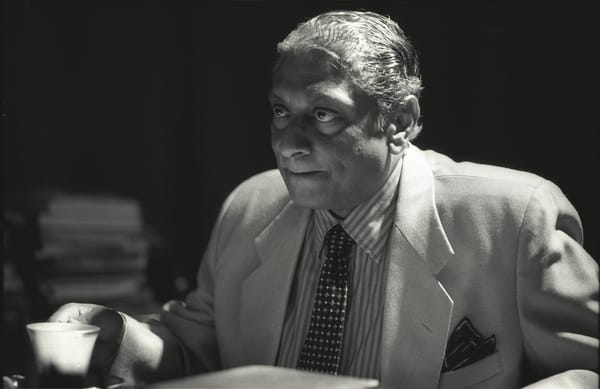

The only reason the Tamil Tigers managed to assassinate Sri Lanka’s erudite Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar is because his inept security didn’t anticipate that a sole sniper would carry out the mission impossible.

It was another excellently executed cold-blooded murder that only the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) could have pulled off, humiliating a seemingly impenetrable security ring which had turned Kadirgamar into Sri Lanka’s third most protected individual.

But even as the 73-year-old man slumped after taking three bullets while stepping out of his swimming pool an hour before midnight, it was clear that Kadirgamar had more than succeeded in his mission of choking the LTTE where it mattered: the normally unfriendly and sceptical West.

More than anyone else, it was the scholarly politician’s uncompromising single-point war of ideas that seriously hurt the LTTE. Thanks to Kadirgamar’s tireless efforts, the US (1999) and Britain (2001) outlawed the Tigers, crippling the group’s ability to raise funds for its unending war and making the “liberation group” a pariah in two countries which mattered.

And once it became known that the LTTE, its usual denials notwithstanding, was to blame for the assassination, Canada and the European Union too followed suit, dealing a massive blow to the Tigers. Finally, less than four years after Kadirgamar died, the LTTE was militarily crushed, its insolent leadership was wiped out, and the dream of carving out a separate Tamil Eelam state lay shattered.

But it would have been far better for Sri Lanka had Kadirgamar been alive post-LTTE because he would have surely prevailed upon the then government not to become triumphalist after the war and instead forge an ethnic unity of minds that still eludes the island nation.

This is one of the key takeaways from the just published fifth edition of The Cake That Was Baked at Home, a heartfelt and eminently readable tribute to Lakshman Kadirgamar by his family, friends and admirers and put together by his only daughter, Ajita Kadirgamar. The book clears many cobwebs surrounding a man who was both admired and vilified.

A Protestant Christian by birth, Kadirgamar was eclectic in religious thought. He read both Buddhism and Hinduism extensively. But he firmly rejected the ethnic tag of being a Tamil and repeatedly underlined that he was a Sri Lankan first, a Tamil and a Christian next.

Naturally, large sections of the Tamil society, including those who should have known better, ridiculed him as a token Tamil and, worse, a traitor. The latter label came from the LTTE, whose word could not be challenged when it held sway. He was accused of ignoring Tamil grievances and whitewashing the aggression of Sinhalese nationalists as well as the military atrocities on Tamil civilians.

However, Kadirgamar was proud of his Tamil roots although he could not speak the language fluently – and neither the Sinhala language. He was at home in English. He was deeply concerned about Sinhala being made the sole official language. He believed that human rights violations were wrong, for more reasons than one; as minister, he quietly helped Tamil lawyers to secure compensation to Tamil victims of military high-handedness. Although not a Tamil nationalist, he had high regards for the founding fathers of the Federal Party.

He believed firmly that Tamil separatism had its origins in some real grievances over language and other issues. He played a key role in re-establishing the glory of the Jaffna Public Library, a Tamil institution of immense pride which pro-government vandals set fire to and destroyed. But he would not condone terrorism, including the methods used by the LTTE. Whatever little faith he had in a negotiated settlement with the Tigers was rudely shattered after the LTTE resumed its war in 1995, a year after he became the foreign minister at age 62.

