Historical Context and Religious Co-existence

According to Professor Ellawala in Social History of Early Ceylon, the conditions of pre-Buddhist Ceylon mirrored those of contemporary India. He suggests that due to this proximity, the people of Ceylon likely adopted forms of worship such as Saivism, which existed alongside Brahmanism [1]. With the subsequent spread of Buddhism to the villages, Buddhist viharas were often established near earlier Hindu shrines, symbolizing a long-standing tradition of religious co-existence that continues to define the region.

Early Historical Patronage

The history of the shrine at Kataragama (Katirkamam) is interwoven with the lineage of Sinhalese kings. King Mahanaga, the brother of Devanam-Piyatissa, left Anuradhapura after losing his kingdom to South Indian invaders and established his rule in the present-day Uva province. Circa 300 B.C., he built the Kiri Vihara at Kataragama, located roughly a third of a mile from the shrine of Murukan.

Mahanaga’s descendants remained in the Uva Province until the time of King Dutugemunu (161–137 B.C.), who was determined from childhood to regain the lost kingdom from foreign rule. He was directed to invoke the grace of Skanda, and the Skanda Upada details the vow he made at Kataragama to defeat King Elara [2]. Upon his victory, Dutugemunu made great endowments to the Skanda temple.

Literary Sources and Tamil Tradition

Reconstructing the history of the Murukan shrine relies heavily on literary sources. Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam’s work, The Worship of Muruka or Skanda, notes that there are over twenty literary compositions in Tamil sung in praise of the Katiraimalai-k-Kantan [3].

When exploring the rich tapestry of Tamil literature concerning Katirgamam, the hymns of the sage Arunakirinatar emerge as indisputably the oldest records. Dating back to the 15th century AD, these poetic verses offer a clear window into the past, demonstrating that Katirkamam was already widely celebrated among the Saivites of South India as a sanctuary for pilgrims and a principal center of the Skanda-Murukan cult [4]. Within the celebrated Tiruppukal of Arunakirinatar, sixteen specific verses are dedicated to Katirkamam.

Other significant literary works include Kadiramalaip-pallu, a 16th-century literary work that provides historical facts regarding temple constructions and the sage Kalyangiri (specifically verses 71, 72, and 103) [5].

The Siddha Tradition and the Legacy of Bhogar

Integral to the spiritual landscape of the Murugan tradition is the legacy of the Tamil Siddhas, particularly the great yogi and alchemist Boghar (also spelt Bhogar). In the wider Tamil spiritual landscape, the temples of Palani (Tamil Nadu, India) and Kataragama (Sri Lanka) are deeply linked, functioning as twin nodes of power on a single spiritual grid. This connection is forged through the life and works of Bhogar.

At Palani, home to the famous Dhandayuthapani Swamy Temple, Bhogar is recognized as the architect of the temple’s principal deity. According to T.N. Ganapathy in The Yoga of Siddha Bhogar, Bhogar is credited with creating the idol of Murugan at Palani out of Navapashanam—a potent, medicinal amalgam of nine poisonous herbs and minerals [6]. Through alchemy, Bhogar transformed poison into a life-giving elixir, establishing Palani as a center for healing and the awakening of the Kundalini (serpent power). The idol is thus not merely stone but a concentrated form of the Siddha’s subtle energy.

The texts reveal that Bhogar’s spiritual mission extended beyond the boundaries of India. Following his consecration of the deity at Palani, Bhogar traveled to the island of Sri Lanka. He was drawn to Kataragama (then known as Katirkamam) because it was a natural vortex of Shakti (energy). Ganapathy’s work describes that Bhogar viewed Katirkamam as the "southern counterpart" to Palani. According to Siddha lore, Boghar regarded the deity at Kataragama as inseparable from the presence at Palani, emphasizing the concept of Murugan as a deity who transcends geographical boundaries.

The Legend of the Kalyangiris

Historical and spiritual analysis reveals that three distinct sages named Kalyangiri resided and attained samadhi at Kataragama, playing pivotal roles in the temple's development.

The First Kalyangiri

The first Kalyangiri was a tapasvi (ascetic) from North India, belonging to the Giri Order of the Dasa Namis. He arrived intending to take Skanda back to India, but remained after a divine intervention. He performed intense tapas for twelve years using japa yoga (recitation of the Sadakshara mantra) and prepared a Shatkona Yantra. At the end of his penance, he received a vision of Skanda and Valli in the Menik Ganga. When he attempted to ask a boon to take Skanda to India, Valli intervened (thali picchai), begging him not to separate them.

Kalyangiri granted her wish, constructed the temple for Theivani Amman and the Kalyana Mandapa, and installed the Shatkona Yantra in the sanctum sanctorum. After his liberation, his body is said to have become a Muttu-lingam. The Dakshina Kailaya Manmiam documents this first Kalyangiri [7].

