Life can be quietly ironic. Less than a month after I interviewed Professor Sir Sabaratnam Arulkumaran and titled the piece “The First Sri Lankan Tamil Knight in 50 Years,” another Sri Lankan Tamil was honoured with a knighthood. This time, it was Nishan Canagarajah, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leicester.

At the age of fifteen, while his elder brothers were studying at universities outside Jaffna, a Grade 9 Nishan spent three days and nights at Jaffna Hospital caring for his dying father, Canagarajah. A childhood friend recalls being denied entry by hospital staff, who said the scene inside was too distressing for a minor, given the severity of his father’s condition. Yet the irony was this: that same fifteen-year-old—still a schoolboy—remained steadfast at his father’s bedside throughout. After three days of intense struggle, his father passed away, a loss that would, in many ways, reshape Nishan’s life.

Even before this period, a series of difficult personal circumstances had pushed the family into financial collapse, leaving them burdened by mounting debts. Friends recall how creditors came to the family home and demanded repayment in the harshest possible ways. A much younger Nishan witnessed these scenes in silence, absorbing the distress they brought into the household.

Through those years, however, those who knew him remember a young man of quiet dignity. A close friend recalls that he faced mounting challenges with a steady smile. “You cannot imagine him without smiling,” the friend said. “No matter the hardship, that smile never left him.”

Another friend recalls that even amid these hardships, Nishan maintained his daily routines with discipline—studying, running, and training for sports with quiet regularity—as if he were determined to turn every challenge and humiliation into fuel for his life’s trajectory.

Even after earning his degree from Christ’s College, Cambridge—the first in his school batch to graduate from any university, at a time when many others in Sri Lanka had their studies disrupted by the second JVP insurrection—Nishan returned home. His childhood friend Victor Thevakumar recalls that he and a few others went to the airport to receive him. Among themselves, some wondered whether he might have changed after studying at a prestigious institution like Cambridge—whether he would now speak only English, have forgotten Tamil altogether, or arrive dressed in a suit. Victor reassured them otherwise. “You will see him,” he said. “He will come wearing the same brown trousers he wore in Jaffna, and simple Bata slippers.” Victor was right.

That constancy remained unchanged years later. When Nishan’s St. John’s batchmates learnt that he would be passing through Toronto for just a few hours in July 2023, they organised a surprise reunion lunch. To make it special—and deliberately nostalgic—they arranged a traditional meal served on banana leaves. Some wondered whether Nishan was still the same person they had known decades earlier, now that he was a Vice-Chancellor. But a few friends who knew him well reassured the group that he would be. They were right.

A long-time acquaintance notes that Nishan speaks even to children with respect, using plural forms of address such as “neengal” and “naangal”—honorific Tamil pronouns traditionally reserved for elders or equals, and rarely used when addressing someone younger. The gesture reflects his instinctive courtesy. The same friend adds that you will never see him speaking to someone while remaining seated in his chair; he always stands up to greet people, regardless of who they are.

Another friend puts it more simply: when fellow schoolmates or people from Jaffna ask which A-Level batch they belong to, they do not say “the 1985 batch.” Instead, they say, “We are from Nishan’s batch.”

That boy who stood vigil in Jaffna Hospital, who sometimes went to school without food and borrowed boots to play football, is today the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leicester—recently knighted for services to higher education and equality. His career has been devoted to creating opportunities for others: supporting refugees, building research capacity in Sri Lanka, and championing diversity within British academia.

More than the titles, his life offers a quieter lesson—that no matter how high one rises, the greatest achievement is to remain humble and connected to one’s roots.

In his first interview since being knighted, Sir Nishan Canagarajah reflects on poverty and opportunity, the moral dilemmas of choosing education over militancy during wartime, migration and identity, and what it means to lead institutions with both excellence and grace.

Sir, congratulations on your knighthood. At a time when hostility toward migrants is growing in many parts of the West, you have received one of the highest national recognitions. As someone who began his journey as a migrant, how do you reflect on this moment?

I think there are three points I would make.

