Translated from the original Tamil short story yāḻppānaccāmi (யாழ்ப்பாணச் சாமி) by Shobasakthi. The original story is available at his website. If you have any questions or feedback, please contact ez.iniyavan@gmail.com.

This story is not about the Aruḷampalam Swami who was immortalized in song by the great Tamil poet Bharathiyār, calling him the eye of the world and the enlightened vessel that delivers sinners from their suffering. I am about to tell you the story of a different Jaffna Swami. The Aruḷampalam Swami that Bharathiyār met in Puduchcheri had taken a vow of silence. This Jaffna Swami was the polar opposite.

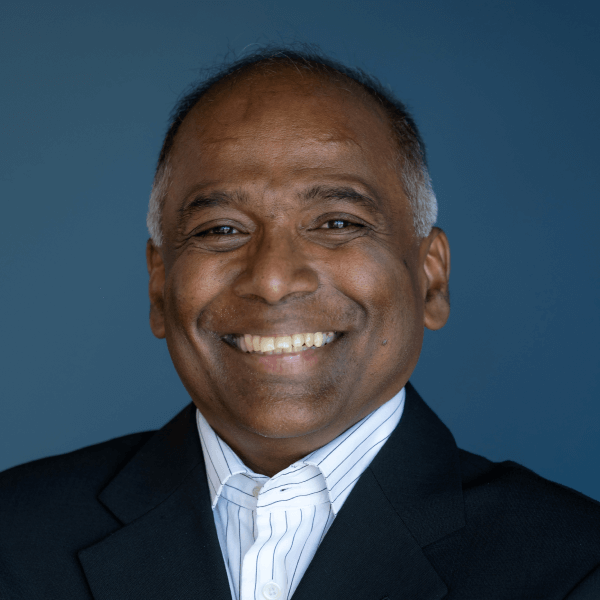

The fact that I am still unmarried is a deep source of worry for my mother. A parent’s heart is forever fraught with concern for their offspring. Ammā had sought an audience with Jaffna Swami to ask about my future. This Swami’s monastery is reportedly the place in Jaffna today with the largest congregation. He wears only a skimpy loincloth and does not accept any offering other than cooked food or peeled fruit.

My ammā had explained everything about me to the Swami and pleaded with him to give me a remedy saying, “He lives in France, and has not married yet, even though he is getting on in age.” Jaffna Swami had asked, “What is your son’s profession?” Ammā had responded with a hint of pride, “He is a big writer, Swami. His books have been published in English.” That was it. The Swami started yelling with great agitation.

“You whore, you have ruined your family… you cheap slut, you bloody rag, don’t you know how to raise a child, tell that prick to stop fucking around with writing, literature, and whatnot, and ask him to go find a real job! Only then will he find a cultured whore or a loving harlot.”

A year ago, the city of London was at its wit’s end because of this Jaffna Swami. The attention of universities, researchers, writers, champions of the Tamil race, the Scotland Yard, and the Sri Lankan High Commission were all focused on him.

The root cause of this problem was surely the book ‘Bad Word God,’ written by an Irish woman called Barbara Brickman. It was a little book telling the story of Jaffna Swami. Fifty-year old Barbara was attracted to Jaffna Swami when she worked in Sri Lanka for a few years during the war as a humanitarian worker. She called herself the ‘divine lover’ of Jaffna Swami.

The other person who was caught up in this saga was a teacher, Sathāsivam. He runs a small organization in London called the ‘Jaffna Swami sath sangam’ which he founded. Without holding anything back, I will place before you the raw story about Jaffna Swami that I learned from Teacher Sathāsivam.

2

Jaffna Swami’s birth name was Nāgēsvaraṉ. He was born in 1960 in Kāraitīvu, known as the Chidambaram of Eeḻam. He was a very active child. When the navy occupied the land on which their house stood, his family was displaced to Jaffna town. It was there that Nāgēsvaraṉ fell in with a Tamil militant group. On Deepavali day in 1983, he went to India to receive military training.