The Second Kalyangiri

The second Kalyangiri is believed to have lived during the beginning of the 7th century A.D. A renowned tapasvi, he is credited with performing miracles and managing the temple's affairs.

The Third Kalyangiri and King Rajasingha I

The third Kalyangiri lived during the reign of King Rajasingha I (1581–1592 A.D.) and the early part of King Rajasingha II's reign. He was the son of Amarnath, a high-caste Brahmin and disciple of Sri Sankaracharya Swamy of Sringeri Mutt.

King Rajasingha I extended unstinting patronage to the Kataragama Temple. Tradition holds that the king suffered from Pitruhati (the ill effects of patricide) and lost his peace of mind. He met Kalyangiri at Kataragama, who was then building the present Swamy Temple, Theivanai Amman Temple, and Valli Amman Temple. Under Kalyangiri’s instruction, the king performed rituals to absolve himself of his sin and funded the temple's completion. The Mahavamsa (Chapter 93, verses 7-16) and the Kadiramalaip pallu both reference this patronage [8].

Sacred Infrastructure of the Temple Complex

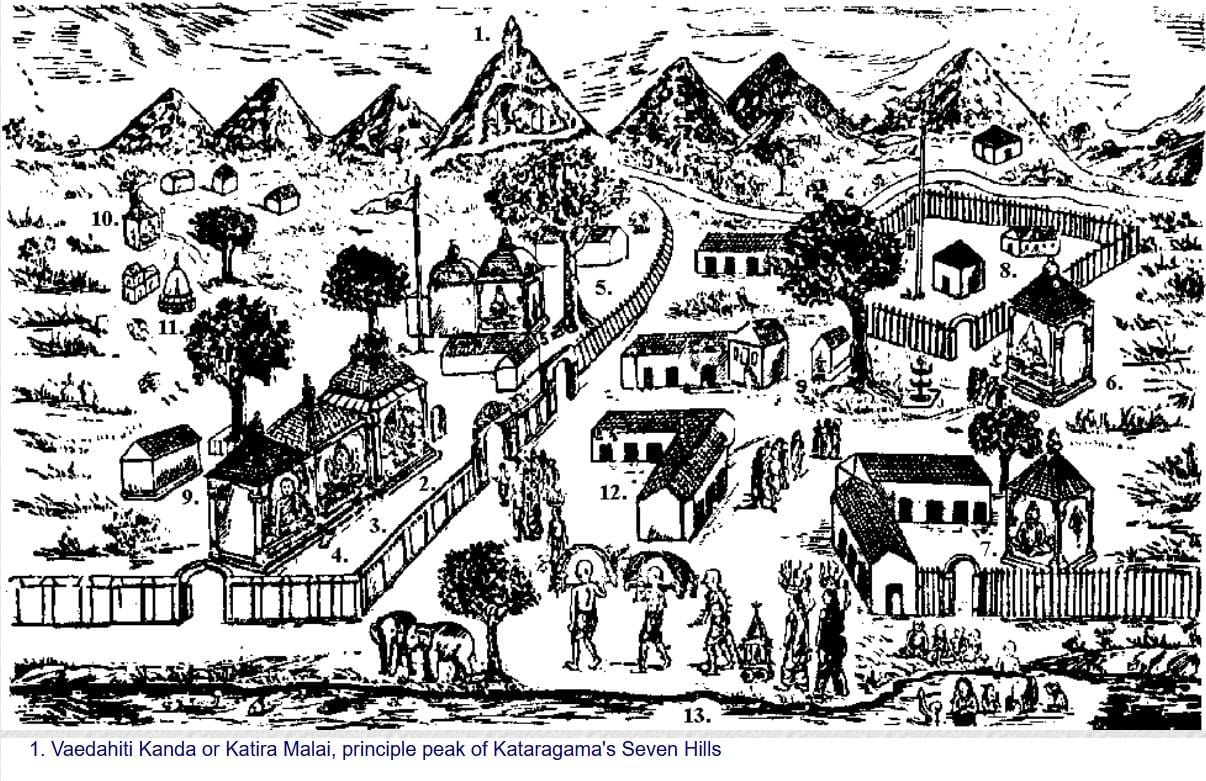

The sacred infrastructure of Kataragama is not limited to a single building but encompasses a diverse array of shrines, each with its own specific dedication and function:

The Central Complex: This area enshrines the Kandaswamy Mulastana (the principal sanctum), along with a constellation of subsidiary temples including the Sivan Kovil, Subramaniyaswamy Kovil, Vairavar Kovil, Lakshmana Perumal Kovil, Aiyanar Kovil, and Pathini Amman Kovil. It also houses the distinct shrines dedicated to the consorts, the Valli and Theivani Temples.

