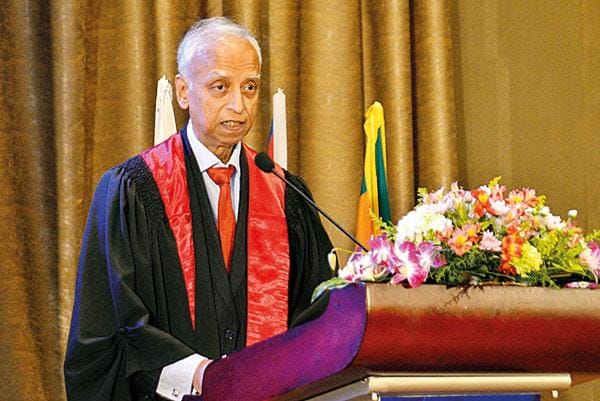

There is a photograph somewhere in the archives of British medical history: a Tamil man from war-torn Sri Lanka, standing in the wood-panelled chambers of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, holding a gavel once wielded by some of the most powerful physicians in the Western world.

It shouldn't have happened.

Not to a boy from Jaffna. Not to someone who began his career in a country that would soon tear itself apart. Not to a Tamil doctor in an era when the world chose to see his people only through the prism of conflict rather than contribution.

But Professor Sir Sabaratnam Arulkumaran never waited for permission to be extraordinary.

Over 45 years, he has pioneered techniques that slashed maternal and newborn mortality across continents—reshaping the seconds between life and death in delivery rooms. He ascended to the presidency of three of the world's most prestigious medical institutions: the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), and even the British Medical Association itself.

By 2009, when the Queen of England laid a sword on his shoulders—making him the first Tamil knight in half a century—he had already delivered something far more valuable than royal recognition: a revolution in maternal care that would save hundreds of thousands of lives.

His Maternity Dashboard, a colour-coded clinical warning system now mandated in every UK hospital, turns critical seconds into lifesaving action when a mother begins to bleed. His work on cardiotocography transformed fetal monitoring from educated guesswork into precise science. And the FIGO consensus guidelines he helped craft? They are the gold standard on every inhabited continent.

Yet between presidencies and protocols, he trained generations of obstetricians through 38 books, more than 290 publications, and over 500 lectures delivered worldwide.

Today, as Emeritus Professor at St. George's University of London and one of the most cited obstetricians alive, his legacy is not written in journals alone. It lives in the heartbeats of children who would not have survived without his protocols; in mothers who walked out of hospitals because a dashboard caught their bleeding in time.

His story is not just about medicine, or being Tamil, or defying odds.

It is about what becomes possible when brilliance refuses borders.

In this Jaffna Monitor exclusive, we reflect on Professor Sir Sabaratnam Arulkumaran’s remarkable journey—from the classrooms of Jaffna to the pinnacle of global medicine, and on how one man’s wisdom helped transform maternal care forever.

Could you share your early life in Jaffna — the schools you attended, your family background, and some of the formative memories from your childhood that have shaped who you are today?

My earliest memories of Jaffna go back to my time in Kantharmadam, where I first attended a small school known locally as Madathu Pallikoodam (மடத்துப் பள்ளிக் கூடம்) when I was about five or six years old. Before that, our family lived in Nattandiya, Puttalam, where my father worked as an engineer at the local glass factory.

Later, when my father joined the Marketing Department as an Assistant Commissioner, we relocated to Batticaloa, where we lived for four years. During that period, I studied at St. Michael’s College, Batticaloa.

Four years later, my father was transferred to Jaffna as Assistant Commissioner for Agrarian Services, and our family returned. I then joined Jaffna Central College in Grade 7, completed both my Junior and Senior School Certificate examinations (JAC and O/L) there, and later pursued my A/L studies at Mahajana College, Tellipalai.

From Mahajana College, I gained admission to study medicine at the University of Colombo in 1967.

How did your experiences living in Nattandiya, Batticaloa, and later Jaffna shape your outlook and contribute to the person you have become today?

My memories of Nattandiya are faint because I was very young, but I do recall the simplicity of our life there. We didn’t have toys, so I entertained myself with my father’s bicycle — I would place it on the stand and rotate the pedals for fun.