But neither the military training nor life in the militant movement turned out the way Nāgēsvaraṉ had expected. The leaders of the militant group were outright dictators. There were no democratic practices in the training camps. Nāgēsvaraṉ could not bear all this. He dared to express his protest mildly, saying “The practices in the camp are not correct, change is needed.” They arrested him and sent him to the group’s secret torture camp. He was accused of being a spy from an enemy group, and of agitating to topple his own group’s leadership.

Jaffna Swami said that this brutal torture camp was in the Nāmakkal region of Tamil Nadu in India. Prisoners who were brought to that camp were tortured, interrogated, murdered, and buried in the orchard. Nāgēsvaraṉ awaited the day when he too would be murdered.

The leader of that militant group was fond of speaking in pure Tamil. Therefore, all top-level members of the group were also learning to speak in pure Tamil. Most people in the torture camp also spoke in pure Tamil. They even gave pure Tamil names to the instruments of torture. A crowbar was called neṭṭirumpu instead of the more common word alavānku. Welding was referred to as oṭṭirumpu.

They interrogated Nāgēsvaraṉ in pure Tamil, too. He struggled to answer many of their questions only because they were in pure Tamil. He could not understand half the words in the questions. They tortured him by using words like kumukāyam, uḻaṉṟi, aṭṭil, and tumukki, none of which he understood.

He was held in solitary confinement in a hut. The guard assigned to him was barely sixteen years old. He was the only one in the entire camp who did not speak in pure Tamil. He must have taken pity on Nāgēsvaraṉ for some reason. Once, in the middle of the night, he took a spade handle, beat Nāgēsvaraṉ with it and interrogated him again. Now that Nāgēsvaraṉ could understand the boy’s questions very clearly, he cooperated with the interrogation by answering the questions properly. The boy must have realized that Nāgēsvaraṉ was not guilty. He untied Nāgēsvaraṉ’s hands and legs and said, “Hey, son of a cunt, don’t you dare think that you can fuck with the movement. Go, get lost.” Nāgēsvaraṉ only had a torn sarong on him. He kept running where his feet took him, eventually reaching the highway. He managed to beg for a ride in a truck. The truck was carrying goods for Thiruvaṇṇāmalai Aruṇāsalēsvarar temple.

Thiruvaṇṇāmalai was a town of wandering mendicants. He blended among them as a mendicant of mendicants. He was walking backwards along kirivalam, the ritual circumambulation route around the mountain, from nirutilingam to indralingam, when he realized that the obscenities uttered by the boy who released him were the sacred words that saved his life. He believed that the boy was the manifestation of the divine. He understood that all the obscenities are the words that open one’s mind to birth, love, joy, and compassion. There is no sound that is more natural or more truthful than the expletives that spring forth from the depths of one’s heart. All other words are deceptive, impermanent, and prone to change. Once he realized this truth, he began to speak exclusively in expletives.

Like other mendicants, Nāgēsvaraṉ begged for food, slept wherever he could, and spent the rest of his waking hours debating with other mendicants. The other mendicants, regardless of whatever life experience they may have had, did not have Nāgēsvaraṉ’s experience in visiting death’s doorstep and returning back to this world. He was also the only one among the ascetics there who knew how to shoot a gun, and the only one who had been an eyewitness to countless murders. Therefore, his words and arguments were rich with his lived experience. His obscenity-ridden discourse had a certain truth to it.

When the Fan Swami heard about Nāgēsvaraṉ, he sent a disciple to fetch him for an audience. On hearing this, Nāgēsvaraṉ let out a bunch of expletives and sent the disciple back with the cryptic words “more wakeful than the wakeful, soiled flower offering.” (sākkirattil sākkiram eccil pū kāṇikkai.) Eventually Fan Swami himself came to see Nāgēsvaraṉ. He was the one who first christened Nāgēsvaraṉ ‘Jaffna Swami.’

When the Indian Peace Keeping Force landed in Sri Lanka, Jaffna Swami, too, suddenly appeared in Sri Lanka. No one knew if he came by sea or air. He wore only a dirty loincloth. There were no other religious symbols on his person. His gaunt black body, and the sunken chest were overgrown with hair. His eyes were always drowsy. He walked all over Sri Lanka, eventually arriving in Mutṟaveḷi in Jaffna and taking up residence at the Muṉiyappar temple hall. All day, he would walk briskly along Jaffna’s thoroughfares. No one knew who he was or whence he came.