The Pillaiyar Shrines: The Mannikkapillaiyar (Ganesha) Kovil is a significant shrine, closely associated with the Vishnu Kovil, forming a dedicated complex for the worship of the remover of obstacles and the preserver.

The Muthulingaswamy Kovil: This shrine houses the Muttu-lingam, the pearl-like manifestation associated with the first Kalyangiri.

The Community Shrines: Extending into the local community, the Manikkapillaiyar Kovil is situated in Sellakadirgamam, integrating the sacred geography with the daily lives of the residents.

The Mountain Shrines: Finally, devotion reaches its zenith on the slopes of the mountain called Kadiramalai.

Wedihitikanda: The Mountain of the Arrow

The sacred geography of Kataragama extends beyond the main temple complex to include the rugged peaks that surround it. Approximately 3 km northwest of the main temple lies Wedihitikanda (or Vedi-hiti-kanda). This mountain peak is intimately linked to the arrival of Skanda and the establishment of his abode.

The name translates to "the hill where the arrow fell." Legend states that the God shot an arrow from the sacred mountain of Kailash in India to determine the location of his earthly abode; the arrow landed here, marking the spot where he would settle. It is also believed to be the specific location where Skanda meditated in the form of a Yogi (ascetic) before establishing the main temple, further solidifying the area's status as a center for spiritual power.

Customs and Modes of Worship

The customary mode of worship is distinct. Pilgrims take a dip in the cool waters of the Menik Ganga early in the morning and proceed to climb the Kadiramalai with their wet clothes on. They perform pradakshana (circumambulation) around the shrines upon returning from the hill. The devotion is so intense that pilgrims often utter only "Arohara" (salutations to the deity) while bathing or climbing to maintain the spiritual atmosphere.

The Spiritual Lineage of the Kataragama Matha

The spiritual lineage of the Kataragama matha continued through a succession of Giri sannyasis. Swamy Mangalpuri attained samadhi in 1873 and was succeeded by Swamy Sivarajapuri. During the time of Swamy Jayasinghegiri, a young ascetic named Keshopuri from Prayag arrived. He spent years in the forests of Samanalakanda (Sri Pada) performing tapas, living only on leaves and roots.

Swamy Surarajapuri, a former commander in the Kashmiri Maharaja’s army, was directed by a vision of Skanda at Rameshwaram to find Keshopuri. He brought him to Kataragama, where Keshopuri survived only on milk, earning the name ‘Palkudi Baba’. Palkudi Baba served as Madadipathy for 25 years. Before his samadhi in 1898, he established Trust Deed No. 2317 (dated 09.03.1898) on the advice of Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam, securing the management of the Theivanai Amman Devasthanam properties [9]. Following Palkudi Baba, Swamy Surarajpuri attained samadhi shortly after.

In 1922, Swamy Sukirtapuri became Madadipathy but attained samadhi in 1933. Swamy Ganeshpuri attained samadhi in 1939 and was succeeded by Swamy Ramgiri, who managed the affairs until 1976. Ramgiri appointed his disciple, Swamy Dattaramagiri, as the Trustee and Madathypathy via his Last Will dated 20.2.1976.

Conclusion

This article draws from a publication being released on Hindu temples of Sri Lanka, highlighting a history of worship, shrines, and royal patronage across the country. Several central questions arise: If idols and gods have their roots in India, and priests likewise, how were these ideas of Hinduism shared from India? How were the forms of the idols replicated, and who conducted the pujas? Priests have travelled great distances to come to Kataragama. How is it that non-Hindus are seen adhering to “Hindu” gods?

Is it being suggested that the Shakthi of the Creator is universal — that adherents can belong to any creed or colour, that across cycles of birth they may be physically located in different geographical lands, and that human beings, across ages and even today, seek comfort and succour in the divine?

Kataragama, or Kadirgamam, stands as a classic example of this intricate cultural and spiritual synthesis. One downside, however, is that notwithstanding this rich tapestry, our people at large have little knowledge of the totality referred to here.

References

Ellawala, H. Social History of Early Ceylon.

Skanda Upada.

Arunachalam, Sir Ponnambalam. The Worship of Muruka or Skanda.

Arunakirinatar. Tiruppukal (15th Century).

Kadiramalaip-pallu (16th Century).

Ganapathy, T.N. The Yoga of Siddha Bhogar.

Dakshina Kailaya Manmiam.

Mahavamsa, Chapter 93, verses 7-16; Kadiramalaip pallu.

Trust Deed No. 2317, dated 09.03.1898, advised by Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam.