Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake says his government must convince the country — and the world — that Sri Lanka still has “a sustainable future” as it rebuilds from Cyclone Ditwah while emerging from a historic debt crisis and managing intensifying geopolitical competition in the Indian Ocean.

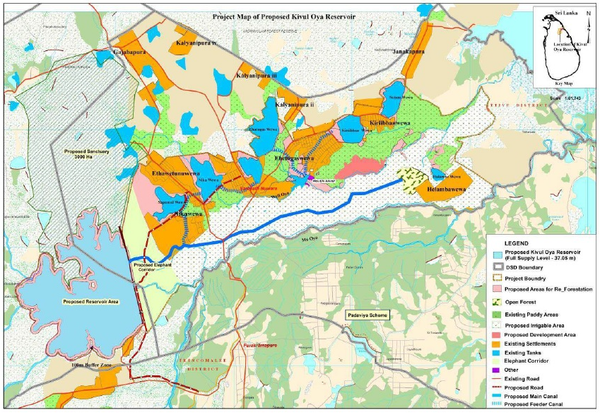

In a rare and wide-ranging interview with Newsweek at the Presidential Secretariat in Colombo, Dissanayake described Ditwah as “catastrophic,” hitting just as Sri Lanka concluded a US$25 billion debt restructuring that wiped more than US$3 billion off its books. The storm, he said, has set back an already fragile recovery, destroying tens of thousands of homes and inundating more than 273,000 acres of paddy fields.

The interview did not go unnoticed among local journalists. Dissanayake, who is famously reluctant to sit for extended, probing interviews with Sri Lankan media, appeared far more at ease granting one to a major U.S. publication. “Maybe the questions sound softer in an American accent,” a veteran reporter joked.

“We can’t impose austerity on people who have lost everything,” the president said, pledging continued subsidies for essential medicines, fuel and basic food items, alongside targeted cash transfers and large-scale assistance to rebuild homes, schools, hospitals and public infrastructure.

Debt, IMF and climate “trap”

With public debt still above 100 percent of GDP, Dissanayake acknowledged that Sri Lanka is trying to rebuild while working within an International Monetary Fund programme — a programme his own party had vehemently opposed while in opposition. As one political observer noted dryly, “Saying things is one thing; governing is another. It’s a bit like marriage — before the wedding, you can promise the world, but afterwards, you’re lucky if you manage the grocery bill. In politics, too, romance ends, and real expenses begin.”

The President also warned that climate-vulnerable countries like Sri Lanka are caught in a “trap,” where every flood, cyclone or drought erases years of development gains. But he avoided addressing the government’s own role in worsening Ditwah’s impact — most notably the abrupt opening of dam sluice gates that sent torrents of water through already-flooded towns, destroying homes and livelihoods and causing losses worth crores of rupees.

“This trap is not of our own making,” he said, arguing that global debt-sustainability frameworks must be redesigned for countries repeatedly hit by climate shocks.

Dissanayake said the government’s immediate priorities include constructing flood-resistant housing, restoring agriculture by providing seeds and equipment to affected farmers, and using infrastructure repair as a source of employment in devastated districts.

Balancing India, China and the U.S.

On foreign policy, Dissanayake maintained that Sri Lanka retains strategic autonomy despite being situated at the heart of the India–China–U.S. rivalry. His language was carefully calibrated, offering no hint of preference as he navigated the competing interests of all three powers — a diplomatic tightrope that analysts say he walked with the concentration of a child learning balance.

He described India, which he called a “civilizational connection” and Sri Lanka’s first responder in crises, as the country’s largest trading partner, top tourism source, and a major investor. China, he said, remains a “close and strategic partner” with deep trade and infrastructure ties. The United States, meanwhile, continues to be Sri Lanka’s largest export market and a key democratic partner.

“We don’t look at our relations with these important countries as balancing,” he said. “We work with everyone, but always with a single purpose – a better world for Sri Lankans, in a better world for all.”

Yet, as one political commentator observed, Dissanayake’s responses were so evenly distributed across all three capitals that he repeatedly had to insist he was not balancing.

Display of Sri Lankan political gymnastics

In a familiar display of Sri Lankan political gymnastics, the President used the interview to walk back warnings he himself had made before coming to power — including his earlier claim that the Chinese-run Hambantota Port posed a national security threat. Now, he characterises the 99-year lease as “commercial, not military,” stressing that the Sri Lankan Navy and Customs continue to maintain operational control. Port City Colombo, he added, is simply a commercial venture that must be monitored to ensure compliance with domestic law and the protection of sovereignty.