But would a mother not recognize her own son! Nāgēsvaraṉ’s mother who came to get an audience with Jaffna Swami, immediately recognized him. The swami blessed her by putting his hand on her head, saying “You prostitute! The matter is finished!” and sent her on her way.

This was the time when the people of Jaffna faced enormous challenges. They worried about the Sri Lankan army, the Indian army, the Tamil militant groups, fighter jets, rockets, and so on. There was no one to speak on their behalf. They had nothing to hold on to. They viewed Jaffna Swami, who came out of nowhere, as a veritable god. They were not ready to find fault or a shortcoming in the voice of god.

Jaffna Swami was the only one who had the ability to speak his mind without fear. Without any discrimination whatsoever between the military and the militant groups, he cursed everyone equally, showering obscenities, blessed them and dispensed words of wisdom. Not a single day went by without him urging them, “Avoid war, you sons of cunts.”

But rationalists were everywhere, including in militant groups and the army. They caused enormous grief for Jaffna Swami. If someone apprehended him one day, he appeared in a different place the next day. People began to say that the Swami had the ability to break out of any prison. When a rocket landed on Muṉiyappar temple, the part where he was sleeping was completely destroyed. But the next day, the Swami appeared on the Mullaitīvu beach. Barbara Brickman wrote that there was definitive evidence indicating that the Swami had appeared in multiple places simultaneously.

Barbara first met the Swami at Elephant Pass. By then she had learned to speak a little Tamil. She had had a long-standing interest in the mystic traditions of the east. She fell for Jaffna Swami in their very first meeting. She wrote that she had sex with him once in an Elephant Pass saltern; when she looked up, she saw fighter jets circling, and when she looked down, she saw that the salt had turned into charcoal.

Jaffna Swami proved that in front of an ascetic, even a King is just an inconsequential twig. He asserted that religions were misbegotten philosophies resulting from forbidden fornication. He held that the only way to approach the divine is not through rituals but through speaking truth. He explained that ‘gu’ meant ‘soul,’ and ‘ru’ meant ‘destruction.’ and therefore a guru is one who destroys the soul. He declared that the governance of a country should be in the hands of its women. One day, Swami disappeared from Jaffna. The people of Jaffna awaited his return, hoping that just as before, he would suddenly appear.

3

‘Bad Word God,’ the book that Barbara Brickman wrote about Jaffna Swami, was published by a run-off-the-mill publisher in London. But somehow the book found its way to the film director Benni Zenabu. When Benni Zenabu read that small book, printed with photographs of Jaffna Swami, he cried out in exhilaration, “Here is another Zarathushtra.”

Benni Zenabu was forty years old. He is from Somalia. When he escaped the civil war, stowed away in a cargo ship, withstanding hunger and starvation, and reached England’s Portland harbor, he was just nineteen. He worked in gas stations at night and studied during the day. He joined the national film institute in England to train as a film director. When Benni Zenabu graduated, he was thirty-one.

He worked for four years as an assistant director and a co-director with several senior movie directors. At thirty-six, he completed his first screenplay. It was a story about the Somali pirates, called ‘Sweet Pirates.’

Armed with the screenplay, Benni visited every single production studio in Europe. He even tried American studios. Half the studios complained that the screenplay was not put together well, while the other half summarily declared that they could not understand the story.

Benni Zenabu’s style of storytelling belonged to the post-dadaist tradition. The story progresses in bits and pieces without an overarching connection. But the story had a definitive political undercurrent. Finally, he found the support of an independent film studio in Berlin. He filmed ‘Sweet Pirates’ on a shoestring budget with the little funding he had been able to muster.

With a small film crew and six English actors, Benni went to Somalia and recruited the remaining actors there. He completed filming in a mere twenty-eight days and returned to London.

