After that, no European country was willing to host the LTTE on its soil. With the exception of Geneva, there were virtually no European venues available for meetings between the Sri Lankan Government and the LTTE.

This development had serious consequences for the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM), which comprised personnel from Nordic countries such as Finland, Denmark, and Sweden. Once the EU ban came into effect, these countries withdrew from the SLMM because their governments had formally proscribed the LTTE. As a result, the Monitoring Mission could no longer function effectively.

These were formidable constraints under which the Norwegians had to operate. It would therefore be unfair to judge them harshly, given the extremely hostile international environment they faced. That said, there may have been errors of judgment in certain areas.

One example relates to the preparations for the Tokyo Donor Conference in June 2003. There were two preparatory conferences: one held in Oslo in November 2002, and another in Washington, D.C. in April 2003, roughly two months before Tokyo.

The LTTE, however, could not attend the Washington conference because they had been banned by the United States. They were deeply resentful of the fact that a preparatory meeting for Tokyo was being held in a country from which they were excluded. They regarded this as a deliberate humiliation and a breach of faith.

Their argument was that they needed to present their case directly to the international community. They pointed out that large numbers of people under their control were living in camps, unable to return to their homes, and suffering severe economic deprivation. To articulate this effectively, they believed physical presence was essential.

Because they were excluded from Washington, they felt marginalised. In that context, it may have been preferable for the Norwegians to suggest that the preparatory conference be held in a country where both the Government and the LTTE could participate.

The Norwegians, however, often took the view that ownership of the process lay entirely with the parties. In other peace processes—such as Nepal, Israel–Palestine, or Aceh—facilitators operated under UN mandates or within stronger international frameworks. In Aceh, for instance, Martti Ahtisaari and the European Union played a far more directive role.

In Sri Lanka, there was no such mandate. Norway was invited solely by the two parties—the Government and the LTTE—and its authority flowed entirely from their consent. Consequently, the facilitators believed they had to operate strictly within the parameters set by the protagonists.

That said, facilitation is not a purely mechanical exercise; it requires imagination and initiative. The Norwegians did show leadership in many areas. They played a key role in drafting the Ceasefire Agreement, were deeply involved in negotiations surrounding the proposed Interim Self-Governing Authority, and were active in efforts to establish a joint mechanism following the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami.

So they did not merely confine themselves to narrow instructions from the parties; in many respects, they went beyond that. Unfortunately, when it came to the preparatory donor conference before Tokyo, the LTTE withdrew from the peace process and never fully returned. They boycotted the Tokyo Conference altogether.

The central significance of the Tokyo Conference lay in the fact that, after nearly thirty-five years of brutal conflict, the Government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE were expected to appear together before the international community to seek support. Once the LTTE chose not to attend, that core objective was largely lost.

These are areas where the Norwegian facilitators might have acted more proactively. In the book, I have criticised them where criticism is warranted, acknowledged their contributions where credit is due, and recognised the inherent difficulty of the task they undertook. It was, by no means, an easy assignment.

How would you describe the LTTE’s intention during the peace process? Were they genuinely committed to peace, or were they merely buying time—perhaps to rearm—given that you were dealing with one of the most hard-line and intransigent movements? Were they really serious about the peace process?

The first thing to note is that Prabhakaran was convinced that he was militarily invincible. That belief was deeply embedded in his psyche.

He believed that the Sri Lankan military might win one or two battles here and there, but that they could never defeat the LTTE decisively. In his view, a military solution was simply not possible. He was absolutely convinced that the Sri Lankan Government could not defeat him.

Once you start from that assumption, there is a clear limit to the concessions he was prepared to make. Why should he make concessions, if he believed he could not be defeated by the Sri Lankan Armed Forces? That is the first reality.

What the LTTE were really aiming at was to consolidate the authority they had already acquired. They were effectively running that part of the country. The Ceasefire Agreement, along with the demarcation of forward defence lines, reinforced the recognition that they exercised effective control over those areas. In other words, they were ruling that part of the country de facto.

They were therefore very keen on an interim arrangement—specifically the Interim Self-Governing Authority (ISGA)—which would convert their de facto authority into de jure authority. They already had their own police force, their own courts, their own revenue and customs systems, and administrative structures. All of this power was already being exercised in practice.

