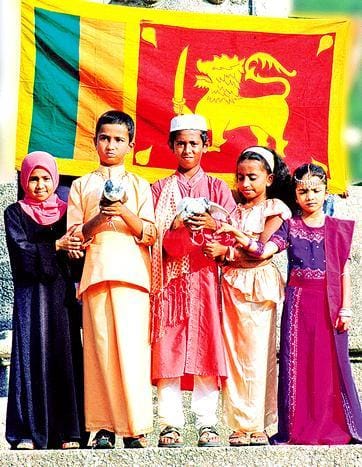

Opposition MP and President's Counsel Faiszer Musthapha has submitted a Private Member Bill to Parliament seeking comprehensive reform of Sri Lanka's Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA), marking what legal experts describe as the most far-reaching reform effort in decades to address discriminatory provisions affecting Muslim women and children.

The Muslim Marriage and Divorce (Amendment) Bill, submitted to the Secretary-General of Parliament Kushani Rohanadeera today, proposes sweeping amendments to legislation enacted in 1951 and largely unchanged for more than seven decades—despite repeated calls for reform from women's rights advocates, legal experts, and segments of Muslim civil society.

Ending Child Marriage

The bill's most consequential provision proposes 18 years as the minimum legal age of marriage, addressing what rights advocates have long characterised as state-sanctioned child marriage under the existing law.

Section 23 of the current MMDA allows the registration of marriages involving girls below the age of 12 with the authorisation of a Quazi—a state-appointed Muslim judge under the Act—effectively leaving Muslim girls without a clearly defined statutory minimum marriage age.

“The minimum age of marriage under the MMDA is, in practice, undefined,” said a Muslim women’s rights researcher who has documented child marriage cases in Sri Lanka. “This reform has been demanded for more than three decades.”

According to the Unequal Citizens study published by the Muslim Personal Law Reform Action Group (MPLRAG), child marriages involving girls aged 14–17 continue to be reported in districts such as Puttalam and Batticaloa. The study cited official records indicating that in Kattankudy, 22% of registered Muslim marriages in 2015 involved brides under 18, up from 14% the previous year.

Women's rights advocates note that the practice cuts across socio-economic lines, occurring not only in rural communities due to poverty or perceived security concerns, but also in urban areas for cultural and religious reasons.

Mandatory Consent and Appointment of Women Quazis

The bill introduces a requirement that brides must sign the marriage register, addressing a longstanding gap in the law. Under the existing MMDA, a woman's signature is not required for a marriage to be legally registered, raising serious concerns about consent.

In a landmark reform, the bill also opens the office of Quazi to women for the first time. At present, all 65 serving Quazis are men, and women are explicitly excluded from appointment. The proposed amendment would further require newly appointed Quazis to hold qualifications as Attorneys-at-Law, raising professional and ethical standards within the system.

Legal Representation and Court Jurisdiction

Another key reform allows legal representation in Quazi Courts, a right currently denied to litigants. Women's rights organisations have long documented cases of discriminatory rulings, verbal abuse, and procedural unfairness in proceedings where women appeared without legal counsel.

In a 2023 report, the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) noted that Muslim women's access to justice is "severely limited" by the prohibition on both women Quazis and legal representation.

The bill also proposes transferring maintenance claims from the exclusive jurisdiction of Quazi Courts to Magistrate's Courts, bringing such cases under the general Maintenance Ordinance and aligning them with the broader legal framework applicable to all citizens.

Decades of Failed Reform Attempts

Musthapha's initiative comes after multiple failed reform efforts spanning several decades, including major initiatives in the latter half of the 20th century and again in 2009—many of which collapsed amid resistance from conservative Muslim organisations, particularly the All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama (ACJU).

In 2019, following the Easter Sunday attacks, Muslim MPs reached consensus on key reforms—including raising the marriage age to 18 and permitting women Quazis. However, civil society groups later alleged that sustained pressure led to those recommendations being diluted before Cabinet approval.

The Cabinet-approved proposals have remained with the Legal Draftsman's Department since August 2019, with no public update on progress.

Support and Anticipated Resistance

Legal experts, women's rights advocates, and civil society groups have welcomed Musthapha's proposals as "long overdue" and consistent with contemporary social realities and child protection standards.

"Setting 18 as the minimum age of marriage is not about religion—it is about protecting children," said one women's rights advocate. "Education, health, and long-term wellbeing are at stake."

However, the historical pattern suggests resistance will be swift. Conservative elements have argued that a fixed minimum age contradicts Islamic jurisprudence—claims contested by Islamic legal scholars who maintain that Islamic tradition permits protective safeguards for minors.

MPLRAG has previously warned against reform efforts that prioritise political consensus over the lived experiences of Muslim women and girls.

Companion Divorce Reform Bill

Alongside the MMDA amendment, Musthapha also tabled a second Private Member Bill—the Dissolution of Marriages on the Ground of Irretrievable Breakdown Bill—which seeks to introduce no-fault divorce into Sri Lankan law for the first time.

The proposal would amend the Marriage Registration Ordinance and the Civil Procedure Code to permit divorce where a marriage has irretrievably broken down, without requiring proof of matrimonial fault. It includes provisions addressing maintenance, property division, and child custody.

Legal professionals have long criticised Sri Lanka's fault-based divorce system as adversarial and outdated, arguing that it incentivises false allegations and burdens the courts.

International Obligations and Legal Disparity

Sri Lanka ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1981 and its Optional Protocol in 2002. The UN Committee on CEDAW has repeatedly urged reform of the MMDA.

Under the General Marriage Registration Ordinance and the Kandyan Marriage and Divorce Act, the minimum marriage age was raised to 18 in 1995. The MMDA remains the only personal law framework exempt from this standard.

Uncertain Parliamentary Path

As a Private Member's Bill, Musthapha's proposal faces an uphill parliamentary path, with passage unlikely without government backing. Yet advocates remain cautiously hopeful.

The bills now await placement on the parliamentary order paper. Whether they will finally break decades of legislative inertia—or join the long list of failed reform attempts—remains to be seen.

For thousands of Muslim women and girls across Sri Lanka, the outcome could be transformative.