The basic story was about how the pervasive poverty in Somalia drove little boys to become enamored with pirates and join them. But Benni certainly did not just stop there. In a piece-wise fashion, he inserted the message that Europeans were the first and the foremost pirates in history. The European press completely rejected the movie. They wrote, ‘Director Benni has only a piecemeal understanding of history.” They said that colonialism was inevitable in the relentless march of history. Some left-leaning newspapers invoked Karl Marx in support of their theory.

On the other side, Benni received death threats from Somali pirates. They accused Benni Zenabu of being a black traitor who had revealed their trade secrets to the white man. Thanks to the efforts of the Berlin studio, the movie was screened at some film festivals. Although the movie received some praise from discerning film enthusiasts, it was unable to recover the money that was invested into making it.

When he was thirty-eight, Benni shot his second film, Zarathushtra. An English studio produced this film at great expense. It was the story of a great sage from ancient Persia. In this historical saga, Jesus, Buddha, and the Prophet Mohammad, all appear as ordinary people.

That year, the Iranian government had been feeling dejected that no Iranian movie made it to international film festivals. They were concerned about it more than the film festival directors were. But when Benni’s film that had a historical connection to Iran was released, the Iranian government regained its enthusiasm and promptly banned the movie. It also banned Benni Zenabu forever from entering Iran.

It was indeed a great movie. Benny’s mastery of the art shone through this film. Although it was not a great commercial success, it won him accolades as one of the best directors in the business. An English newspaper dubbed him, ‘Black Stanley Kubrick.’ Benni responded by saying ‘Fuck off.’

When Benni read Barbara Brickman’s ‘Bad Word God,’ he decided that it would be his next movie. He met Barbara immediately. Through Barbara, he met Teacher Sathāsivam, the founder of the ‘London Jaffna Swami Sath Sangam. As he talked with Sathāsivam, the film began to grow in Benni Zenabu’s imagination.

This is how he wrote the sketch: The war in Sri Lanka, the secret liaison between the war and the imperial powers, the Sri Lankan government with its penchant for violence, the armed militant groups that sprouted in response, the mystic called Jaffna Swami, his voice against the war, his conversations that made fun of those in power, his transmutation of words that society considered to be dirty words into holy words, the image of a covert mystic.

As he thought more and more about the subtleties of this story, Benni reached the peak of artistic ecstasy. He made only one addition to the screenplay that was not in Barbara’s book. In the last scene, the bullet-ridden body of Jaffna Swami was seen floating away.

After his earlier movie, Zarathushtra, big production houses were very keen to produce Benni’s next film. But Benni wanted to be independent, without being bound by the commercial constraints of the big production houses. The British National Television Corporation came forward to partly fund his new movie. But the funding they were willing to provide did not even amount to ten percent of the required investment. Benni raised the rest as loans from his friends. The ‘London Jaffna Swami Sath Sangam’ made a modest contribution of 5001 pounds to Benni.

Sathāsivam believed that this movie would make Jaffna Swami’s greatness spread all over the world. Therefore, he extended his full cooperation to Director Benni. More than sixty percent of the dialogue in Benni’s screenplay needed to be spoken in Tamil. Teacher Sathāsivam took on the responsibility of translating the original English dialogues into Tamil. He viewed this as his great divine service to Jaffna Swami. He took a three-month leave-of-absence from his job and completed translating the dialogues into Tamil.

The next phase was to search for actors. Benni was firm in his decision to introduce fresh faces as actors in this movie. Jaffna Swami was the only lead character. The remaining Tamil and Sinhala characters were extras. Benni decided to cast the extras in Sri Lanka itself. Assistant Director Elisa was ready to play the role of Barbara. But he needed a talented actor to play the role of the Swami. The actor should be able to play the character from twenty-years to forty-years of age. Since the character did not have a lot of dialogue, the ability to act with body language played a big part.

Benni searched everywhere in Europe for a Sri Lankan Tamil actor whose appearance resembled Jaffna Swami’s. There was no Tamil student in any of the film institutes. Without any hint of irony, Sathāsivam, who accompanied Benni in his search, proudly declared, “Our people don’t send their kids to study acting; we send them to study only engineering or medicine.” The only Tamil student in a Paris acting school did not know either Tamil or English. Besides, the boy weighed a hundred kilograms. He was not fit to play the gaunt Jaffna Swami.