The ISGA was attractive to them because it would bring formal recognition—recognition by the Government of Sri Lanka and, crucially, by the international community. That was of immense value to the LTTE. This is why they were so focused on the interim self-governing authority.

The Government’s response was that an interim arrangement might indeed be useful, and perhaps even necessary, in such a complex situation. But that interim arrangement had to be linked to a final political settlement. There had to be a clear nexus.

The difficulty was that the LTTE were not interested in anything beyond the interim arrangement. Once they obtained the interim structure, they would have achieved everything they wanted, and they had little interest in proceeding further with the peace process.

So, in answer to your question, I would say that a final political settlement was not of real interest to them. What they were keen on was the interim structure.

I had come to know Anton Balasingham quite well, both formally and informally. On one occasion, I said to him that this seemed to be going nowhere—almost like a Greek tragedy—and asked him where he thought all of this was heading. I pointed out that there still appeared to be a small window of opportunity, and asked why it could not be used while it existed.

His answer was interesting. He said, “I have done everything I possibly can, more than I should. But Prabhakaran is surrounded by people who cut him off from the world of reality.”

He also told me that his visits to the Vanni had become infrequent, and that when he did go, it was only for short periods. This was because his wife, Adele, who was a hospital nurse, was very concerned about Balasingham contracting mosquito-borne diseases, as his resistance level was very low. As a result, his access to Prabhakaran was limited.

As is usual in many power structures, his absence was exploited by others who were jealous of his special relationship with the Supremo, Prabhakaran. They planted various seeds of suspicion in Prabhakaran’s mind.

Balasingham was the only person who truly understood the reality of the situation. He was a political scientist and a well-read man, and he knew where all of this was likely to end. But he told me that he had exhausted all avenues—he had tried to persuade Prabhakaran, but it was an impenetrable wall. You could not break through it. Prabhakaran had a very fixed mindset.

That, in essence, was the reality of the situation.

You said Balasingham understood the end. What do you mean by the end—the end of the LTTE, or the end of the peace process?

I think Anton Balasingham understood that the LTTE would be defeated militarily and destroyed. He knew that it would ultimately end in the destruction of the LTTE.

Because of that understanding, he did everything he could to promote and negotiate a settlement.

The other members of the LTTE delegation—S. P. Thamilselvan, Karuna Amman, and others—were essentially military people. They were fighters. They were not thinkers.

Balasingham was a thinker. He had a grasp of the issues that nobody else on that side had. He also lived in London, which gave him a broader international perspective.

How serious was the Government about the peace process? If someone argues that the Government was also buying time through the peace process, not genuinely serious about devolution or a peace agreement, and was waiting for the moment when it could say, “Now we can defeat the LTTE”, how would you respond?

No, that is not true.

You see, there were different approaches taken by different actors. Take Chandrika Kumaratunga, for instance. She had a particular policy, which she described as “war for peace.”

In her thinking, war was necessary against a recalcitrant rump within the LTTE—a hard core that could not be satisfied in any other way. They would not compromise; they would not accept a political settlement, however reasonable. Chandrika believed that such elements had to be militarily defeated.

But this was not her view of the Tamil people. She always made a clear distinction between the Tamil people and the LTTE. Even within the LTTE, she believed there were more moderate sections—people who were open to reason—alongside a hard core. So, in her view, war was necessary only against that hard core.

For the Tamil people, her approach was completely different. That is where initiatives like the Sudu Nelum movement came in—an effort to promote amity and goodwill between Sinhala and Tamil communities. While I was in charge of constitutional arrangements, the Sudu Nelum movement was led by Mangala Samaraweera, who had a genuine passion for harmony between the two communities.

For Chandrika Kumaratunga, war was necessary, but it was not the main objective. The main objective was bringing people together—encouraging greater interaction between Tamil and Sinhala children in schools, promoting contacts of various kinds, not only political but also through sports, education, and literary activities. That was very much her thinking: war for a limited purpose, alongside broader initiatives aimed at reconciliation.

That said, Chandrika always regarded the LTTE as an adversary—someone you had to talk to, but always bearing in mind that their aspirations and political culture were very different.

