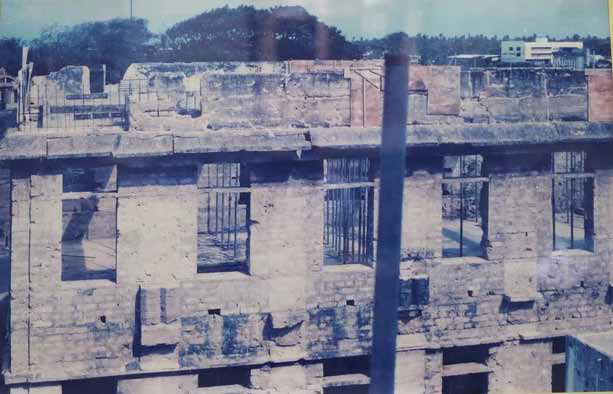

In the decades since the Jaffna Public Library was reduced to ashes-its nearly 97,000 books and manuscripts deliberately set alight in what remains one of the most egregious acts of cultural genocide in Sri Lankan history-a quiet yet determined renaissance has taken root. A new generation of Sri Lankan Tamils, both at home and across the diaspora, has come together to build a library that no racist mob can ever burn again.

That library is Noolaham.org-Tamil for "repository of books." Today, this expansive digital archive holds more than one and a half times the number of documents, books, and rare manuscripts that once lined the shelves of the destroyed Jaffna Public Library.

More than just a collection of texts, Noolaham.org stands as a defiant digital middle finger to the state-sponsored arsonists and chauvinist forces who once tried to incinerate a people’s memory and intellectual heritage. This vital digital repository of Tamil knowledge cannot be looted, cannot be banned, and certainly cannot be set ablaze. It's a defiant act of preservation, ensuring that the rich tapestry of Tamil culture and intellect endures, unyielding against the flames of oppression.

The First Sparks of a Digital Renaissance

In the 1990s, as computers began to flicker to life across South Asia and its diaspora, a quiet digital awakening was taking root among Tamil scholars and tech enthusiasts. Inspired by global initiatives like Project Gutenberg, a handful of Tamil visionaries began to imagine a future where their literary heritage could be preserved online.

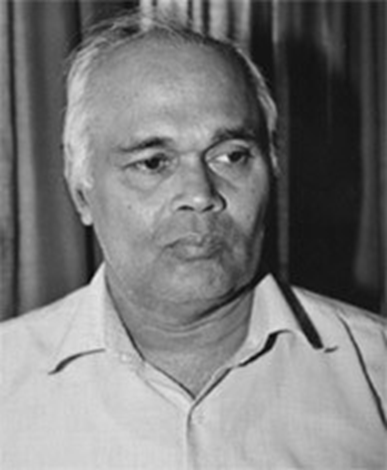

The turning point came in 1998 with the launch of Project Madurai-the first online Tamil digital library, modeled after Project Gutenberg. It was a modest, volunteer-driven initiative, but it marked a bold leap into the digital era. A year later, in 1999, R. Pathmanaba Iyer, widely regarded as the pioneer of Sri Lankan Tamil digitization, began digitalizing Sri Lankan Tamil books. He digitized 40 titles-13 of which were later contributed to Project Madurai, marking the earliest known integration of Sri Lankan Tamil literature into a global digital archive.

In the early 2000s, with growing access to personal computers and the internet, Small but determined projects like Eelanool and E‐Suvadi emerged between 2004 and 2005, quietly digitizing Sri Lankan Tamil publications with whatever tools, time, and bandwidth their volunteers could muster. These efforts were scattered and largely uncoordinated-but their importance was undeniable. Together, these early experiments lit the path toward something far more ambitious and enduring.