Benni thought he might be able to find a suitable actor from among those who are part of the Tamil theater groups run by twentysomething Tamil youth. But when Benni learned that there was no such theater group in all of Europe, he was at a loss to understand why. Sathāsivam said, “There is an old Tamil proverb ‘Acting and miming is the last resort for the incompetent’,” further confusing Benni.

Left with no other option, Benni escalated to the next step. He used a casting agency to place an advertisement saying, ‘Seeking a Tamil-speaking actor.’ Only five or six people applied. Sathāsivam was fueling Benni’s irritation by observing, “Our people will not pay heed to such ads.” Among the applicants, Benni liked a thirty-year old young man called Nēsaṉ. He had arrived in London from Sri Lanka only five years prior. So, he spoke perfect Jaffna Tamil. During the interview, Benni was reasonably satisfied with Nēsaṉ’s acting skills. He was confident that with some acting training, Nēsaṉ could be prepared to play the role.

A date was fixed to travel to Sri Lanka for the shooting. The Sri Lankan government granted only a 45-day permit for the shooting. Even that required bribing at many levels. Production managers had traveled to Sri Lanka to make all the necessary advance preparations.

Benni was holding eight-hour daily acting training sessions for Nēsaṉ. Two days before the film crew was to travel to Sri Lanka, Nēsaṉ disappeared. Benni and Sathāsivam tried to call Nēsaṉ repeatedly, to no avail. When they were at a loss as to what they could do next, Sathāsivam received a call from Nēsaṉ. Sathāsivam almost wept.

“Thambi Nēsaṉ… we have to travel to Ceylon the day after tomorrow. You went missing all of a sudden.”

“Yes, aiyā, there is a small problem.”

“What problem? Don’t you have a Sri Lankan passport? You won’t have any visa problems.”

“It is a different problem, aiyā… you know that there is a sex scene in the movie. The Swami and the white woman do it naked at Elephant Pass. My fiancé does not want me to act in that scene. We are getting married in three months.”

“Thambi.. You are just going to act. You won’t have to do anything for real, will you? It is just a movie.”

“Aiyā, for you it is just a movie. For me, this is life. Please forgive me. Vaṇakkam.”

Sathāsivam rushed to break the news to Benni. Benni was crushed. They had only thirty hours before departure. Was it realistic to find a replacement actor in such a short time!

Benni closed his eyes and immersed himself into deep thought. He kept imagining Jaffna Swami’s gaunt face and drowsy eyes. Suddenly he started to feel as if he had seen them firsthand. He hit his forehead repeatedly with his broad fat palm when he realized that the face he kept seeing was the face of Omkar Bhushan.

Omkar Bhushan was a Marathi. He belonged to a small theater group in London. He had met Benni a few times to ask for an acting opportunity. His face and body was just like those of Jaffna Swami. His skin color, too, was jet black.

Within eight minutes of receiving a call from Benni, Omkar was in Benni’s office. Benni gave Omkar the script for the Elephant Pass scene and asked him to act it out. When Omkar looked at the sheet of paper with the dialogue, Omkar did not even think of asking which of the two characters Benni wanted him to act out. He acted through the scene, taking turns playing the Swami and Barbara. Sathāsivam, who was watching all this from the sidelines, started to tear up, overcome with emotion. He felt as if he was watching the divine dance of the artanārisvara, the half-male, half-female form of Lord Shiva. Benni was certain that Omkar was the actor he was desperately searching for.

On the flight over to Sri Lanka, Sathāsivam sat next to Benni. Benni thought of something, tapped Sathāsivam on his shoulder, and asked, “Don’t you think that the Tamil boy Nēsaṉ was a better choice than this Omkar?” Sathāsivam responded thus:

“See Mr. Benni, we had a great poet named Bhārathiyār. He said that among all the languages he knew, there was none sweeter than Tamil. But when they made a movie of his life story, a Marathi played him. If a Marathi can play the greatest of all Tamil poets, would he not be able to play a Tamil mystic!”