First, there is ample evidence that migrants make valuable contributions to the countries in which they live. If you look at academia, healthcare, or business, there are many examples across the West where migrants have made significant and positive contributions. When those contributions are truly extraordinary, it is encouraging to see countries recognise them. In that sense, it is heartening that a country like the UK values migrants’ contributions and honours them accordingly. This is a positive development not only for migrants but also for the West itself, as it reflects an ability to acknowledge merit and contribution through such awards.

Second, talent exists everywhere. People around the world possess immense potential, and there are many ways they can contribute to society.

Third, the real problem we face globally is not a lack of talent, but a lack of opportunity. This recognition demonstrates that it does not matter whether you are a migrant or a native—if you are given the opportunity, you can achieve remarkable things.

That, I believe, is an important point to recognise: there are talented individuals all over the world, and when the West provides them with opportunities, everyone benefits.

How do you view this success personally, sir?

It was quite humbling. I think it is lovely to have this endorsement. When you do things in your career, you don’t always think, I’m going to get this award one day. You simply do what you do because you enjoy it, because you think it’s the right thing to do, because you want to make a difference. You do these things, and when something like this happens, you are happy.

But it is also nice when other people say, " No, what you have achieved is something special, and that they can honour it with this award. So that, in itself, is a nice thing.

The second thing I would say is that this honour also reflects so many others who have been part of this success, because nobody can achieve all this on their own. Clearly, I have played my part, but I could not have done everything on my own. There are people who, at various stages of my life, have offered advice, created opportunities for me, encouraged me to do things I didn’t think were possible, or supported me when I was struggling.

So recognitions of this kind are not simply individual successes; they are shared successes. For me, one of the key points I want to make is that, as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leicester, where I have made a number of changes, this award also reflects the progress the University of Leicester has made and the good work it is doing. So it is not simply an award for me; it is also a recognition that the University of Leicester is doing great things. It cannot be just about me.

Sir, is there any religious, philosophical, or ethical framework that guides your life and work?

I used to be a very strong Christian when I was in Sri Lanka. I think it is true to say that some of my outlook is shaped by the idea of service—of doing good for others. That element is certainly there, but I don’t think it is specific to any one religion.

If you read across religions, they all share this philosophy: doing good, helping the poor, and supporting the vulnerable. That is a common theme in every faith.

For me, that has been the guiding factor, partly because I grew up in financially challenging circumstances and amid many difficulties. I feel that I reached this place because someone gave me an opportunity. As a result, I feel a responsibility to do something similar—to create opportunities for others. That has been my guiding principle throughout.

Sir, you mentioned that you grew up amid financial difficulties. Could you tell us a little more about that period of your life?

Growing up in Jaffna, we did not have much money. We never owned a house of our own and lived in rented accommodation throughout my childhood, which meant moving every couple of years. Both my parents were teachers, yet our financial security was very limited, and certain personal choices within the family further deepened our difficulties.

We had no savings, so life was often hard. Schooling brought some opportunities, but there were also moments of real struggle. Even something as simple as playing football could become a challenge—I did not always have the money to buy boots and often had to borrow them from other players. There were times when we went to school without food, simply because finances were stretched.

I was fortunate to receive a scholarship from my school, which meant my parents did not have to pay school fees. That made a significant difference. Still, overall, it was not an easy period financially.

There were also family responsibilities and pressures that we were not fully aware of at the time, which only became clear later. When my father passed away, we discovered that a number of financial obligations had accumulated over the years. My elder brother, who was then at university, worked as an English instructor and gradually helped to clear those commitments.

Eventually, all four of us received scholarships to study in the West. Without those opportunities, we would never have achieved what we have. The period between the ages of 12 and 15 was especially difficult. My father died when I was 15. I spent three nights with him at Jaffna Hospital; he passed away on the third night.

Looking back now, do you feel that the poverty you experienced as a teenager shaped who you are today?

Absolutely—absolutely. When you are given an opportunity after going through tough times, you realise that any help you receive matters deeply. You want to make the most of it, and you also want to be grateful to the people who helped lift you from that position.

Even now, in Leicester, I actively support refugees. I’ll give you one example. When Afghan refugees began arriving in the UK, we launched a programme to support them. Some of the women had never learned to read or write, or had never been able to speak publicly. We created a programme to help them develop basic literacy and communication skills, and that initiative has now grown into a national programme in the UK.