The Birth of Project Noolaham: A Community’s Digital Leap

In January 2005, a new chapter in the preservation of Sri Lankan Tamil heritage quietly began with the launch of Project Noolaham, founded by Thillainathan Kopinath and Muralitharan Mauran. The initiative built upon and integrated earlier digitization efforts-most notably the pioneering work of R. Pathmanaba Iyer. It also incorporated the contributions of Eelanool.

By August 31, 2005, the formation of the Noolaham Google Group brought together a vibrant network of contributors, laying the groundwork for what would become a global volunteer movement. Pathmanaba Iyer was appointed an advisor to the project. Others like K.T. Pratheepa, P. Eelanathan, K. Raminitharan, Mathy Kandasamy, L. Natkeeran, and Kanaga Sritharan soon joined. The project also attracted the support of S. Thevaraja, representing the Thesiya Kalai Ilakkiyap Peravai, whose organization agreed to contribute its materials to Noolaham.

To support this growing initiative, Noolaham purchased its first server in August 2005. By the end of 2005, the digitized archive had crossed its first major milestone: 100 books preserved and accessible online.

They Were Born When the Library Burned

When asked how it came to be that many of the founders of the Noolaham initiative were of a similar age, Kopinath offered a reflection.

“Those who worked with us-Eelanathan, Natkeeran, Mayuran, myself, Shaseevan-we were all roughly the same age. Born within a few years of each other, between 1980 and 1982,” he told Jaffna Monitor. “When you ask that question, it strikes me-we were all born around the time we lost the Jaffna Public Library.”

“We were in our early twenties in the early 2000s. Coincidentally, that was when computers-though still expensive-were becoming just about accessible. Unicode was gaining ground, and around 2001, Wikipedia entered the scene. We were the right age, at the right time.”

“That was when we were just getting introduced to computers, learning to type, and experimenting with platforms like Blogspot. If we had been 15, we’d still have been in school. If we’d been 25, we might have been caught up with jobs, families, and responsibilities. But at 20-you feel that drive, that energy to start something. To act.”