Benni patted Sathāsivam’s shoulder with a smile. Carried away by this enthusiasm, he finished the shooting in Jaffna within just forty days and returned to London with the film crew. Within two months, he had the editing and mixing completed, supervising the work day and night. As Benni was pondering which international film festival the movie should premiere in, Sathāsivam came to him with a request.

“See Mr. Benni! I would like to request humbly that this movie be screened at our Sath Sangam next Friday. Disciples of Jaffna Swami, some Tamil journalists, and some Tamil intellectuals are all eager to see the movie.”

Benni smiled at Sathāsivam and said, “This is your film. Your life. I am merely an instrument. We can certainly screen the movie there.” On Friday evening, within a few hours after the movie was screened at the hall of the London Jaffna Swami Sath Sangam for a select list of invited guests, complaints about Benni Zenabu started flooding the Internet.

A series of accusations were put forward, that the Tamil pronunciation in the film was mangled, that the lead character was not played by an Eeḻam Tamil actor but by some Marathi, that during the shooting, Benni Zenabu had met with a minister of the genocidal Sri Lankan government. It was Sathāsivam who brought these accusations to Benni’s ears.

Benni was not one to be daunted by such condemnations. He was a seasoned veteran having weathered everything from threats by sea pirates, and the ban by the Iranian government, to the racism of white journalists. Although he was not afraid, he was truly sorry to hear about the accusations. He had tried his best to truthfully portray a land, language, and culture that was alien to him, depicting the civil war that took place there. But if the very community he portrayed in the film opposed it, he felt, it meant that he had made a mistake somewhere. He told Sathāsivam that he wanted to meet with the objectors to discuss their concerns and find an amicable solution. A date was fixed to hold this meeting at the Sath Sangam itself.

In his opening speech at the meeting, Benni apologized for not knowing Tamil. He also promised to correct any mistakes in Tamil pronunciation in the movie. Someone heckled, “But what is spoken at many places in the movie is not Tamil!”

Benni looked at Sathāsivam with some discomfort and said, “Our respected Teacher Sathāsivam wrote the Tamil dialogue.” Sathāsivam felt as if he was being stripped naked in public. Already long ago, he had passed the examination to qualify as a Tamil pundit. He had written the dialogue in grammatically correct, literary Tamil. When Omkar spoke the words in the movie, they sounded right to him. But when he listened to the same on the big screen at the movie theater, he did notice occasional lapses. Sathāsivam sat quietly, wringing his hands. Benni promised again, “We will correct the dialogue before releasing the movie to the general public.” Trying to bring about a conciliatory mood, he smiled and said, “If any of you have experience in dubbing, you could come forward to help us.”

One person threw a new accusation, “It is ok if Tamil was spoken incorrectly, but Sinhala was spoken in the guise of Tamil.” Startled, Benni looked at Sathāsivam piteously. Sathāsivam asked in a faint voice, “That couldn’t have happened… which dialogue did you have in mind?”

The accuser said, “In many places, we hear muyaṅga … muyaṅga.”

Sathāsivam understood the problem. In the original English version of the script, Benni had written ‘Fuck Fuck Fuck’ in pretty much every page. Sathāsivam had translated that into pure Tamil as ‘muyaṅga… muyaṅga … muyaṅga.’ Sathāsivam said, “It is indeed Tamil.” The accuser responded with dissatisfaction, “I know Jaffna, Batticaloa, Colombo, and every other variant of Tamil. I had never heard such a newfangled Tamil.”

The next angry question was lobbed at them, “Why wasn’t an Eeḻam Tamil actor cast in the role of the Swami?” Benni looked as if he was about to cry. He folded his fat hands at his chest and said, “I tried… but I was unable to find one.”

“Ho,” the entire hall let out a sigh of dissatisfaction, followed by another voice saying, “You should have tried harder.”

“Mr. Benni Zenabu! Why did you meet the Sri Lankan minister when you were in Colombo?” asked a young man.

