“The way for emancipation is to renounce language pride, national pride, religious pride, and caste pride.” – Periyar.

Neelan Tiruchelvam – Unsilenced

Directed by peace activist and filmmaker Pitasanna Shanmugathas, Unsilenced revisits the life and assassination of one of Sri Lanka’s most courageous liberal thinkers. The documentary traces Neelan’s relentless commitment to pluralism, constitutional reform, and democratic values at a time when both state repression and militant authoritarianism left little room for dissent. Through a powerful mix of interviews with academics, activists, and political leaders—woven together with archival footage—it captures the alternatives Neelan put forward to Sri Lanka’s ethnocratic state, especially his bold 1995 draft for devolution, and the tragic consequences of its rejection.

Filmmaker Pitasanna Shanmugathas, director of the documentary Neelan: Unsilenced

Far from a conventional biography, Unsilenced portrays Neelan as a bridge-builder—someone who believed in dialogue over violence and who embodied the democratic possibilities that Sri Lanka turned away from. At a moment when the country once again grapples with constitutional reform, the film challenges us to confront a haunting question: what if his vision had been embraced?

Born into a politically active family, Neelan was shaped by both law and activism. His father, M. Tiruchelvam, was a lawyer and leader in the Federal Party; his mother devoted herself to social causes. After studying law at the University of Colombo and Harvard, Neelan entered politics amid a deepening ethnic crisis. Elected as a TULF MP in 1982, he quickly earned international respect as a constitutional expert and an uncompromising advocate of democracy and human rights.

Unsilenced opens with searing images from the final stages of the 2009 war—bombings that claimed tens of thousands of civilian lives. It forces viewers to consider whether the war’s catastrophic end might have been avoided had Neelan’s pluralist blueprint been taken seriously a decade earlier.

The film explores the arc of post-colonial Sri Lanka: the rise of majoritarian nation-building, the steady erosion of minority rights, and the violent cycle of state repression and militant retaliation. Against this backdrop, Neelan’s vision emerges as a striking alternative—an insistence that peace required not domination, but shared power.

By foregrounding his legal imagination, philosophical depth, and unwavering faith in democratic solutions, Unsilenced reminds us that Neelan was more than a constitutional scholar. He was a champion of both individual and collective rights, a believer in pluralism at a time of polarisation, and above all, a reminder of paths not taken—but still within reach.

Neelan’s Role in Kazakhstan’s Constitutional Journey

After Kazakhstan declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Neelan joined an international consultancy team to assist in drafting its new constitution. It was remarkable that, when examining the country’s multi-ethnic composition, he chose not to debate the semantics of federalism but instead adopted a pragmatic, people-centred approach. In Unsilenced, law expert Steve Kanter, a fellow consultant, notes that Kazakhstan’s experts had already produced an impressive draft constitution, and the team’s role was to advise and recommend. With Kazakhs and Russians each comprising 40% of the population, and groups such as Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Germans making up the remaining 20%, concerns arose that federalism could lead to ethnic enclaves. Neelan emphasised safeguarding political, individual, religious, and language rights for all, while promoting local decision-making within a unitary state. Most of these proposals were accepted, reflecting his vision of equal rights for every citizen, regardless of ethnic or religious background.

Neelan in Chile: Parallels of Power and Repression

He was also an observer of the 1988 plebiscite in Chile. The Chilean example is relevant to Sri Lanka because, four years after Pinochet’s coup, a semi-dictatorship was established by J.R. Jayawardena of the United National Party. Under the new constitution, the executive presidency was given enormous power. Trade union rights were suppressed, political opposition was crushed, and violence against Tamils was perpetrated by the state. Tellingly, both Pinochet and Jayawardena were ideologically committed to neoliberalism and dictatorship.

A True Liberal

Dr. Neelan Tiruchelvam

As Vasuki Nesaiah commented in unsilenced , Neelan was not from a leftist tradition but a true liberal, convinced that Sri Lanka’s multi-religious and multi-ethnic character should be recognised in both its constitution and practice. But where the liberal invests excessive importance in procedural design and instruments, Neelan understood that merely changing the constitution was insufficient without challenging majoritarian discourse. An intellectual movement was also necessary to promote pluralism, democracy, and human rights. This was why he established the International Centre for Ethnic Studies in 1982 in Colombo, encouraging debates and sponsoring publications.