The Bold Reinvention of Noolaham

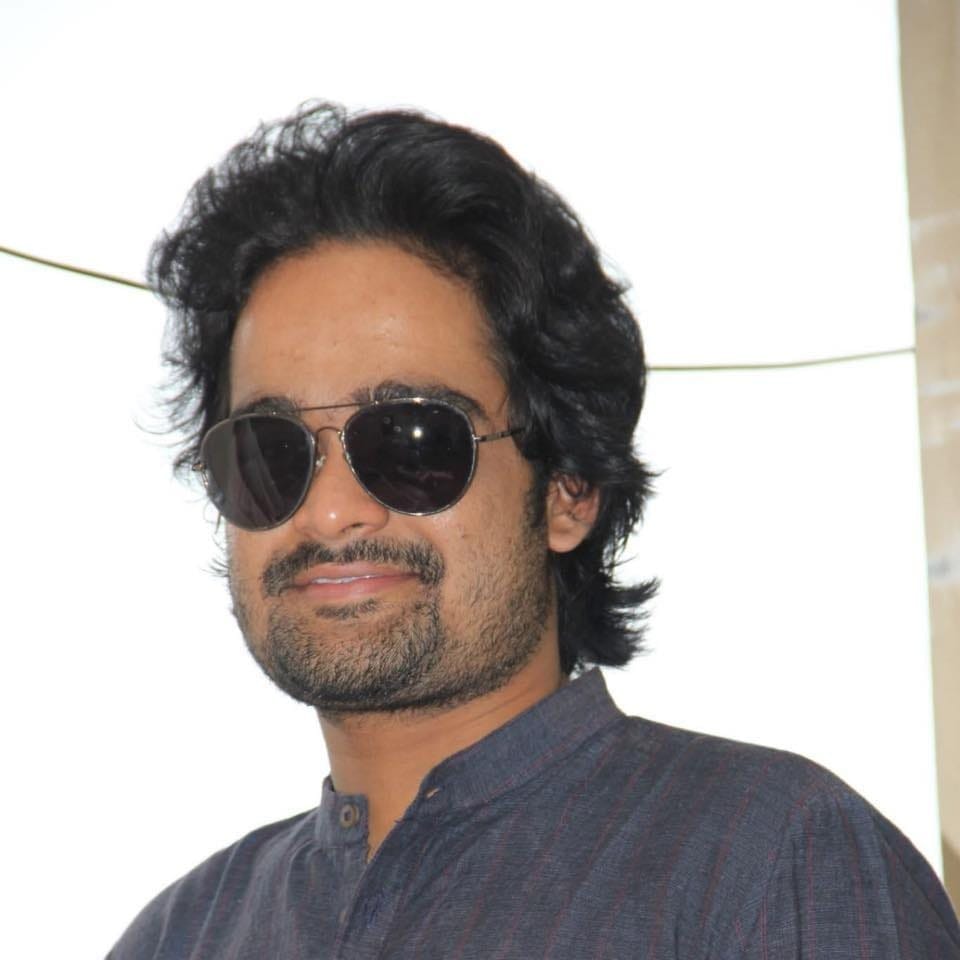

The man widely credited with transforming Noolaham from a volunteer-based initiative into a formidable institution is Shaseevan Ganeshananthan, now a software entrepreneur living in the UK. Speaking to Jaffna Monitor, he traced the turning point back to his school days.

“Kopi-Thillainathan Kopinath-and I were classmates at Jaffna Hindu College from the sixth standard. After our A/Ls, we even brought out a little magazine together called இசை புதிது -A New Direction,” he recalled. “In 2006, just as Project Noolaham was finding its feet, Kopi had to leave for Malaysia to pursue higher studies. It became painfully clear to us that if Kopi left, the entire project could grind to a halt.”

Though Shaseevan had previously volunteered with Noolaham, it was only in July 2007, that Kopinath formally handed over the coordinating role to him. “In my mind,” Shaseevan said, “if something has to be done, it must be done in a structured way. One of the biggest problems I see in our society is that good initiatives-especially those driven by community passion-remain small because they’re not structured. They’re not institutionalized. So they can’t scale.”

The Birth of the Noolaham Foundation

Shaseevan set about transforming Noolaham from a purely volunteer-run effort into a structured, project-centered organization. For the first time, the idea of paid staff was introduced. Until then, every single page had been digitized by volunteers working from homes, rooms, hostels, and sometimes even internet cafés.

But such change didn’t come without resistance. “There was pushback internally,” he admitted. “And I understood where it came from. Around that time, the global conversation was heavily influenced by models like Wikipedia and the Free Software Foundation. They stood for flat hierarchies, pure volunteerism, and anarchic collaboration. Many within Noolaham were drawn to that ethos and wanted to preserve it.”

“But once you start institutionalizing,” he added, “hierarchy becomes inevitable. You need structure."

Thankfully, Kopi supported the shift. He had spent years manually digitizing books-typing and scanning them page by page. He understood the amount of labor it took.

Then came an idea that somewhat rewrote the script. “With donations, we bought 16 scanners each costing about Rs. 3,000 at the time,” Shaseevan explained. “We gave them to 16 university students, with one condition: each had to scan 3,000 pages. Once they met that target, the scanner was theirs.”

It was a simple bargain-but it worked like magic, Shaseevan explained to Jaffna Monitor. “At that point, we didn’t even have a proper office, But that one move brought in a new kind of energy. The students took ownership. The digitization rate exploded. The project had found its second wind.”

By the time 2007 drew to a close, the numbers told their own story. When Shaseevan took over, Noolaham had 406 digitized books. By the end of the year, that number had ballooned to 1,618.