Kadirgamar’s relentless campaign against the LTTE, particularly with Western governments, ended up showing him as an apologist for Colombo. That he was effective in his mission is what riled the LTTE. As is their wont, the Tigers first sent word to him – as they did to Rajiv Gandhi much earlier – that he would not be harmed. But the LTTE tried more than once to kill him. He was to be present at the election rally in 1999 where a LTTE suicide bomber blinded President Chandrika Kumaratunga. There was also a plan to run a high-voltage electricity wire through a heated swimming pool when he would use it during a visit to India.

Kadirgamar knew he was a prime target of the LTTE. His house and office naturally became a fortress – and a prison. His social life came to a halt, upsetting many of his friends and relatives, some of who could not appreciate the gravity of the situation. If he went out, there would be as many as 16 identical vehicles in the convoy to confuse would-be assassins.

By the time his end came, Kadirgamar perhaps realised that he did not have a long innings. He turned philosophical. He knew his life was in danger but he could be careful only up to a point. A friend who met him before his death thought he had become a sadder, quieter and emptier version of his original self. He told a friend: “I have reached an age when I don’t have many more years to live. The time may come when they may finish me. I can’t help it. I have some work to finish and I must not give up.”

Neither Kadirgamar nor the LTTE gave up. Given the determination on both sides, it was but natural that the ruthless Tigers would come on top. But as the LTTE and its leadership realised too late the immense self-goal they scored by assassinating Rajiv Gandhi, they did not gauge what Kadirgamar’s killing would do to them.

Such was his global stature – although he represented a small country – that the Oxford-educated man’s assassination triggered widespread revulsion. Whatever sympathy the Tigers may still have had in some Western capitals was gone. Naturally, Sri Lanka felt confident to take on the LTTE the next year in Eelam War IV which led to the group’s unimaginable destruction, unfortunately at the cost of thousands of lives, dominantly Tamil civilians.

Did the LTTE kill Kadirgamar because he was anti-Tamil? That was a spurious excuse. Velupillai Prabhakaran had him done away with because he had become a huge and painful thorn for the LTTE. The entire overseas LTTE lobby could not stand up to Kadirgamar. That he was a “traitor” was simply an appellation; a label that Prabhakaran could flung at anyone he wanted killed.

Of course, for whatever he did for the Sri Lankan establishment, many Sinhalese politicians did not want to see him as Prime Minister. No one said why but his ethnicity was obviously a roadblock. At one time he did feel he would get the post; Kumaratunga too rooted for him. But Mahinda Rajapakasa, who eventually oversaw Prabhakaran’s killing, was firmly opposed to Kadirgamar and himself became the Prime Minister. The lack of chemistry between the two men was evident in Mahinda’s conduct at Kadirgamar’s final rites.

Kadirgamar was, however, plagued by a personal crisis. After he divorced his first wife, a French citizen (not a Tamil), he married a Sinhalese lawyer who forbade him from having any contacts with his children from the first wedding. Ajita Kadirgamar writes about the trauma she and her brother underwent in the process more than frankly in the thick book. After he re-married, he failed as a father, she says. “We stood in the wings helplessly as first another woman and then a whole nation hijacked him as their own.”

Professionally, Kadirgamar was thorough. He restructured the foreign ministry and put an end to political appointments. He was friendly towards India but did not want to hitch Sri Lanka’s foreign policy to New Delhi’s. He respected the UN but did not want it to poke its nose in Sri Lanka’s internal affairs. He despised the LTTE but turned down an offer by an agent of a foreign mercenary group to “take out” a key LTTE leader abroad who was in charge of procuring weapons for the Tigers.

Perhaps, his stature diminished slightly towards the end of his political career. This is when he mounted a spirited attack against the ceasefire agreement signed with the LTTE with Norway’s facilitation. In the process, he became a weapon Chandrika Kumaratunga used to attack Ranil Wickremesinghe, who signed the pact. It was a price Kadirgamar paid for being in politics in a country where even monumental crises fail to elicit a national consensus.

This book should be a must-read if you need to understand Kadirgamar better.

Title: The Cake That Was Baked at Home: Laskshman Kadirgamar; Author: Ajita Kadirgamar

Publishers: Vijitha Yapa (Sri Lanka)

Pages: xxv + 586

Price: Rs 4,400 (SLR)