However, in Unsilenced, there is a conspicuous absence of Sithie Tiruchelvam’s contributions. The late Sithie Tiruchelvam, an attorney-at-law, was not only the wife of Neelan but was also actively involved with the Nadesan Centre for Human Rights, South Asians for Human Rights, and the Family Rehabilitation Centre. She was a founding member of Foundations for Peace and the Neelan Tiruchelvam Trust.

Unsilenced would have been a complete documentary if Sithie Tiruchelvam’s active role had been acknowledged.

The Background of the 1995 Proposals

Neelan’s August 1995 draft for constitutional reform was historic, as it acknowledged Sri Lanka’s multi-ethnic character. While the unitary state embodied Sinhala majoritarianism, his idea of a “Union of Regions” offered a bold alternative.

President Chandrika Kumaratunga, elected in 1994 on a peace mandate, promised to abolish the executive presidency and reached out to the LTTE. Talks began in October 1994, and a ceasefire was signed in January 1995. Before the fourth round, however, the LTTE demanded: the removal of the Jaffna embargo, lifting of the fishing ban, dismantling of Pooneryn camp, and free movement in the East. The government conceded the first two and agreed to review the rest, yet the LTTE abruptly walked out in April, sinking two navy gunboats the next day.

The war resumed, and amid renewed hostilities the government unveiled its reform plan. Though fighting had not yet escalated into full-scale war, by October 1995 the army had captured Jaffna, forcing the LTTE into Vanni. The Tigers rejected the proposal outright, claiming they were excluded from consultation. Adele Ann, writing in Tamil Nation, argued that offering proposals while pursuing military action undermined their credibility and that only the LTTE truly represented Tamil aspirations. Similar points were echoed by Prabhakaran and Balasingam, as shown in Unsilenced.

Yet this critique ignored the LTTE’s unilateral withdrawal and return to war. Had they truly sought peace, they could have tested the proposal under a ceasefire. As Packiyasothy Saravanamuthu notes in the film, if Prabhakaran had been sincere, he should have engaged with the proposal rather than rejecting it outright. Sinhala nationalists, meanwhile, condemned the proposals as separatist, and the PA government lacked a two-thirds majority to pass them. Still, Chandrika’s acknowledgment of minority discrimination marked a rare shift in southern politics—an opening for dialogue.

The proposals differed sharply from the 13th Amendment under the 1987 Indo-Lanka Accord, which left power with the centre. Moderate Tamil nationalists welcomed Neelan’s draft, but the LTTE branded him the chief architect and thus a “traitor.”

The film builds toward Neelan’s assassination by an LTTE suicide bomber. The irony is searing: Neelan never condoned state brutality, consistently opposed military solutions, and urged a democratic, pluralistic path. But the LTTE, a militaristic and authoritarian force, depended on absolute control and an ethnically pure vision. Negotiated settlements threatened their very existence.

Neelan acknowledged that counter-violence to state violence was inevitable, observing that “the AK-47 became the answer” to oppression. Yet he did not endorse violence—he merely identified its origins. He also pointed out the state’s failure to engage moderate Tamil leaders, especially in October 1983, when the TULF was forced to renounce separatism under the Sixth Amendment and as a result , they resigned their seats. This created space for Tamil militants to dominate the political landscape.

Brutality and Counter-Violence

In The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon describes counter-violence as a “cleansing force,” restoring dignity and self-confidence to the colonized. Yet he also warned that brutality, if unchecked, becomes anti-revolutionary and ‘a persistent battle has to be waged to prevent the party from becoming a compliant instrument in the hands of a leader’.

The LTTE’s authoritarianist trajectory embodied this warning. Once a small guerrilla force, it initially used suicide attacks against military targets—a tactic understandable for a numerically weaker army lacking sophisticated weapons. But as the LTTE grew into a conventional force with modern weaponry, its suicide missions expanded beyond the battlefield. They became tools for eliminating perceived traitors and political opponents: President Premadasa, Gamini Dissanayake, and even former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi were killed by LTTE suicide bombers. Civilians too became victims—in attacks like the Fort railway station massacre and the Central Bank bombing—while northern Muslims were massacred and driven from their homes.