The methods evolved too. “We introduced editing and post-processing,” he said. “Earlier scans were often raw-some pages crooked, some smudged. We cleaned them up. We made sure what we published was readable and complete. If we digitized a book, we also tried to track down related material.” What came next was the biggest leap yet. “Until then, we were mostly scanning literary works,” he said. “We asked-why stop there? Why not preserve magazines, newspapers, research papers, and even event souvenirs? Why not build a complete record of Tamil printed history?”

And so, in 2008, the project took a bold new turn. Shaseevan laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the Noolaham Foundation. That same year, the Foundation’s first Board of Trustees was formally appointed, with R. Pathmanaba Iyer serving as Chairperson, Shaseevan as Coordinator, and five others-including Kopinath-contributing as directors. In May 2010, the initiative was officially registered under GA 2390, marking the formal birth of the Noolaham Foundation.

"Giving Everything to Everyone”: How Noolaham Challenges Tamil Norms Around Knowledge

“What sets our library apart-perhaps the most significant aspect-is that we went against a deeply ingrained Tamil mindset,” explains Kopinath. “We made everything open access. Free for everyone. In truth, the idea of openly sharing information has never been part of Tamil culture. We tend to be hoarders of knowledge-guarding it, preserving it, but not necessarily sharing it.” Noolaham was built in direct opposition to that mentality. “We’re here to give everything to everyone,” he says.

“Every society functions in its own way. In our community, knowledge has traditionally been passed down through songs, stories, and oral traditions. That’s how it reaches the next generation. So, I wouldn’t say we entirely lack a documentation culture-but it’s certainly not strong or structured". "We’ve never really had a comprehensive, archival approach to preserving our collective memory.” “But today’s world operates largely within a Western framework,” he continues. “If we want our history and identity to survive-and to be acknowledged-on the global stage, then we have to engage with that model of documentation.” “That’s exactly what we did,” he told Jaffna Monitor.

“What About Us?”: The Missing Archive of Our Own Pain

Take Australia, where I now live,” says Kopinath. “White settlers committed massacres against Aboriginal people, carried out atrocities, and implemented the ‘Stolen Generations’ policy-where Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families and raised in white institutions. But there was extensive documentation. That’s why today, their genocide is acknowledged: the evidence exists.” “But what about us?” he reflected. “What have we documented about 2009? Even now, we haven’t done it right.”

Roadmap 2020

In 2012, Noolaham developed its first Strategic Plan (2012–2014) alongside a long term Roadmap-2020. At the heart of that roadmap was an audacious goal: to digitize 97,000 documents by the end of 2020.

At first glance, the number seemed more like a dream than a realistic target. But as Shaseevan explained to Jaffna Monitor, there was deep symbolism behind it. “The Jaffna Public Library was burned with 97,000 books inside,” he said. “So we chose that number not just as a target-but as a way of quietly reclaiming what was lost.”

In 2012, Noolaham had only 12,000 digitized documents. The idea of archiving another 85,000 within eight years felt almost absurd. “We laughed when we drafted the plan,” Shaseevan admitted. “Logically, it didn’t make sense. It had taken us seven years to digitize 12,000 items, and yet we were setting a goal that was seven times greater within nearly the same span.”

But the team did more than dream. “We created a roadmap-a strategic plan with clear timelines, targets, and methods. Looking back now, we didn’t just wish. We engineered a way to get there,” he said.

Against all odds, they did. By the end of 2020, Noolaham had reached the milestone: 97,000 documents digitized-matching exactly the number lost in the burning of the Jaffna Public Library.

Noolaham and the Long Shadow of Jaffna’s Loss

When Jaffna Monitor asked whether Noolaham could be seen as a response to the 1981 burning of the Jaffna Public Library, Kopinath recalled that when Noolaham’s first website (noolaham.org) was launched in 2005, it featured an image of the burned library on its homepage. Although that version of the site is no longer active, the symbolism, he said, was deliberate.

“So yes,” Kopinath told Jaffna Monitor, “whether consciously or unconsciously, the urge to respond to the loss of the Jaffna Library was definitely within us.”