In Batticaloa, we lived on Lake Road. Those were lively years. Together with other children, I would go to the lagoon with a small fishing net — what we called a ‘tango’ — and catch fish just for fun. It was also in Batticaloa, at St. Michael’s College, which was run by American missionaries, that I was introduced to sports. They were enthusiastic about baseball and basketball, and that is where I first began playing basketball.

When we later moved to Jaffna, I joined Jaffna Central College in Grade 7 and continued playing basketball under the guidance of several excellent coaches, including Mr Nadarajah, Mr Arasalingam, and Mr Balasingam. I was very active in sports — basketball, athletics, and football.

Although I passed my O/L examinations, my father felt I was spending too much time on sports and not enough on studies. He transferred me to Mahajana College, which had a strong academic record. At Mahajana, I played hockey and badminton, and eventually focused on preparing for medical school.

Our family life in Jaffna was deeply rooted in faith. We regularly visited two temples in particular — Palanthoddam Pillaiyar Kovil and Nallur Temple on Friday mornings. We also prayed at the Veeramakali Amman Kovil in Nallur. My parents were very religious and instilled in us the belief that, with God’s grace, everything would fall into place.

Looking back, the influences that shaped my character and career were my parents’ guidance, my teachers’ discipline, and the values and way of life rooted in our religious upbringing.

Sir, how would you describe your belief system today — spiritual, religious, or God-fearing — and how has it evolved over time?

I was fortunate to have my father-in-law, Dr Muttuthamby, who was deeply religious and shaped much of my early understanding of faith. Through him, I learned the three pillars of religious practice: Bhakti Yoga, Karma Yoga, and Jnana Yoga.

Bhakti Yoga is devotion — going to the temple and praying.

Karma Yoga is dedicating your work and service to God and to humanity.

Jnana Yoga is learning and reflecting through texts like the Bhagavad Gita.

As life became busier, I naturally moved more towards Karma Yoga. My daily routine is very simple. I begin each morning with a brief five-minute prayer. I wear a chain with a Ganesha pendant, and as I leave for work, I tell myself that I am doing God’s work as His representative. At night, before going to bed, I pray again. I still go to the temple occasionally — so my Bhakti Yoga continues, even if in small, steady doses.

For Jnana Yoga, I listen to the Bhagavad Gita from time to time. But Karma Yoga remains my centre. I believe that our thoughts, our words, and our deeds must be good — and when practised consistently, they become who we are. To me, that is the essence of religion.

And I genuinely believe this: if I have one hour to spend, and the choice is between praying and serving others, then one hour of service is equal to one hour in the temple. That has been my guiding principle.

Sir, this profound understanding you have of religion—particularly Karma Yoga—has clearly shaped your worldview. In what ways has this philosophy influenced your career and your personal life?

Yes, as we go through life, our responsibilities change. I began as a doctor, then became a lecturer, professor, and later head of department — in fact, I headed three departments: one in Singapore, then in Nottingham, and later in London. In these roles, you have to manage large numbers of people — 80, 90, sometimes even 100 staff members. Naturally, mistakes happen, and problems arise. The challenge is how to deal with them fairly and impartially, helping the individuals involved while also ensuring that others do not suffer because of those mistakes. That balance is difficult, and I found that thoughtful religion helped me.

The Bhagavad Gita teaches this through the dialogue between Arjuna and Krishna. Krishna reminds him that even if the people involved are your own half-brothers, there are moments when you must still do what is necessary. That perspective helped me navigate difficult decisions when managing people, departments, and large organisations.

I served not only as a professor, but also as President of the Royal College, later President of the British Medical Association, and then President of the International Federation. In all these roles, I had to work with hundreds of people. Religion helped me reflect on how to decide: yes, something has gone wrong — but how do we guide, advise, or correct someone in a way that causes the least harm? How do we ensure accountability without breaking the rice bowl of the individual?

That balance — firmness with compassion — is where religion has always helped me.

In Jaffna, many parents are often hesitant to encourage their children to pursue sports. Yet you excelled in multiple sports and even captained the Jaffna Central College basketball team. Could you share how your sporting background—your discipline, competitiveness, and teamwork—shaped your professional life and contributed to the person you became?

Yes, I think teamwork — working together for the benefit of someone else — is the most important thing, just as it is in medicine. We have a consultant, junior doctors, nurses, attendants, and many others. We all work as a team. In front of the patient, everyone is equal. Everyone has to work seamlessly so that the patient receives the best possible care.