At this point, the line between resistance and brutality collapsed. Suicide bombings against individuals stripped the struggle of its humanity and liberationist promise. As Rajani Thiranagama warned in Broken Palmyra (1989), the Tigers’ “intolerance, fanatical dedication, and lack of political creativity” would doom them, leaving only a legacy “smeared with the blood and tears of victims of their own misdoings.” Her prophecy proved chillingly accurate.

Of course, state forces were equally guilty of massacres, torture, and genocidal assaults—especially in the war’s final phases. But the LTTE mirrored that brutality. Counter-violence decayed into sheer brutality , reducing both perpetrator and victim to casualties of a narrow, exclusivist nationalism.

Neelan’s assassination, so poignantly depicted in Unsilenced, epitomises this degeneration. It cannot be phrased as counter- violence against the state violence but simply a brutality in its essence.

Colonial and Post-Colonial Context

Fanon’s reflections on violence were rooted in colonialism, where European powers conquered and ruled through racial hierarchies. In Sri Lanka, independence came not through a liberation struggle but as a transfer of power, leaving colonial structures largely intact.

Colonial rule classified people by race, embedding divisions in censuses and communal representation. After independence, these taxonomies were reworked into Sinhala majoritarianism and Tamil nationalism—two exclusivist ideologies. Sinhala nationalism exalted Buddhist hegemony and the glory of Sinhala kings, while Tamil nationalism cast itself as ancient and unchanging. Both discourses hardened ethnic boundaries.

Unlike colonial exploitation, which drained resources to the metropolis, post-colonial politics was controlled by local elites—mainly dominant caste landlords and elites groomed under colonial rule. The British education system, designed to train bilingual clerks, disproportionately benefited these elites. Schools in Colombo, Galle, and Jaffna produced large numbers of government servants, often from dominant castes. Tamils were later branded as colonial beneficiaries, a label that obscured how privilege was caste- and class-based, not simply ethnic.

This inheritance shaped post-independence politics. State-led ethnocracy and Tamil nationalism fed off each other, producing mutually exclusive identities. The nation-state curtailed minority participation, while Tamil nationalism hardened into authoritarianism, intolerance of dissent, and a cult of ethnic purity. Within this logic, anyone offering alternative solutions became a “traitor.”

In my article on Duraippah’s political murder, I analyzed the history of the “traitor” discourse in Tamil nationalist politics. The idea of eliminating “traitors” was deeply rooted in Tamil nationalism, with various militant groups, including the LTTE, targeting such figures during the 1970s and early 1980s. After 1986, Prabhakaran and the LTTE asserted sole leadership of the Tamil national struggle, equating dissent with treachery and normalizing the killing of so-called “traitors.”

After Neelan’s 1995 proposal was unveiled, the LTTE unleashed a campaign to discredit him, branding him a stooge of the state. Tamil media in LTTE-controlled areas blacked out the proposals, and fear kept dissenting voices silent. In Unsilenced, pro-LTTE propagandist Elavendan goes further, portraying Neelan as a collaborator and implying he was a traitor—revealing how deeply the discourse of “betrayal” had seeped into the ethno-nationalist imagination.

.

Others in the film challenge this framing. Journalist Ignasious Selliah recalls how Tamil media erased the proposals and vilified Neelan at home and abroad. Academic Sharika Thiranagama argues that since the LTTE never pursued a democratic path, being labelled a “traitor” by them should in fact be seen as a badge of honour. Politician Sumanthiran dismantles the very notion of “traitor,” noting how it justified the killings of Amirthalingam, Neelan, and others who had devoted their lives to the Tamil cause. He points out that Neelan was condemned with this label both before and after his death. Poet Cheran adds that no organisation resembling the LTTE has ever shown a genuine commitment to democracy.

Through these voices, Unsilenced reveals how the LTTE weaponised the “traitor” discourse —not only to silence critics, but to eliminate those who dared to imagine democratic alternatives.