Yet he was quick to draw a distinction. “It would be wrong to say that Noolaham is a direct replacement for the Jaffna Library. There was certainly a communal desire to respond-to protect our records, to build a library that wouldn’t drown in a flood or burn in a fire. That feeling was in the air when we started.”

For many, the destruction of the Jaffna Library remains a powerful emotional trigger. “It’s etched deeply in the collective conscience of our people. You could say it wounded the Tamil soul,” Kopinath said.

But Noolaham, he emphasized, was also born from a deeper realization: the community’s lack of an archival culture. “Our community doesn’t have a strong instinct for documentation. Yesterday’s newspaper is forgotten by today. So our goal became: let’s build a culture of preservation. Let’s archive whatever we can.”

Fundraising, however, has never been easy. “You can easily raise funds for an elders’ home, a school, or a temple,” he noted. “But when you tell someone you’re publishing a book or digitizing old documents, fundraising becomes extremely difficult.” Still, around 400 to 500 individuals continue to contribute financially every year. According to Kopinath, for many of them, the emotional catalyst-the reason they give regularly-is the memory of the burning of the Jaffna Library.

“An Ethnic Duty”: The Moral Imperative Behind Noolaham

Kopinath, Shaseevan, Natkeeran, along with a few others, dedicated the prime years of their youth to building Noolaham. In an era when they could have easily focused on launching private ventures or advancing their careers, they chose instead to invest their time, energy, and talent in a cause larger than themselves. It was a question Jaffna Monitor felt compelled to ask: what drove such a profound commitment?

“It was a critical communal need-to preserve our people’s records, books, and memories,” Kopinath said. “Someone had to step up and take responsibility. Our documents weren’t just lost by accident-they were deliberately destroyed. And sadly, due to our own negligence, documentation has never been a systematic part of our culture.”

Kopinath believes the work of Noolaham fills a longstanding void. “We see it as a vital responsibility-to collect, safeguard, and pass on our people’s records to the next generation. For us, this is an ethnic duty. Even if those involved don’t fully recognize it in the moment, when you step back and look at the bigger picture, that’s exactly what it is.”

He noted that Sri Lankan Tamil society has not historically prioritized archiving or record keeping. “That’s precisely why this work became essential,” he said. “At some point, it felt like holding a tiger by the tail-we simply couldn’t let go. The project had grown so large, so complex, that creating something of this scale again would be nearly impossible.”

He added, “This is a massive responsibility. If a new generation steps up and truly takes ownership, we’ll gladly hand it over and step back. But that moment hasn’t come yet.”

Shaseevan shared a deeply personal story that reveals the extent of commitment and sacrifice that underpinned the project. “When I first took up the responsibility in 2007, my plan was simple,” he told Jaffna Monitor. “I thought I would give two solid years-2007 and 2008-to help stabilize and sustain Noolaham, and then I’d move on.”

But that plan quickly changed. “I ended up staying until 2015 as Executive Director. That was a crucial period in my life, especially in terms of my academic and professional development. I had to let go of my career path in the field I had originally studied,” he reflected. “That’s actually how I moved into business-there was a gap in my professional trajectory because of this commitment.”

We wanted to Build an Ideological Fortress.

“Another reason for doing this was to create an ideological fortress,” said Shaseevan, reflecting on the larger purpose behind Noolaham’s work. “I believe a fortress built on ideas is far stronger than one built with weapons or ethnic sentiment.”

Shaseevan said the vision behind Noolaham was not only to archive documents but to foster a form of activism rooted in knowledge. “Initially, most of what we preserved was literary in nature. But I chose to include Economic Review, the publication of People’s Bank, in our archive. MLM Mansoor-a brilliant banker and Tamil writer-was the Tamil co-editor of that publication. That marked the first time we brought an economic perspective into Tamil archival work.”