Similarly, I have been involved in supporting Palestinian and Ukrainian refugees. This work is partly shaped by what I personally went through, and by what I witnessed in Jaffna—how refugees were treated and supported there. Even when I was living in Jaffna, I was quite involved with the church. In Ariyalai, there was a refugee camp, and on Saturdays, I would go with a small group to provide extra support.

I was doing this even at the age of 14 or 15, visiting refugee camps and helping in whatever small ways I could. That experience has stayed with me. I always try to do what I can, wherever I am. I wish I could do more, but whenever possible, I want to use the opportunities I’ve been given to support others as well.

You grew up in Jaffna during intense conflict—from the burning of the Jaffna Public Library to the violence of 1983, when fear, anger, and political radicalisation shaped many young lives. Some of your classmates and seniors later chose militant paths, while others took very different directions.

Looking back, how did those experiences shape you personally, and why did you come to believe that education—rather than violence—was the right path for you?

That’s a really good question, and it’s something I struggled with at that age as well. As I mentioned earlier, I had a strong Christian faith at the time, and that certainly played a part in how I viewed things.

I knew Raheem—who later became a spokesperson to Kittu, the LTTE’s Jaffna commander—very well; we were at school together, as you know. This was the kind of environment I was exposed to. Another close friend of mine, Mahendraraja, left school when he was about 18. One day, we went to school and were told he was no longer there—he had joined the movement. Sadly, he later lost his life.

Many of my friends joined the armed groups, and tragically, many of them lost their lives. So it was extremely difficult. On the one hand, you saw friends and people around you taking up arms, and I often asked myself whether I was being selfish by not doing the same, by not doing what I thought might be expected of me for the community.

At the same time, I felt that perhaps I could contribute more through education, through the skills I had and the things I might be able to achieve that way. Given the economic conditions my family was facing, education also felt like the most realistic path for me.

It was not an easy choice. Even now, I don’t know if there is a clear or “right” answer. I have a great deal of respect for many of my friends who chose to take up arms, believing they were fighting for freedom and for their community. Growing up in that period involved a constant moral dilemma: Are you making the right choice?

Could you tell us how St. John’s College contributed to shaping who you are today?

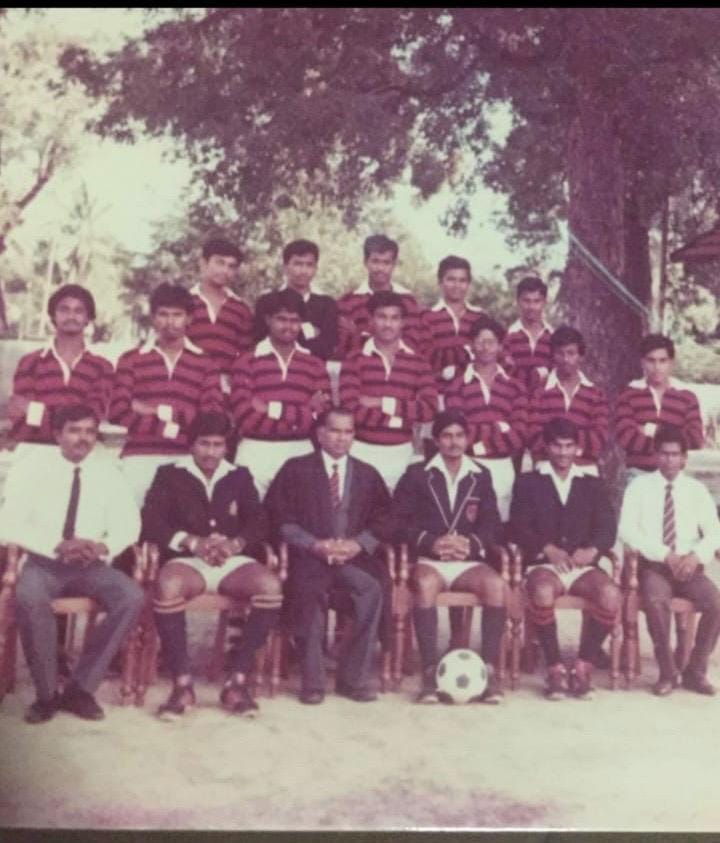

Yes, I think what was special about St. John’s was that while there was strong academic support and an emphasis on doing well academically, education there was not limited to academics alone. There were many opportunities to express and develop one’s talents. In my case, I was deeply involved in sports, I was interested in drama, and I also took part in committees such as Interact, which focused on organisation, working with the local community, and carrying out social projects.