The 1995 Proposal and Its Relevance

Minority protection, often claimed under the 1946 Constitution, was little more than a façade. From the outset, Sri Lanka’s state formation rested on a majoritarian, ethnocratic model rather than on equal political and civil rights. The 1972 Constitution deepened this imbalance by stripping away safeguards without resistance from the south. As Hannah Arendt observed, “The nation has conquered the state”—national sovereignty prevailed over citizens’ rights.

This reality was starkly revealed in the 1948–49 Citizenship Acts, which rendered the Malayaga Tamils stateless. In Mudanayake v. Sivagnanasundaram, the Privy Council—the highest judicial body in the UK for colonies and post colonies , which retained jurisdiction in Sri Lanka until 1972—upheld state sovereignty, thereby legitimising their disenfranchisement. Nation-building, in effect, extended colonial racial categories instead of dismantling them.

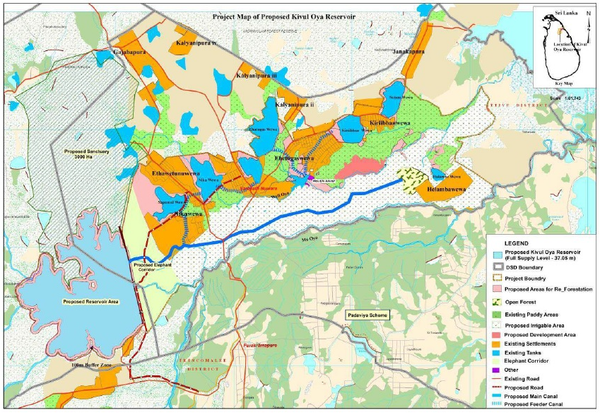

Neelan’s draft proposal of 3 August 1995 broke decisively with this legacy. It shifted the focus from ethnicity, homeland, and nationhood to universal guarantees of identity, culture, language, and religion for all communities. It replaced the unitary state with a “Union of Regions,” devolving real authority over land, policing, and education. Most significantly, it transferred centralised legislative powers to the regions, embedding pluralist democracy and participation at national, regional, and local levels.

Colonial provinces themselves were arbitrary creations—the British first carved three, later expanding to nine for administrative convenience. Their boundaries were never sacred. Under the 1987 Indo–Lanka Accord, the North and East were merged temporarily, subject to a referendum. Neelan’s 1995 draft suggested re-demarcating the North-East “in full consultation, with a view to reconciling Sinhala, Tamil, and Muslim interests.”

He also paid careful attention to Muslim concerns, proposing that Amparai could either form a separate Muslim-majority region or merge with Uva via referendum. While pragmatic, this revealed a tension: the overall proposal sought pluralist power-sharing, yet the treatment of the North-East risked reinforcing ethnic enclaves—a fragile and potentially unsustainable path.

In The Devolution Debate (ICES), Neelan argued that “territoriality” was the foundation for any meaningful scheme:

“The principle of territoriality in a way reinforces the pluralistic character of Sri Lankan society… Through the territorial principle, we are able to look at alternative ways of sharing power with which most of the people of Sri Lanka would be quite comfortable.”

Today, merging the North and East is politically unrealistic. Any new demarcation must therefore balance territorial realities with the political, social, and economic interests of all communities. As I noted in my article Need for an Epistemological Break: while resisting Sinhalisation and Buddhisisation is crucial, autonomy for the North and East must be rearticulated in regional—not ethnic—terms. Only then can devolution avoid exclusivity and foster genuine pluralism.

Unsilenced and Unfinished: Why 1995 Could Guide 2025

Unsilenced could not be more timely.

The fundamental principles that emerged from the Aragalaya—people’s democracy, social justice, and an inclusive political vision for Sri Lanka’s future—have redefined the national conversation.

This new mode of thinking was articulated in the NPP’s election manifesto, which secured victory on the pledge to abolish the executive presidency and establish an inclusive constitutional order. Unsilenced reminds us of an earlier vision that was never realised. Neelan’s 1995 proposal, bold in its pluralism and commitment to shared power, offers not merely a historical reference but a blueprint. To revisit it now would be more than constitutional housekeeping—it would be a tribute to Neelan and to all those who gave their lives for a democratic, pluralist future.

Note: Opinion pieces appearing in Jaffna Monitor represent solely the views of their respective authors and should not be construed as reflecting the editorial position of the magazine.