Ranil Wickremesinghe, on the other hand, had a different approach. For him, the peace process was closely linked to his broader economic policy. He followed a neoliberal approach and wanted massive investment flowing into the country. Central Bank reports at the time showed clearly that Sri Lanka’s economy was suffering because of the war.

In my view, Sri Lanka’s most successful Finance Minister was Ronnie de Mel, and he stated publicly on many occasions that there was no future for Sri Lanka’s economy if the country continued to spend enormous sums on war. So the war had to stop if Sri Lanka was to develop.

Ranil wanted to connect Sri Lanka with the world—through investment, trade, and economic openness. To do that, the war had to end. He therefore negotiated with the LTTE in good faith. He also believed in the idea of an international safety net—the international community acting as guarantors, encouraging and supporting the process, and providing substantial financial assistance.

So the international community was not a passive observer; it actively supported the peace process and contributed significant material resources.

Therefore, the cynical view that the Government was merely buying time through the peace process until a military victory became possible, is not correct.

Then what was in the mind of Mahinda Rajapaksa?

Mahinda Rajapaksa was elected in 2005. He believed that, in the end, military action might be necessary.

The decisive moment came when the LTTE cut off the water supply at Mavil Aru, which directly affected farmers. He felt that military action had become absolutely necessary, because otherwise the farmers would starve, and their livelihoods would be destroyed.

Even then, he did not stop negotiations. He sent delegations first to Oslo, and then to Geneva. But by that time, he had become convinced that the LTTE was not sincere and would not agree to any political settlement. In his own mind, he was convinced of that.

After Mavil Aru, he felt that there was no alternative.

He then reoriented the idea of the international safety net. Instead of relying on Western countries—which were challenging Sri Lanka in the Human Rights Council in Geneva—he developed strong relationships with China, Russia, Czech Republic, Iran, and Libya, to secure military equipment, financial resources, and other forms of support.

He then prepared for a full-scale war.

You said that the Government was serious about the peace process. But the same Government facilitated the defection of Karuna Amman, which proved costly to the LTTE. How do you explain that?

No, Karuna’s defection was a reality that the LTTE itself had to face.

Karuna Amman was the most effective military commander of the LTTE, and he dominated the Eastern region. So the loss of Karuna meant that the entire Eastern flank was lost to the LTTE. But you cannot say that the Government was entirely responsible for that.

Karuna himself explained that his thinking began to change because of his extensive travels. Norway facilitated these travels for LTTE representatives across Europe to study federal systems of government. The Norwegians felt that the LTTE had very little exposure to the outside world and lacked even a basic understanding of how such systems functioned. So they believed it was important to give the LTTE an opportunity to observe them directly.

Norway also negotiated with the University of Bradford in England to provide a short course for LTTE representatives. As a result, there was considerable travel. Karuna later said that this exposure opened his eyes to the world beyond the Vanni, and that he began to rethink his views after seeing these systems firsthand.

He also became increasingly aware that LTTE cadres in the Eastern Province were being badly treated. He felt there was clear discrimination between the North and the East. Opportunities were largely given to LTTE cadres from the North, while those from the East were treated merely as cannon fodder.

As a result, Karuna began to take a more independent line.

When this became evident, Prabhakaran summoned him to the Vanni. Karuna refused, because he believed that if he went, he would be killed. That sense of grievance grew stronger and eventually culminated in his defection from the LTTE.

The Government was not an active party in the initial stages of this development. There were internal reasons that pushed Karuna in that direction. However, once the defection occurred, there was some degree of collusion between Karuna and the Sri Lankan Armed Forces. They did work together after he broke away.

So you mean to say that the Government at the time played no role in dividing Karuna Amman and the LTTE?

I do not think the Government at that time played a very active role. The Government was observing what was going on, and when Karuna Amman defected, then of course, naturally, the Government took advantage of the situation.

That was a major factor in the military defeat of the LTTE.

Then how do you say that the Government was serious about the peace process?

You see, by that time, the bona fides of the LTTE were being seriously questioned.

Take several factors. One was the continued recruitment of child soldiers. In a war of attrition, this was a way of replenishing depleted ranks. There was tremendous resentment about this in the South of the country.

As a result, a perception began to take hold in southern Sri Lanka that the Government was being taken for a ride—that the LTTE was deceiving the Government.