Teamwork in sports—whether in football or cricket—is similar. In football, for example, you may feel the urge to take the shot yourself. But at the same moment, you also have the instinct that if you pass the ball slightly to one side or the other, someone else may have a better chance of scoring for the sake of the team, not for your individual glory. That is how you learn teamwork.

Similarly, when someone else is the captain, you learn to follow the leader. If you disagree, you discuss it with the individual. But when the actual game starts, you pass the ball in a way that helps the team succeed. When the team gets the glory, you also share in it.

In medicine, it is the same. You may be the leader, but you have to identify who is the best person for each task and how best to coordinate everyone to achieve success for the patient.

This applies to all walks of life. Whether it is a hotel, a shop, or any workplace, there is always a leader and a team that must work together smoothly to deliver the best possible outcome for the customer.

What would be your advice to parents who still see sports as an obstacle rather than a constructive and essential part of a student’s development?

Parents need to understand — and students must also be reminded — that sports occupy only a limited number of hours in a day. The real issue is not the time spent playing, but the time wasted after the games are over. During my school days, we played from 4 to 6 p.m., which was perfectly reasonable. But what often happened afterwards was that students stayed back, chatted, wandered around, and lost valuable time before heading home.

So discipline is essential. Students should play their sport and then return home at the correct time to continue with their studies. That balance is what matters.

Parents must also recognise that not everyone will become a top-level athlete. We all must eventually find a livelihood. There may be one exceptional high jumper in Jaffna Central, for example, who can go further in sports, but many others may not reach that standard. Those who cannot should accept that reality and focus on their studies to secure a job. Parents worry because they want their children to study, become independent, and have a stable future.

Today, everyone studies science, but entering medicine — or any competitive field — depends on several factors: how much you study, how well you perform during exams, and sometimes even a bit of luck. Many elements come into play. What we can control is giving our best.

So parents should encourage both studies and sports. Not excessive emphasis on sports with less focus on academics, but a healthy, guided balance. Parents already emphasise studies because they worry about their children’s future — and rightly so in a competitive world. But with proper discipline, both sports and studies can complement each other and help a child grow holistically.

Do you still engage in sports? How important has sport or exercise been in helping you maintain your health?

Unfortunately, when I became a doctor — a house officer, then a lecturer, and so on — the work consumed so much of my time. I slowly stopped playing sports. In my 30s and 40s, I continued jogging and running, but later it became mostly walking exercises rather than playing any sport.

In obstetrics and gynaecology, emergencies can come at any time. When the hospital calls, you have to drop everything and go. Clinical doctors work from 9 to 5 and are then on call. And for academic doctors — lecturers, and teachers — you also have to do research, think about it, and read a lot of scientific papers. All of this takes a great deal of time.

So if one is not prepared to put in the number of hours needed to be an academic, they cannot excel. If you want to do well, you have to put in those hours, which means you must sacrifice something else. For me, that sacrifice was sport. I regret it in some ways, but I am also happy to be where I am because of that sacrifice.

Could you share your experiences from your days at the Colombo Medical School? What were those years like for you?

I was at Colombo Medical School from 1967 to 1972. During that time, I continued playing sports. I played basketball and eventually became the captain. I also played hockey and took part in inter-collegiate matches, and I played some rugby and football as well, though not at a major level, mainly as part of the team. My main focus in sports was hockey and basketball.

Academically, I passed all my examinations on the first attempt. In my final exam, I obtained a second-class, which was a great relief. Because of that, I was able to work in Colombo as an intern, first with the Professor of Paediatrics, and then with Dr Ganesan, an obstetrician from Jaffna who was working at Castle Street Hospital in Colombo.

These experiences gave me a strong foundation. Staying in Colombo allowed me to attend courses and prepare well, and I passed my primary FRCS. Later, before I left for the UK, I also completed my MRCOG Part 1 in 1978.

Sir, you spent a considerable period of your career in Singapore and were doing exceptionally well there. Could you share what those years were like and what led you to make the decision to move from Singapore to London?

I first left Sri Lanka in December 1978 to complete my FRCS, a surgical qualification, along with the MRCOG in obstetrics and gynaecology. I worked in the UK for three years, until March 1982, and then returned to Sri Lanka. I was very keen to pursue academic medicine and work in a university, so I approached the professors in Colombo, Kandy, Galle, and Jaffna.

