You look better today,” I said as I absentmindedly began writing her prescription. She was one of my regular patients—a gentle old lady who had been coming to my clinic for years.

Her main complaint had always been her lack of appetite. Each time she mentioned it, I reassured her that it was likely due to her chronic lung condition. I never thought to ask beyond the surface, never questioned what lay beneath this persistent symptom.

Then, one day, she quietly revealed something that shook me.

“I haven’t had lunch in 22 years.”

I looked up in disbelief. Had I misheard? Twenty-two years without lunch? Guilt crept over me. How had I never asked her about her meals, her daily routine, or her family? I knew she had three daughters. I knew her eldest daughter had been widowed at a young age—a sorrow that weighed heavily on her. But I had never asked about her son.

Hesitantly, I asked, “Why?”

She took a deep breath, her frail hands trembling as she reached for the worn purse she always carried. Her eyes filled with tears, but she did not let them fall.

“I was waiting for my son to come back.”

The words hung heavy in the air.

Her son—her youngest, her only boy—was just nineteen when he left for a tuition class one Sunday in 2000. He never returned. A friend had seen him being taken into a military bus along with a few others.

“He will come back,” the friend had assured her.

But he never did. She refused to believe he was gone. She could not accept it. And so, she waited.

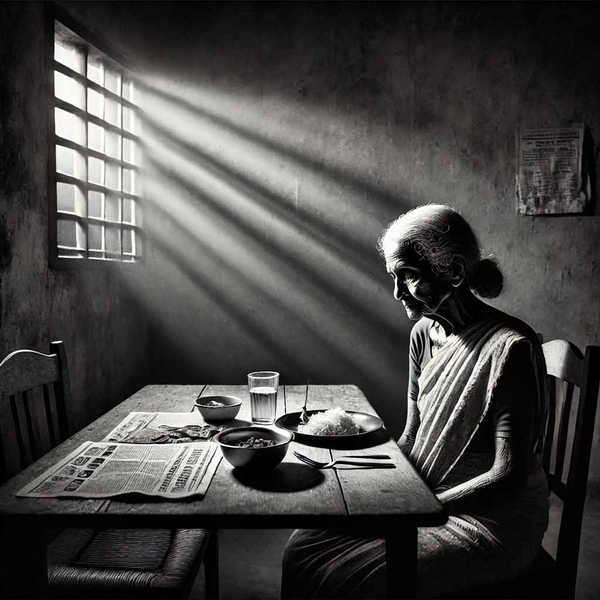

Every single day, she cooked his lunch, just as she had on that fateful Sunday. But she never ate. How could she, when the plate meant for him remained untouched?

She searched for him tirelessly. Alone, she visited every police station, every army camp, pleading for answers. She collected every newspaper that printed his name in the lists of the disappeared, clinging to each mention as proof that he was still out there somewhere, waiting to be found.

The International Red Cross sent her a pocket calendar every year—a small reminder that they had not forgotten, that they would help her, and that maybe, one day, she would find him.

She carried with her a collection of torn, faded newspaper clippings—each one a fragment of hope—tucked safely in her purse, always close to her heart.

She attended every protest and every meeting held by families of the disappeared. She traveled miles whenever there was even the faintest whisper of new information. Recently, she had been called to a distant district and was given a serial number—some kind of record, but not the answer she longed for.

She did not allow herself to grieve. To grieve would mean accepting that he was gone. And she could not do that. She believed her son was alive and that he would return.

But time was slowly betraying her. Her body was growing weaker and her weight was dropping, though her hope never wavered.

At her last clinic visit, she told me softly, “I will see my son before I die.” Then, as if sensing my silent doubt, she added, “And if I don’t, I have left a letter with the Grama Sevaka. My body must not be cremated until my son returns to do my last rites.”

I sat in silence, listening, as I always did. Her frail frame worried me. Each visit, the scale confirmed what my eyes could already see—her body was fading, even as her hope burned bright.

Each time I gently urged her to eat, she would smile faintly and say,

“Don’t worry, doctor. I will not die until I see my son.”

And I knew she was not alone. There were so many mothers like her—so many wives, sisters, and daughters who had spent decades waiting, searching, clinging to memories and to hope.

Their stories, their suffering, their quiet endurance—slowly fading from the world, just like them. But for those who still waited, hope was their lifeline. It was the only thing keeping them—and the untouched meals of their lost loved ones—alive.

And so, I prayed. Not just for her son to return, but for the flame of hope in her heart to burn strong until her last breath. Because as long as she hoped, she lived. And in her heart, the lunch she made for her son 22 years ago remained warm, untouched—waiting, just like her.