Then there was the issue of so-called “political work” under the Ceasefire Agreement. This was a very awkward provision. The CFA stipulated that, once the truce was signed, after 30 days, 50 LTTE cadres would be allowed to enter Government-controlled areas for political work. After 60 days, another 100 cadres could enter. After 90 days, all unarmed LTTE cadres could enter Government-controlled areas for political work.

But there was no genuine political work. Instead, these cadres entered Government-controlled areas and intimidated and terrorised people, particularly in areas under the influence of Douglas Devananda. So this so-called political work became a sham.

At the same time, the conscription of child soldiers continued, and the Sea Tigers were being used to bring large quantities of arms and ammunition into Sri Lanka. On all these fronts, it appeared that the Government was being deceived.

Then there was the role of the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM). Under Article III of the Ceasefire Agreement, the SLMM had wide authority. But in practice, it became almost totally ineffective.

There were instances where SLMM personnel themselves had to flee for their lives. On one occasion, after intercepting an LTTE vessel, an explosion occurred and Norwegian monitors had to jump into the sea, remaining in deep waters for about fifteen minutes until they were rescued by the Sri Lanka Navy. So instead of monitoring others, they were struggling to save their own lives.

All of this created a very negative impression. The LTTE appeared to be acting with impunity, while the Monitoring Mission seemed unable to enforce compliance. As a result, public opinion shifted dramatically.

When the peace process began, it enjoyed nearly 90 percent approval in the South, including among Sinhala voters. But as these developments unfolded—child recruitment, abuse of the political work provision, arms smuggling by the Sea Tigers—the approval rating steadily declined. By the end, support in the South had fallen to below 15 percent.

This decline was driven largely by the LTTE’s behaviour, which became increasingly unacceptable. Sinhala public opinion came to view the process as a journey to nowhere—a process through which the LTTE sought to obtain what it wanted by flagrantly misusing the peace process.

As a result, the credibility of the peace process itself collapsed. Credibility was the central issue.

As the chief negotiator and also as an educationist, you must have studied in great detail the psyche and personality of the LTTE supremo, Velupillai Prabhakaran. What is your assessment of him? He is the man who started a movement with a single pistol and went on to build a tri-forces structure. How do you see him?

I never met him. I never had a face-to-face meeting with him throughout the peace process. He was represented by Anton Balasingham, who was my counterpart.

So I cannot speak from direct personal interaction. I did not speak to him, and I have no direct knowledge of his personality, except what I gathered in the course of the peace process.

What I did gather was that he had a one-track mind—that militarily, he believed he would not be defeated. He was also unwilling to commit himself to any definite political position.

On devolution, for instance, there was never a serious discussion about federalism, because Prabhakaran did not want it. When Anton Balasingham agreed to pursue devolution within a federal framework—what came to be known as the Oslo Declaration—he incurred Prabhakaran’s displeasure.

Balasingham did not have Prabhakaran’s explicit approval at that stage, but given the relationship between the two, he felt he would be able to obtain it later. That did not happen.

The diaspora strongly opposed the Oslo formula, and Prabhakaran then found fault with Balasingham, asking why he had taken that position. After that, Balasingham withdrew and lived in relative isolation in London.

Prabhakaran was not prepared to take any definite stand on political issues. He was unwilling to do so largely because he believed that, ultimately, he did not need to make concessions—because he thought he could win the war.

To that extent, he had a very fixed mindset, with no flexibility and, indeed, no fragmentation in his thinking.

You spoke highly of Anton Balasingham. What is your assessment of him?

He was an astute politician. He had a strong knowledge of the subjects he was dealing with, and he had read widely. His book is very interesting from many points of view—it is closely reasoned and well argued.

However, he had very limited control, because as the peace process progressed, he was given less and less leeway by Velupillai Prabhakaran. As a result, his room for manoeuvre steadily diminished.

You noted in your book that President Chandrika Kumaratunga should not have been kept out of the peace process. Why was she kept out?

She was kept out because there was no trust or confidence between Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and President Chandrika Kumaratunga. They belonged to two different political parties and were political rivals, both preparing for a presidential election in which they would be opposing candidates. As a result, the level of mutual confidence between them was extremely low.