He explained how the project matured over time: “We began by archiving literature, then moved into political publications. But literature and politics alone do not define a society. A community is far more complex. Gradually, our scope expanded. It became more diverse and inclusive.” “I believe the knowledge we produce and preserve this way will one day take its rightful, central place in society,” he said.

“What If It Disappears Tomorrow?” The Question of Digital Permanence

Given the painful collective memory of the Jaffna Public Library’s destruction in 1981, a natural question arises: can Noolaham, the digital archive born from that loss, be destroyed too? What if a cyberattack were to wipe it out overnight?

When Jaffna Monitor posed this question to Kopinath, he responded with calm assurance. “Anyone can download the entire digital collection if they wish to,” he said. “In fact, many already have. The content exists in multiple locations, and in some cases, the entire archive has been mirrored.”

Unlike traditional libraries housed in vulnerable buildings, Noolaham is intentionally decentralized. It exists not just as a website, but as a distributed knowledge system safeguarded across multiple formats and geographies. “Our content is backed up in several ways-cloud servers, external hard drives, and even physical storage in secure bank lockers,” Kopinath explained. “Even if the main site were taken offline, the archive would still live on.”

To further protect its holdings, Noolaham has partnered with institutions such as the British Library and maintains backups stored abroad. These offline and international redundancies are part of a comprehensive strategy to ensure continuity, even in the face of cyber threats or geopolitical disruption.

Grassroots Funding and Radical Transparency: The Noolaham Model

In its formative years (2005–2007), Noolaham operated without a formal budget. Volunteers contributed personal equipment, and core expenses-like server and domain costs-were covered out of pocket. As the initiative grew, it began to rely on small-scale donations from the global Tamil diaspora. “Most of our funds come from small donations-$10 or £10 from many supporters,” said one long-time volunteer. This decentralized, community driven model has ensured widespread ownership and helped the archive avoid dependence on any single benefactor.

By 2009, Noolaham formalized a monthly sponsorship scheme, where 12 donors-often cultural associations or alumni networks would each fund a month’s operational costs. Alongside this, the organization began securing institutional grants for specific projects. Support from the Neelan Tiruchelvam Trust, the U.S. State Department, the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP), and the Wikimedia Foundation has enabled major undertakings, including the digitization of palm-leaf manuscripts and multimedia documentation initiatives.

However, Noolaham remains clear-eyed about the limits of project-based funding. As Shaseevan explained to Jaffna Monitor, “There have been historical cases where an entire organization ended up as the de facto property of a businessperson simply because they funded it. We didn’t want that to happen here.” To safeguard its independence, Noolaham ensures that day-to-day operations staffing, infrastructure, and maintenance are sustained by collective fundraising and volunteer-led campaigns, not institutional grants.

Transparency as Principle

Transparency is another cornerstone of Noolaham’s ethos.“We’re open not just financially, but in every operational aspect,” said Shaseevan. “The only thing protected is the admin password-everything else is in the public domain. In doing so, we’ve become a model for other organizations.”

"Just as I was firm about making the library completely transparent, Kopinath was equally insistent that the accounts be watertight-even down to the last rupee," said Shaseevan. "Kopi’s reasoning was clear: anyone can be accused of financial misconduct, so our accounting must be impeccable."

Shaseevan added, “I believed that if we embraced full transparency, things would naturally fall into place. Look at Wikipedia early on, they made everything public, even internal minutes. Open-source organizations also operate with a high degree of openness. That inspired us.”

That commitment appears to have paid off. “To this day, we haven’t faced a single allegation of financial fraud,” another long time volunteer noted. “But still, in personal conversations, people ask us: what’s the benefit of all this? Is there some financial gain involved?” The volunteer explained further: “Among our people if someone is working hard or making sacrifices, the assumption is often that there must be some hidden agenda financial or political. They find it hard to believe anyone would do something purely out of conviction.”