What St. John’s offered was a well-rounded education—one that allowed you to develop a range of skills beyond the classroom. Even today, when people ask me about leadership and how I reached this position, I emphasise that certain skills are essential at any stage of life, regardless of the field you are in.

Skills such as communication, sharing ideas clearly, and persuading others to work toward a common goal are crucial. Those skills were developed at St. John’s through the leadership roles I took on. I was involved in Interact Club activities, served as its president, and later became Senior Prefect. In these roles, I had to set clear goals, communicate them effectively, and bring people together—because ultimately, leadership is a team effort.

These are skills you don’t acquire simply by studying textbooks. You develop them by doing—by learning how to work with people, how to achieve results, and how to decide what truly matters. Even now, as Vice-Chancellor, those same principles guide me: setting a clear strategy and vision, ensuring the team understands it, and working together to deliver results.

You were a remarkable sportsman during your school days, excelling in several sports. How did your involvement in sport shape your sense of discipline? And how did it influence your understanding of teamwork and your approach to leadership later in life?

My Wikipedia page says I excelled in sports like cricket, football, volleyball, and hockey—but that’s not entirely accurate. Not cricket, and not volleyball. I actually played football, hockey, basketball, and athletics.

Sport played a very important role in my life. In fact, I always encourage people, if they can, to take part in team activities, because they teach you how to motivate others and work together—especially when things get difficult. When a team is not performing well, the real challenge is how you motivate people to give their best.

Those are exactly the same skills you need when you are leading a large organisation. Sport instilled discipline in me and shaped my approach to leadership in very real ways, and I benefited enormously from that experience.

I also genuinely enjoyed it—I loved playing sport, I loved competing, and of course, I loved winning. But one of the most important lessons sport teaches you is how to accept defeat. Life is not about winning all the time. There are moments when you lose, and then you have to pick yourself up and try again.

These are lessons you learn on the sports field, not from reading a textbook.

Do you still actively take part in sports?

Yes, I do—but not team sports anymore, mainly due to time constraints, so I’ve had to stop those. These days, I focus on running and going to the gym to keep myself fit. In fact, I’ve just come back from the gym.

I go regularly to stay active and healthy, and I genuinely enjoy it. Maintaining physical fitness remains an important part of my routine.

You have said in an earlier interview that winning a scholarship after your A-Levels and coming to England was the single event that changed your life. Could you tell us how you secured that scholarship, and how that opportunity transformed your academic journey and your sense of what was possible for you?

Yes, massively. That really was a key turning point. Otherwise, I had the grades and had already secured admission to the University of Peradeniya to study engineering.

Then one day, my school principal told me that there had been a request to nominate candidates for a scholarship to study at Cambridge and asked me to apply. He was very clear with me: don’t build up your hopes—it’s extremely competitive. I was one of four students nominated from St. John’s, and there were nominees from other parts of the Northern community as well.

I was subsequently invited for an interview. A panel of senior professors from Colombo came down to interview about four candidates. Following this, I received a letter offering me a scholarship to study at Christ’s College, Cambridge, and I was absolutely delighted. I should add that I was not the first recipient; this was part of a scheme established to support students from the Northern region in the aftermath of the 1983 riots.

One person had received the scholarship before me, and after me, about five others from Jaffna and the wider Northern Province were selected under the same scheme.

Looking back, do you see your success as the product of talent alone, or also of access and opportunity?

You need opportunities in life. You may have talent, but talent without opportunity amounts to very little. Opportunities matter just as much. That is something I firmly believe in.

That belief has also guided much of what I have done—creating opportunities for others. There are many people with talent who never get the chance to realise it, and, as I see it, my responsibility is to help create opportunities for them to succeed.