However, excluding Kumaratunga necessarily meant that the peace process was greatly weakened. As President, she commanded the armed forces. If she was completely sidelined and left out of the process, the military could not be fully brought into it. The President and the armed forces were closely aligned, and as the process moved forward, they became increasingly hostile to it.

She also exercised ultimate control over the constitutional system, which meant that she necessarily had a role to play. At a critical point in the process, she dismissed three ministers from Ranil Wickremesinghe’s Cabinet and took over those portfolios herself—something she was fully empowered to do under the Constitution. She was an all-powerful Executive President.

She later exercised those presidential powers to dissolve Parliament and ultimately succeeded in getting her own party elected. It was therefore an unequal contest, because the Constitution placed her at a tremendous advantage. Keeping her out of the peace process meant that the process could not progress beyond a certain point.

You were one of the powerful ministers under Mahinda Rajapaksa when he launched the war. In your view, what made him believe that Prabhakaran could be defeated?

At one point, he said, “Look, Prabhakaran is a product of the jungles of the North, and I am a product of the jungles of Ruhuna. So let us pit ourselves against each other and see who will win.”

Mahinda Rajapaksa was convinced that, if there was a clear war strategy and, above all, firm political will, victory was possible. Secondly, he believed that the necessary resources and funding had to be made available.

He also had complete faith in his brother, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who was the Secretary of the Ministry of Defence. There was a symbiotic relationship between the President and the Defence Secretary.

So it was a combination of these factors. He felt that if there was a definite commitment, if the required resources were provided, and if there was close coordination with the military, then victory was possible. In his own mind, he was fully convinced of that.

So if I say Velupillai Prabhakaran and Mahinda Rajapaksa were two sides of the same coin, would you agree?

No, that is not correct. Rajapaksa was also a very successful politician. He did many things for the country—infrastructure development, highways, ports, and so on.

He spearheaded economic development that would not have been possible while the war was ongoing. So you cannot compare the two in that sense.

However, his attitude was this: if Prabhakaran challenged him, he was prepared to accept that challenge.

With the benefit of hindsight, do you think the killings of innocent Tamils in the final phase of the war could have been avoided had the peace process succeeded?

That is precisely why I have said that the peace process should not have failed. There were plenty of chances—plenty of opportunities—but they were all spurned because of the conviction that, in the end, the LTTE could win militarily.

Had that not been the case, none of those tragedies would have occurred.

Even now, there are residual problems. There is a Geneva process, and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has established special mechanisms to gather evidence and examine allegations.

All of this has come about because every opportunity that existed for a reasonable solution to be worked out was missed.

You were a central figure in the 2000 Constitution Draft, which was never implemented. Do you believe that framework could have prevented some of the constitutional and political crises Sri Lanka has faced since? And is it still relevant?

That was the most comprehensive constitutional proposal ever worked out in Sri Lanka. It was presented to Parliament in August 2000. The President—Chandrika Kumaratunga—came to Parliament herself to address the House and to support it. I presented it as Minister of Constitutional Affairs.

We had worked on it for more than a year. At that time, the Attorney General was Sarath Silva, who later became Chief Justice. He was closely involved in the process. Jayampathy Wickramaratne and I worked very closely together. Asanga Welikala, who is now a Senior Lecturer in Public Law at the University of Edinburgh, was also part of the team.

We worked very hard on it. It was a complete constitution.

It failed not because of its content, but because of intense political rivalry, which is part of Sri Lanka’s political culture. The same adversarial attitudes came into play, and unfortunately, that is why this serious attempt at constitutional reform did not succeed.

So do you think that the constitutional draft is still relevant?

A lot of water has flowed under the bridge over the last quarter of a century.

But there are still elements of it which, if suitably adapted, modified, and refined, can be drawn upon.

You cannot simply copy it or apply it mechanically twenty-five years later. But there are aspects of it that can still be used in a modified form.

You worked closely with Neelan Tiruchelvam on the constitutional draft, and you spoke passionately about him in the documentary Neelan: Unsilenced. How do you remember him?

Neelan and I were together at the University of Peradeniya as undergraduate students. He was one year senior to me. I went to the University of Oxford on a scholarship, and he went to Harvard University on a scholarship.