At that time — and even now — university academic positions in Sri Lanka were very limited. In Jaffna, Professor Sivasooriyar was the only one who offered me a two-year position, as one of his lecturers had gone on sabbatical leave.

Meanwhile, I had applied for university posts abroad — in Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Nigeria, and several other places — through advertisements in the British Medical Journal. Singapore University called me for an interview, and I was offered the job. I joined as a lecturer, later became a senior lecturer, then an associate professor, then a professor, and eventually head of department. This progression was largely due to my substantial research and publishing, and I completed both my PhD and MD during that period.

So from 1982 to 1991, I continued to grow academically, and in 1993 I was appointed head of department. Around this time, family considerations became important. My eldest daughter was studying at the United World College in Norway and then moved to the UK to study medicine. My second child also wanted to pursue medicine and needed to do A-levels in London. My parents were living in London with my youngest brother, and my wife’s parents were also in London with her sister.

Although we were very happy in Singapore — and I held a good, permanent position — most of our close family were in London. I therefore explored opportunities in the UK and received interest from several universities, including Liverpool, Bristol, and Nottingham. Nottingham asked me to apply formally, and I applied and received the appointment. I served there for four years.

In 2001, St. George’s University of London invited me to apply for a professorship. I applied, was appointed, and I remained there until my retirement in 2013.

You are widely recognised for your significant contribution to reducing maternal mortality rates in the United Kingdom. Could you share how that journey unfolded, and what experiences and initiatives led to that achievement?

In the early 2000s — around 2001 to 2003 — there were ten maternal deaths at Northwick Park Hospital, in the northern part of London. Ten deaths in three years, out of roughly 15,000 deliveries, was extremely high — about six times the national average.

The Healthcare Commission, then chaired by Sir Ian Kennedy, even suggested that the hospital might need to be closed because it appeared unsafe for patients. But the hospital performed around 5,400 deliveries a year, so abruptly closing it was not practical. The government urgently needed a solution and approached me to help.

I went to the hospital and brought in a few consultants and senior midwifery staff from other hospitals to work there one day a week. We introduced what is known as clinical governance. Clinical governance involves ensuring adequate staffing, proper training, regular educational programmes, consistent audit activity, systematic review of complaints, and the use of a clinical dashboard to monitor key indicators.

Over the next 18 months, after implementing these systems in an organised way, we did not have a single maternal death. The Healthcare Commission then declared that the hospital had met the required standards and lifted it from special measures.

During that period, I was working at St. George’s Hospital two or three days a week, and at Northwick Park the remaining days, to bring about the changes needed.

A key part of this transformation was introducing what I called the maternity dashboard. Just like a car dashboard alerts you when fuel is low — turning orange or red — a clinical dashboard highlights when crucial parameters are drifting into unsafe zones. We monitored indicators such as maternal deaths, blood transfusions, and ICU admissions. Whenever a parameter rose above acceptable levels, it triggered immediate action: Was it due to staff shortages? Inadequate training? Gaps in knowledge? Lack of guidelines? We investigated and promptly rectified the issues.

The Royal College subsequently adopted the dashboard approach as well, recognising its effectiveness.

This structured introduction of clinical governance — and the use of the maternity dashboard to apply it consistently — was the reason I was recognised for contributing to the reduction of maternal mortality in the United Kingdom.

Where did you develop your administrative skills? Were they something you naturally possessed, or did you acquire them through experience and guidance?

There is a lot of literature available on how organisations function—whether in industry, large commercial companies, or public institutions. Any organisation must have a proper governance structure. Even in a country like our Parliament, there must be a functioning President, parliamentarians, defined rules, and a connection to the grassroots so that the people’s needs are met. The same principles apply to all fields, including health.

If clinical governance is properly followed and everyone performs their duties responsibly, nothing should go wrong. But in reality, systems fail. People get tired when overworked and make mistakes. Mental stress also contributes to errors. So we need to identify these issues early and rectify them before they become major problems.

You learn this by reading, by observing, and by studying how systems work elsewhere. For example, if clinical guidelines have not been updated for three years, they must be revised. But creating guidelines alone is not enough—you must train staff and educate them on how to use them. And even then, you don’t know whether they are being followed, so you need an audit process.

You audit the structure—whether the necessary resources are available.

You audit the process—whether people are actually doing what they are supposed to do.

And you audit the outcome—whether the guidelines have led to safe and effective practice.