So your success is a combination of talent and access?

Absolutely—absolutely.

Sir, in a previous interview, you mentioned that you always wanted to become a professor. How did that aspiration first emerge?

It’s a good question, and it’s not an easy one to answer. I think one important factor was that both my parents were teachers, so that may well have played a role.

I was drawn to the university environment because it seemed like a good place to work, engaging with people at a later and more reflective stage of their lives. I also genuinely enjoyed doing research. If you want to combine research with teaching, then working at a university is the ideal path.

I never set out with the ambition of becoming a vice-chancellor. My aim was simply to be a good lecturer—to do meaningful research and to teach well. If that is your goal, then the natural academic aspiration is to become a professor one day.

That was what I was working toward, and everything else followed from there. I never planned my career around becoming a vice-chancellor; that came much later.

A perception has emerged in some sections of the Tamil community that your success was possible largely because you left Sri Lanka, and that it was tied to distancing yourself from the country. How do you respond to this view? And do you believe you could have achieved a similar level of professional success had you remained in Sri Lanka?

I think it is difficult to give a definitive answer. I also have to be careful, because I left Sri Lanka nearly forty years ago, so I cannot claim first-hand knowledge of how things are today.

That said, it is partly true that many of the things I have achieved were possible because I left Sri Lanka—there is no doubt about that. For example, I would not have been able to carry out the kind of research I have done had I remained in Sri Lanka, simply because the necessary research infrastructure and expertise were not available at the time. I would not have been able to build my standing as a researcher in the same way.

Similarly, many of the international opportunities I later developed for universities in the UK would have been very difficult to pursue within the constraints of the Sri Lankan system. In that sense, several aspects of my professional journey would not have been possible had I stayed. The system was simply not structured to support that kind of work.

However, I would strongly reject the idea that I have disowned Sri Lanka. Even now, wherever possible, I try to contribute in meaningful ways. I have supported research initiatives at the University of Jaffna, and during my time at Bristol, I helped create opportunities for Sri Lankan students to pursue PhD studies in the UK. These may not be large-scale interventions, and I don’t want to overstate them, but they matter to me.

Ultimately, while it may be fair to say that much of my professional success after my education in Sri Lanka unfolded outside the country, this does not mean that I have severed my connection to Sri Lanka or ceased to feel a sense of responsibility toward it.

How do you define yourself today—Sri Lankan, Sri Lankan Tamil, migrant, British, or beyond such labels?

I think it’s very hard to pigeonhole me into a single label, and I do struggle with that. I don’t think I can define myself in just one way. I see myself as Sri Lankan, and I also see myself as British Asian.

Those are the two labels I would probably use to describe myself today.

Do you feel emotionally distanced from Sri Lanka and Sri Lankan society after living abroad for so many years?

No, not at all. When the announcement was made on the 31st, I had a small celebration here, and about forty people attended. They were all Sri Lankans, including friends who went to School with me in Jaffna. Those are the people I chose to celebrate this award with.

You are widely recognised for bridging deep technical scholarship with institutional leadership. How challenging was the transition from being a researcher to becoming an administrator and leader? Do you see these roles as interconnected, or do they require two very different mindsets?

They require different skill sets. In terms of academic expertise, you need to be strong in research, good at problem-solving, and effective in teaching. Those are the core skills required to be a successful academic.

However, when you move into leadership—whether as a manager or an administrator—you need a broader range of abilities. Leadership is about understanding how an organisation works as a whole. As an academic, your focus is often quite narrow: your research, your teaching, and your specific field of expertise.

By contrast, when you are running an organisation, you have to recognise that there are many different people involved, each with their own priorities and ambitions. The institution also has external expectations and constraints. Leadership, therefore, is about balancing all of these factors in a thoughtful and effective way.

That transition is not easy. The key skill you develop in moving from academia to leadership is the ability to understand the system as a whole—and then to design a clear vision, strategy, and plan to move the organisation forward. So the two roles are not mutually exclusive, but they do require distinctly different skill sets.

You are one of the very few Sri Lankan Tamil leaders who has exercised influence through ideas, institutions, and personal credibility rather than through force. In societies like ours, power has often been shaped by arms and coercion. Your journey represents a very different model. How do you reflect on that form of influence?