“We have to meet them in order to get permission to film, my friend. I couldn’t have filmed this movie in England, could I? It is not just me. Many foreigners go to Sri Lanka to shoot movies. Furthermore, many Sri Lankans produce movies themselves. Everyone has to seek permission from the government.”

Someone else piped up, “We cannot accept the scene where the Swami is being assaulted. It hurts our feelings.” Benni asked, “The assault on the Swami at the torture camp becomes the turning point in Swami’s life… how could we dispense with that scene?”

“We know that. I am talking about Swami being assaulted when he was a young boy…”

At the beginning of the movie, there was scene in which the ten-year old Nāgēsvaraṉ was playing cricket. His mother slapped him on his back, saying “Go study.” Sathāsivam thought to himself, ‘If we take a movie about a cricketer hitting a cricket ball, their feelings would be hurt; if we take a movie about a cricketer being hit, their feelings would be hurt.’

A lady stood up, looked around, and launched into a long speech: “Mispronouncing Tamil in this film is not an ordinary problem. It is linguistic politics. You are further oppressing an ethnic group that has been long oppressed. Jaffna Swami is an important cultural icon for us. You may not have known about the bhakti movement. It was a movement that rose up in response to Hindi hegemony. There are thirty-five saints in our tradition. Jaffna Swami can be considered the thirty sixth…”

As the lady held forth, Sathāsivam remained steadfastly quiet. But his darned tongue did not. He interrupted the lady to say, “Not thirty-five… sixty-three.” The lady said, “Different people come up with different estimates for the number of saints. The conservative estimate is thirty-five,” and continued. Sathāsivam mumbled sadly, “For seventy years since the day I was born, I have been worshiping sixty-three saints.” When Benni looked quizzically at Sathāsivam, the next voice boomed, “Look here Mr. Benni!”

“In the last scene, Jaffna Swami’s bullet-ridden body is shown. Who shot the Swami?”

Benny thought for a moment and said, “I don’t know.”

“Ho,” the hall roared again with dissatisfaction, even more loudly than the last time.

“Listen Benni Zenabu. You cannot film as you wish under the guise of artistic license. Did you think that no one would question you? We firmly believe that the Jaffna Swami will return. We will boycott your movie!” The voice was shaking with emotion. The meeting ended there.

A group of intellectuals wrote to film festivals to express their dissatisfaction. Objections were raised that the tax revenue from the three hundred thousand Eeḻam Tamils living in Britain had been wasted. Intellectuals published a letter in prominent English newspapers demanding that the British National Television Corporation must reclaim their grant to this film. All of this culminated in the demand that Benni Zenabu should issue a public apology for having made this film. Benni lost his patience and locked himself up in his room.

The Somali tribe Yibir are known for their bravery and martial skills. They never surrender in battle. Benni Zenabu who came from this tradition, writhed in anxiety not knowing how to control himself. At the height of his anger, he tore off his clothes, leaving his body completely naked. The six-and-a-half foot Benni was hopping around in his room unable to let his fat body stay on the ground. Then, spreading his long arms, and curving his back, he stalked his room like a fierce animal. His breath was piping hot. His eyes were drowsy. At that moment, he recalled the words of Jaffna Swami: “more wakeful than the wakeful, soiled flower offering.” (sākkirattil sākkiram eccil pū kāṇikkai.) He started mumbling those words repeatedly.

For a few days after director Benni Zenabu disappeared from England, his disappearance dominated the news. The police forces half-heartedly did a cursory investigation and were only relieved to close the file on this case. The only person who knew everything that had transpired was Sathāsivam.

How did Benni Zenabu who disappeared from England suddenly appear in Jaffna? How did he become an ascetic wearing only a loincloth? What was the psychology behind the people ecstatically accepting that their long-awaited Jaffna Swami had indeed reappeared in a different form? But I had a question that was more important for me than all of these questions.

I asked my mother on the phone:“Ammā… how is the Swami able to speak in Tamil… do you understand when he speaks?”

“Why? What is wrong with his Tamil? He speaks in a flurry of fluent obscenities. Even your appā couldn’t speak as fluently using expletives. Practice makes perfect in Tamil just as it does in painting,” said ammā.

November 2020