You also study complaints that come to the hospital, because they reveal what is not functioning properly. You learn from your own unit when complaints arise. And you learn from reading about incidents in other hospitals or even in other industries—what went wrong and how it was corrected.

So the knowledge is available everywhere. The key is in knowing how to gather all these elements, bring them together, and apply them effectively in your own system.

Sir, do you believe the system you implemented in London could be effectively replicated in Sri Lankan hospitals?

Yes, I am sure it can be replicated. The system works when there is a clear leadership structure within each department and each hospital. It should function like a pyramid: the hospital’s medical director oversees all departments, and within each department—surgery, radiology, and so on—there must be someone responsible for monitoring the work.

That person must check whether there are enough staff, whether proper guidelines are in place, and whether the department is operating safely. They should produce a report at the end of each month.

This requires time—extra time—for the individual who takes on that responsibility. Such individuals can be designated as clinical directors and should be given at least half a day each week to oversee these aspects.

So yes, the system can be reproduced in Sri Lanka. It is certainly possible.

You have held several major leadership positions throughout your career. What key leadership lessons have you learned from those roles that Sri Lanka’s health administration could adopt?

I think the first and foremost requirement is that a leader must have the knowledge and experience necessary for the role. You must have the conviction that you can lead even before you apply for a leadership position. For example, if you are unsure whether to apply for a head clerk or a manager post, then you are not yet ready to be a manager. Conviction and confidence come only through knowledge and experience.

If you do not yet have sufficient knowledge or experience and your aim is to reach a leadership position, you must start preparing early—by learning and reading more and taking on smaller responsibilities before moving into larger roles. Leadership is not just knowledge; it is wisdom. And wisdom is knowledge plus experience.

When you reach that stage and apply for a senior position, you must assess the organisation—whether it is a company or a hospital. You must understand its workload, how many people are working, the problems it faces, and then develop a plan. Your plan should address the workforce, the infrastructure, the processes, and the outcomes you hope to achieve.

For example, when St. George’s University invited me to apply, I made six visits from Nottingham. One day, I met the administrators—the chief executive, medical director, and nursing director. Another day, I met clinicians; on another day, scientists. Every time I returned by train, I took notes: what could be improved, what changes were needed, what resources were required, and what the cost would be.

Planning is power. After studying the institution, I submitted a plan outlining what was happening, what needed to be done, and what additional resources—money, staff, or infrastructure—were necessary. If an organisation can meet at least 80% of those requirements, then it is worth joining. But if they say they can provide 0%—no funding, no staff, no support—then there is no point in taking the role, because you cannot execute the plan.

So planning is essential. Today, with websites and publicly available information, you can study an organisation’s structure, function, and performance beforehand. Using your knowledge and what you learn from the literature, you can work out how the organisation can improve. And when you go for the senior position, you must be ready to say: ‘This is what I will do, and this is how I will monitor it’.

As a senior and highly experienced medical professional, what do you consider to be the biggest obstacles or threats currently facing Sri Lanka’s healthcare system?

I think in any country, a medical system fails when the individuals working within it do not feel aligned with the system or do not feel that they are part of it. If every doctor simply follows the job description mechanically—coming at 9 a.m., doing clinics until noon, operating at 2 p.m., leaving at 6 p.m.—and does not engage in collective activities that strengthen the system, then the overall quality will decline.

There must be opportunities for shared learning. For example, there should be regular local meetings involving doctors, nurses, and attendants, selected and organised by the medical director. They could discuss issues such as delays in the emergency department, structural problems, or workflow challenges. This allows everyone to analyse what is going wrong and how it can be improved.

Time needs to be allocated for staff to improve their knowledge and understand what their colleagues in other units are facing. It is easy to criticise doctors or staff at a particular hospital—such as Jaffna Hospital—but when you sit with them and observe, you realise the realities: overwhelming patient numbers, difficult situations with patients, and staff being pulled away for other duties.

Only by studying these issues can we identify how to rectify them. That requires additional time and additional manpower. Without creating space for teamwork, shared responsibility, and system-wide dialogue, the medical system will struggle.

Sir, having observed societal change over five decades, do you feel Tamil women today are more empowered in making decisions about their health compared to earlier times?

Yes, I think so. Empowerment comes with education and independence. Today, if a woman has a menstrual problem or a pregnancy-related issue, she understands the situation much better. She can speak more freely about it. With a mobile phone, she can call a friend and discuss the issue; that friend may know someone with a similar experience. She can also search on Google or other social media platforms to learn more.