I think all of these approaches have their place. Throughout history, there have been many examples where the power of persuasion has prevailed over the use of force. At the same time, there are cases where persuasion failed, and force was seen as the only way to achieve a particular outcome. So there has always been a role for both.

In my own case, yes, you are absolutely right—the power of persuasion and ideas helped me overcome the challenges I faced, and it worked. But I also recognise that this approach does not work in every context. The key is understanding where it is effective and pursuing it in those situations.

I believe persuasion is an effective way to move an organisation forward. While force may succeed in certain circumstances, its sustainability in the long term is a different question altogether.

In an era when universities are under pressure to be both market-oriented and socially conscious, what do you believe a modern public university should stand for?

Ideally, a university should strive to do both. However, the reality is that resources are finite. If a university had unlimited resources, it could fully embody social responsibility, ethical leadership, and everything we expect from a good public institution. But when resources are constrained, difficult choices have to be made.

In those circumstances, prioritisation becomes essential. You have to focus on activities that align closely with the university’s core mission and values. That is how I approach leadership—by ensuring that decisions are driven by values and informed by local priorities. Inevitably, that also means having the discipline to say no to certain things.

You have reached the top of British academia at a moment when artificial intelligence (AI) is beginning to fundamentally disrupt the traditional higher education model. Many see AI as both an opportunity and a threat. How do you view this transformation? Do you see AI primarily as a positive force or as a disruptive challenge for universities and students?

I think AI is broadly positive. It has many beneficial attributes—it helps us do things better, faster, and more efficiently. That said, I think some of the claims being made about AI are premature. It is still too early to say exactly how it will transform society, so we need to approach it with a degree of caution and allow time to see how it develops.

Similar arguments were made when the internet first emerged—that it would take over everything, that we would no longer need libraries or books because everything would be available online. Likewise, during the Industrial Revolution, there were fears that automation would eliminate the need for human workers altogether.

What history has shown us is that while technology does change how we work, it does not fundamentally remove human involvement from society. Instead, it reshapes the kinds of work people do. I believe the same will be true of AI.

The challenge, therefore, is not to resist AI, but to learn how to coexist with it—how to integrate it in ways that complement human capabilities rather than replace them.

In the context of education, AI clearly has an important role to play. It allows rapid access to information and can support learning in many ways. However, universities are also places where students develop other essential skills—critical thinking, communication, teamwork, and judgment. These are not skills that AI can easily teach or replace.

Human judgment, in particular, remains irreplaceable.

Do you believe universities should remain politically neutral spaces, or do they have a responsibility to take principled positions on issues of injustice and war?

It is very important that universities remain neutral so that they can accommodate and encourage different viewpoints. Otherwise, they risk becoming institutions that do not genuinely support academic freedom and freedom of speech. I believe safeguarding those principles is far more important than taking an institutional position on a particular issue that aligns with a single viewpoint.

You lead a student community of nearly 20,000 students. According to your university’s data, around 46 per cent of them come from UK ethnic minority backgrounds.

Returning to the question I raised earlier, at a time when migration has become a politically contested issue, how does this level of diversity shape inclusion within the university?

It is challenging—yes, it is. But I am very proud that we have one of the most diverse student communities. I am proud because these are all talented and capable students who meet the standards required to study at a good university, and they deserve the opportunity.

Another reason I am proud is that a university environment allows students to develop not just academically, but also as individuals. When you engage with people from different backgrounds—different nationalities, cultures, and ethnicities—your perspectives are shaped by those interactions. In my view, that makes you a better graduate and a better person when you leave university.

For me, that is incredibly important. Yet there are those who believe—wrongly, in my opinion—that diversity somehow dilutes academic standards or excellence. I do not believe that is true. You can have excellence and diversity at the same time.

In what ways are you currently giving back to Jaffna society?

At the moment, I work closely with the University of Jaffna Medical Faculty. I have been involved with them for more than 5 years, helping to develop research capacity—particularly in conducting research and engaging with overseas universities.