What he did not acknowledge is that his own party had vigorously opposed both projects while in opposition, branding them as assaults on sovereignty and classic cases of “debt-trap diplomacy.” Today, from the vantage point of government, the same projects appear far more palatable.

Disaster management overhaul

The President conceded that Cyclone Ditwah exposed deep weaknesses in Sri Lanka’s disaster-preparedness architecture — from early-warning systems and land-use enforcement to the basic speed at which relief reached affected communities. He announced plans to overhaul the National Disaster Management Authority with “real resources and authority,” expand radar coverage, pre-position equipment in high-risk districts, and map landslide-prone zones across the central highlands.

“With climate change, destruction of this scale should have been expected,” he said, acknowledging that Sri Lanka had “failed to prepare adequately” for years. He pledged that the government, working with international partners, would build “effective, efficient and accountable systems” and “rebuild Sri Lanka, better than it was before.”

But his interview avoided addressing the government’s own role in amplifying Ditwah’s devastation. Authorities failed to issue timely warnings despite clear forecasts from India’s Meteorological Department, the BBC and regional experts. Confusion from local officials continued almost until landfall, with some insisting “there is no cyclone” even as winds intensified. The abrupt opening of multiple dam sluice gates without proper evacuation alerts sent torrents of water into already-flooded towns, destroying homes that had survived the storm. Poor coordination between irrigation officials, disaster units, police and local councils left boats idle while flood-stranded residents pleaded for rescue. Hospitals reported delays in evacuating vulnerable patients, and relief convoys carrying dry rations and medical supplies donated by the public were stalled for hours because no government officer was available to sign acceptance forms

None of these failures featured in the President’s account. Not the contradictory messaging, not the dam-gate disaster, and not the bureaucratic paralysis that transformed a natural calamity into a man-made one. As one Jaffna resident put it: “Ditwah came from the sky, but half the destruction came from Colombo.”

Investment, transparency and corruption

Responding to concerns that revisiting major investment deals could unsettle foreign investors, Dissanayake argued Sri Lanka is building a cleaner and more predictable investment climate, not a hostile one.

He outlined a single-window approval system, a forthcoming Investment Protection Act, digital procurement, mandatory asset declarations and independent oversight. Every major project, he said, will face rule-based scrutiny on environmental standards, climate resilience, economic viability, technology transfer, labour protection and alignment with national development goals.

“Foreign investors want three things: clarity, consistency and confidence,” he said, promising “no special treatment for insiders or politically connected groups.”

Rights, security laws and transitional justice

Pressed on Sri Lanka’s controversial security laws – the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and the restrictive Online Safety Act – Dissanayake conceded that they have been used “as tools of repression” and are “out of place in a democracy.”

He pledged to repeal and replace the PTA with legislation closer to international human-rights standards, promising an end to indefinite detention, stronger judicial oversight, and guaranteed access to legal counsel.

But what he did not mention is that his own government continues to use the very PTA he condemns. Former Eastern Province Chief Minister Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan (Pillayan) remains imprisoned under PTA provisions — a decision that required and received Dissanayake’s approval as Defence Minister.

The Online Safety Act, he said, will be rewritten to focus on genuine harms such as incitement to violence and child exploitation, not criticism of the government.

“Trust is earned through action,” he said, noting that his administration is releasing political prisoners, reviewing dubious cases, and allowing space for peaceful protest while working on legislative reforms.

But noticeably absent was any mention of the government’s increasingly heavy-handed approach toward trade unions — especially those not considered friendly to the JVP–NPP. Several unions have complained of intimidation, sudden transfers, and administrative interference whenever they speak out.

Youth, migration and the future

With more than 300,000 Sri Lankans leaving for foreign employment in 2024 and youth unemployment above 20 percent, the president said the state must make staying in Sri Lanka “a competitive choice and not a sacrifice” for talented young people.

He promised reforms to build a more merit-based system, an entrepreneurship-friendly environment, better salaries and skills training, and stronger links between the domestic and global economy. At the same time, he said, the government will court the diaspora as a long-term development partner.

“Our biggest challenge,” Dissanayake concluded, “is achieving sustainable and equitable development while dealing with overlapping crises.” The task now, he added, is to convince both Sri Lankans and the world that the country can withstand climate disasters, escape the boom-and-bust cycle of crisis, and offer “a future worth staying for” to the next generation.