She can then discuss what she has understood with her husband or partner, or with her parents if she is unmarried. Because she is better informed and more independent, she can also find the resources she needs more easily than before. She is no longer entirely dependent on someone else to take her to the hospital. If public transport improves, that empowers her even further.

So, the improvement has been gradual, but it is real. With advances in technology, communication, transport, and access to knowledge, women today are far more empowered to seek and receive the treatment they deserve.

With the rise of AI-assisted telemedicine and digital health technologies, how do you envision the field of medicine—particularly your speciality—evolving in the coming decades due to advancements in artificial intelligence?

The future of artificial intelligence in medicine will depend on what I call the three Ds: data, digital, and devices. First, we convert information—data—into a digital form. Once digitised, computers can use AI to analyse it, build decision trees, and guide patients by suggesting possible problems and asking relevant questions. In this way, the system can be fine-tuned so that data, digital platforms, and devices all work together to support diagnosis and management.

We already see this in practice. For example, people now use continuous glucose monitoring patches for diabetes. These devices provide minute-to-minute readings of blood sugar levels, unlike the traditional method of pricking the finger three times a day, which many people dislike and therefore avoid. With continuous data, individuals can see exactly where their blood sugar stands and make informed decisions, such as avoiding ice cream when their glucose is high. This is a simple form of AI-assisted feedback.

AI systems will also integrate multiple clinical parameters, such as renal function tests, and provide looped information—for instance, alerting the patient or clinician if something may affect kidney function.

AI has already been introduced in screening programmes. In breast cancer screening, for example, radiologists may get tired after reading many X-rays in a day. A computer can analyse the images, detect abnormalities, and highlight areas of concern. The same applies to cervical cytology.

So, the biggest advances will come in screening and repetitive tasks, where AI can support accuracy, reduce fatigue-related errors, and improve early detection.

Sri Lanka is often seen as not being ready for private medical education, as previous attempts to establish private medical universities faced strong opposition from medical students and the GMOA. What is your perspective on this issue? Do you believe Sri Lanka needs private medical education?

Yes, Sri Lanka must have private medical education — and the public mindset must change regarding it. If you drive through Colombo, you will see many semi-universities and technical colleges offering BSc degrees in accountancy, business management, and other fields. But there is nothing comparable for medical education. This is largely because, in many countries—including Canada, Australia, and the United States—the medical fraternity tends to protect the profession. That mindset has to change.

As you mentioned, many Sri Lankan students who go abroad to study medicine are actually well qualified. They often fail to enter local universities, not because of poor grades, but due to quota systems or other selection criteria. Their parents are forced to make enormous sacrifices—selling property, taking loans—to send them overseas. As a result, the country loses a huge amount of foreign exchange.

If Sri Lanka develops private medical schools, we can retain these students locally. And there is another major angle: global demand. For example, the United States alone is projected to need around 130,000 additional doctors by 2035. If Sri Lanka produces more doctors, many can work abroad, earn well, and send foreign exchange back home.

There is also potential to attract international students. I am currently a professor at the University of Nicosia—a private university linked to St. George’s University of London. Students come from Oman, Norway, Australia, America, Singapore, Malaysia, and many other countries. All of this generates substantial income for Cyprus. Sri Lanka could do the same.

Private medical education would also boost employment. Medical schools require additional lecturers, consultants, and support staff. If there are 100 students, there must be hostels, catering services, administrative support, and clinical placements. All of this creates jobs.

Furthermore, when teaching hospitals have students, the quality of medical care naturally improves. Consultants must be more accountable because students will question clinical decisions. This raises standards throughout the system.

If private medical schools admit international students, they bring foreign exchange—in tuition fees alone, typically 30,000 to 40,000 USD per year. Beyond that, their living expenses—housing, food, travel—are all spent within the country. So Sri Lanka not only prevents the loss of foreign exchange from its own students going abroad, but also gains new foreign income.

It is disappointing that private medical education is still not encouraged in Sri Lanka, especially when private institutions already exist for engineering, commerce, business administration, accountancy, and many other fields. Medical education should not be the exception.

Sir, why do you think there is such strong opposition to private medical education in Sri Lanka? What drives these protests—misconceptions, insecurity, or organised influence? In your view, who or what is motivating this resistance?