I have worked closely with the JMOA, the Jaffna Medical Officers’ Association, through which I was introduced to several academics and collaborators. As a result of that engagement, we established a Centre for Digital Epidemiology at the University of Jaffna, which I had the privilege of opening in 2023 during my visit to Jaffna.

That centre is now working very closely with universities such as Birmingham, Leicester, and Bristol—institutions with which I have professional connections. Wherever possible, I try to contribute by helping universities in Sri Lanka develop their research capacity and strengthen their ability to engage internationally.

I strongly believe that Sri Lanka needs to invest more seriously in university-based research. At present, research activity remains limited, and if we are to address the country’s challenges—and also create better opportunities for academics—we need to strengthen research culture within our universities. I am very happy to play my part in supporting that effort.

Sri Lanka has long relied on a strong state-run university system, and historically, there has been significant opposition to private higher-education institutions—especially private medical colleges. In your view, are private medical institutes necessary for Sri Lanka? And if so, under what conditions should they operate within the country’s higher-education framework?

Again, it depends on how the country understands and plans for its future needs. I don’t have all the data, but the principle is quite clear.

Let me give an example. If a country determines that, over the next ten years, it will need X doctors, Y nurses, and Z radiographers to meet the needs of its population, then the next question is: how many of these professionals are our universities currently producing?

If there is a shortfall, there are essentially two options. One is for the government to expand capacity within the state university system. Given that university education in Sri Lanka is free, this would mean the government investing significantly more public funds to train more doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals.

If the government concludes that it does not have the resources to do this, it must allow other providers to step in so that the country as a whole can meet its future healthcare needs. If this dynamic is not properly understood, Sri Lanka risks facing serious problems in the long run—quite simply, if we do not train enough doctors and healthcare professionals, we will not be able to meet the needs of our citizens.

So the key question is this: if the government believes that the country already has enough doctors and nurses, then there is no need for additional institutions. But if more are needed, and the state system cannot produce them, then other providers must be allowed to do so.

Interestingly, this is the same debate that took place in India. For many years, there was strong opposition to private universities there as well. But that position changed when the government recognised that the state alone could not meet the country’s growing demand for higher education. This is also the model followed in much of the West. The state simply cannot do everything. At some point, it has to acknowledge its limits.

There is also another practical consideration. If Sri Lanka decides not to allow private medical colleges, students who fail to secure places in state universities will inevitably go abroad—to India, Bangladesh, Dubai, or elsewhere—if they can afford it. If that is the case, why not allow them the opportunity to study medicine in Sri Lanka itself, under a properly regulated system?

Jaffna lost multiple generations to war and migration. When you think of your own schoolmates who took very different paths in life, what emotions dominate you today—is it grief, guilt, gratitude, or something more complex than any single feeling?

It’s a combination of all of them.

I feel this way because, clearly, many of them sacrificed their lives believing they were acting in support of the community. At the same time, I am conscious that some of the things I have been able to do may not have been possible without what they went through and what they did.

So it is very difficult to define it as just one emotion. It isn’t a single feeling—it’s a complex mix of emotions.

If you had to distill your life’s lessons into one simple truth for a young person—especially a student in Jaffna studying for O-Levels or A-Levels—what would that be?

As someone who grew up in poverty and a conflict-affected region and went on to achieve so much, what is the most important lesson you would want young readers of Jaffna Monitor to take away from your journey?

If I had to distill my life’s lessons into one simple truth, it would be this: grasp every opportunity, because you never know where it might take you. I’m not even sure it counts as a “simple” truth, but it is the one thing I firmly believe in.

We often think we should do something only if it leads to a clearly defined reward, or because we can already see the outcome. Sometimes that approach makes sense—but not always. There are moments in life when it is important simply to say, this looks interesting, and to try it, even if the path ahead is uncertain.

For a young person in Jaffna—especially someone growing up amid hardship or self-doubt—my advice would be: don’t be afraid. You never know what you can achieve. I tried to grasp every opportunity that came my way and was willing to take risks because sometimes you have to.

There isn’t a single magic formula for success; if there were, everyone would follow it. Life is a combination of many things. But if I had to highlight one core idea, it would be this: take opportunities and don’t be frightened. Even if something feels intimidating, try it. You may surprise yourself.