We entered Parliament together in 1994. We worked very closely in 1995 and 1996 on the constitutional draft. Those drafts were prepared jointly by Neelan and me.

Neelan was killed by the LTTE because the LTTE did not tolerate moderate Tamil politicians. That is why he was assassinated on the eve of his departure to Harvard University, where he was to take up a senior fellowship. The LTTE feared that he would influence thinking internationally.

In fact, any Tamil who adopted a view different from Prabhakaran’s had to be eliminated—that was the LTTE’s ideology.

Had Neelan lived, he would have continued to make meaningful contributions to this country.

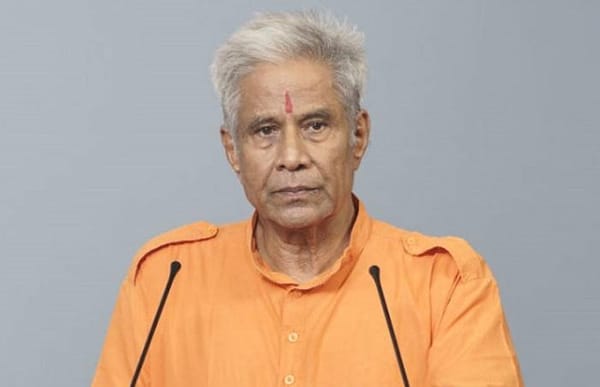

What do you think about the arrest of Douglas Devananda?

There is no doubt that Douglas Devananda contributed to the defeat of the LTTE and, in that sense, to the peace that Sri Lankans enjoy today. Both we and the government must bear that in mind. He was a major force in the Jaffna islands.

Of course, this does not grant anyone immunity from accountability in all matters. But his role is a significant factor that cannot be ignored; it is a very relevant consideration.

Taken together, these individuals and developments made it possible to bring the war to an end. Otherwise, the conflict would have continued for much longer, with the loss of many more lives.

I am asking this question not in your capacity as a politician, but as a former Vice-Chancellor and an educationist. How do you view the proposed educational reforms?

It is now clear that the reform has not been thought through carefully. The most serious problem, in my view, is that implementation is not possible under present circumstances.

There are some good aspects to the reform, no doubt. But to implement it properly, you need infrastructure—smartphones, computers, reliable internet access, and supporting facilities. How are you going to ensure that all schools have these facilities?

Children from affluent families and children from poor families are ultimately expected to sit for the same examinations. Therefore, they must have equal access to resources. Unfortunately, instead of narrowing this disparity, the new educational reform is actually widening it.

Not all students start from the same position. For such a reform to work, teachers themselves must be properly equipped—with training, technology, and institutional support. In many rural settings, this is simply not possible at present.

So the problem is not the idea alone, but the gap between policy and ground reality. Without addressing infrastructure, inequality, and teacher preparedness, the reform risks deepening existing educational inequalities rather than correcting them.

What is your assessment of the current National People's Power (NPP) Government?

A lack of competence is being clearly demonstrated in many situations—simply because they have no experience of governance. They have never had exposure to running a government, and as a result, they are making a series of mistakes.

There is also a clear reluctance to consult. How can you carry out a comprehensive education reform without close consultation with principals, teachers, and others who are directly involved? That consultation has not happened.

As a result, there is a serious disconnect. Policies appear to have been worked out by party cadres and advisers around the Government, with grossly inadequate consultation. One of the main problems is that they do not trust anyone outside their closed circle.

It is very difficult to run a government in that way. The quality of human resources in the country is actually very high, but you have to draw on that collective expertise. You need to seek advice, issue discussion papers and white papers, and allow proposals to evolve over time.

That has not happened. Teachers were not involved. Even members of the Government themselves often do not have a clear conception of what is being proposed. There is also a serious problem in the relationship between political authority and the senior bureaucracy—the public service is simply not clicking with the political leadership.

We see this in practice. Grama Niladhari officers, for example, have said that they are opting out of responsibilities related to disaster-relief delivery. They have stated publicly that they were not consulted, were not given clear guidelines, and received no proper instructions. Some have even withdrawn from these duties. This shows a deeper problem: the chemistry of working with officials and stakeholders is missing. That is one of the major deficiencies I observe in the way this Government is functioning.