I think the main reason is that medical students fear increased competition. If private medical schools are established and Sri Lankan students enrol, they will later compete for the same jobs. But this competition is already underway—students returning from places like Bangladesh and Russia also compete for positions.

The second issue is the belief that medical education should be provided only to local students, rather than admitting international students. This competitive mindset creates a problem. Without international students paying fees, it becomes difficult for a private medical school to sustain itself financially.

A practical solution would be to operate a private medical school that admits international students—because they pay higher fees—but reserves 10% or 20% of its places for local students through scholarships. This way, the revenue from international students can subsidise opportunities for Sri Lankans.

There are workable ways to introduce private medical education that benefit not only Sri Lanka but also students from other countries.

I don’t want to create any controversy, but I would like to ask: Do you think Sri Lankan medical students are somewhat insecure?

I think so. The students and the GMOA—the Government Medical Officers’ Association—are the ones who protest. They need to re-examine the entire issue. They may give various reasons, but the simple question remains: if countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Cyprus can have private medical schools, why not Sri Lanka?

Private medical education can generate foreign exchange, prevent outflows of funds, and attract foreign students. For example, consider a hospital in Vavuniya and the surrounding areas. There are many unemployed young people—both boys and girls—who could gain profitable employment if 100 or 200 students came to study there for five years. If those students are foreign, they bring foreign exchange into the local economy.

The local medical students and the GMOA might argue that private medical schools should admit only foreign students. That is one option. However, once that is proposed, others in Sri Lanka will ask: why allow education for foreigners but not for our own students?

The reality is that those who invest the capital to establish a private medical school will not do so unless there is some return. There must be revenue to sustain the institution.

In places like Gampaha, Vavuniya, and Kilinochchi, establishing medical schools would create jobs and stimulate local economies. Students spend two years learning basic sciences and three years in clinical sciences. Clinical learning comes from patients. In these cities, there are patients, but they are not being utilised for teaching or for improving care.

Improvement would be visible not only in clinical outcomes but also in day-to-day operations. For example, if a patient needs overnight monitoring and there are only two nurses for an entire ward, it becomes difficult to arrange. But medical students can help with simple tasks as part of their learning, while also supporting patient care.

So the student workforce can be used both for their education and to strengthen the healthcare system.

Only a handful of Sri Lankan Tamils — from Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan and Sir Arunachalam Mahadeva to Sir Kanthiah Vaithianathan — have ever been honoured with a knighthood, and no Sri Lankan Tamil received this title after 1952. In 2009, you became the first Sri Lankan Tamil in more than half a century to be appointed a Knight Bachelor. What does this recognition mean to you personally, and how do you see it in the wider journey of our community?

It means a great deal to me, because the honours system in the United Kingdom is structured in a pyramidal way. Every six months, national honours are announced. At the very top are about 20 individuals who receive knighthoods or damehoods—men are appointed Knights Bachelor (and receive the title ‘Sir’), while women are appointed Dames.

Below that level, as the pyramid expands, around 60 people are appointed Commanders of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). Then about 100 are appointed Officers of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), and roughly 300 are appointed Members of the Order of the British Empire (MBE). So the structure is broad at the base and narrow at the top.

To be selected for the highest category is a rigorous process. Nominations are reviewed by specialist committees—such as the Committee for Sport, the Committee for Philanthropy, the Committee for Education, the Committee for Medicine, and the Committee for Science. These committees consist of highly respected individuals. One cannot nominate oneself; someone else must nominate you. I don't know who nominated me, but that is how the system works.

Each committee recommends a small number of names—for example, five from medicine, five from sports, five from philanthropy—which they believe deserve recognition. These recommendations are then forwarded to a higher-level honours committee comprising the chairs of all the committees and senior officials. This group further filters and decides: for instance, out of the five names recommended for knighthood, perhaps only two will be selected; the rest may be awarded CBEs or OBEs.

It is a rigorous and competitive selection process. For example, David Beckham received an OBE many years ago while he was captain of the England football team. But he was awarded a knighthood only recently—in June—because of his 20 to 30 years of philanthropic work, supporting children, communities, and charitable causes. Knighthoods are awarded not just for professional excellence, but for long-term contributions to society.

So, receiving a knighthood is a distinguished honour. Being given the title ‘Sir’ is a significant recognition, and I am deeply grateful for it.