A Global Effort: Diaspora, Volunteers, and Partnerships Fuel Noolaham’s Growth

In many ways, Noolaham functions as a transnational organization. While its headquarters are in Jaffna, its human resources are scattered across the globe, wherever Tamil-speaking professionals reside. Volunteers coordinate through email, WhatsApp, and online forums-and meet in person whenever possible.

“Diaspora volunteers are deeply embedded in our digitization workflows,” said one overseas volunteer. “We have teams based in different countries who collect documents for the Noolaham repository.” In London, for example, a volunteer might salvage Tamil books from recycling centers and send them in. Some rare books have arrived through public libraries, private donors, or even parcels mailed in for scanning.

Members of the Tamil diaspora are also actively involved in governance, fundraising, and technical development. Volunteer hubs have emerged in Canada, the UK, and Australia-organizing outreach initiatives, hosting events, and offering specialist expertise. Notably, the 2007 fundraiser in California and the 2009 event in Australia were led by diaspora groups, underscoring the strength of global Tamil solidarity.

Diaspora professionals have also lent their expertise: IT specialists in Europe assist with server infrastructure, while trained librarians in North America provide guidance on metadata standards. One of the Foundation’s key technology leaders, L. Natkeeran, operates from Canada. As Shaseevan recounted with a smile, “We had been working closely with Natkeeran for years before we even saw his photograph. That’s the level of trust that binds us-and allows us to achieve the impossible.” Back in Sri Lanka, a committed team of local staff and volunteers manage Noolaham’s daily operations-scanning documents, cataloguing entries, maintaining the archive, and overseeing outreach efforts. It is this seamless synergy between global contributors and on the-ground personnel that has made Noolaham not just sustainable, but remarkably scalable.

Impact on Scholarship and Cultural Continuity

Over the years, Noolaham has evolved from a modest digital initiative into a cornerstone of academic research and cultural preservation, according to a senior lecturer at the University of Jaffna, speaking to Jaffna Monitor. “It has transformed how Sri Lankan Tamil history is accessed, interpreted, and archived,” he noted.

“For historians, linguists, and social scientists studying the Tamil community in Sri Lanka, Noolaham offers access to a wealth of primary sources that were once nearly impossible to locate"

“This level of archival access is rare,” the lecturer emphasized. “Students of Tamil literature can now access out-of-print novels and poetry that even major university libraries lack. Scholars researching the civil war or diaspora politics can construct entire narratives using sources that were previously fragmented or forgotten.” With citations to Noolaham now appearing in peer-reviewed books and academic journals across the globe, the platform’s scholarly credibility is firmly established.

Noolaham’s influence has also subtly permeated Tamil political discourse. During a recent online clash between ITAK and TNPF, screenshots of decades-old newspaper clippings and magazine articles-sourced from Noolaham-were exchanged on social media to highlight ideological inconsistencies. Australian-based writer Theivigan Panchalingam captured the irony with dry wit: “Noolaham now supplies the weapons for our political wars.”

The archive’s breadth makes it equally valuable for interdisciplinary research. Its holdings extend beyond literary texts to include social science monographs, statistical records, legal documents, oral histories, and manuscripts on indigenous medicine. Anthropologists, economists, and legal scholars alike have turned to Noolaham as a vital resource. Its dedicated Dalit and Up Country Archives offer crucial insight into historically marginalized communities, while curated collections on Muslim heritage, women’s movements, and regional folklore reflect the archive’s growing commitment to inclusivity.

A Digital Triumph Against the Odds

Comparisons may be drawn to global initiatives like the Internet Archive or the Digital Library of India, but within its niche, Noolaham stands out. As of 2025, the platform hosts more than 173,000 documents encompassing over six million pages-arguably the most comprehensive digital archive maintained by any minority ethnolinguistic community in South Asia. Built on a foundation of volunteer labor, community contributions, and post-war resilience, Noolaham has succeeded where even well-funded state or academic institutions have sometimes faltered. “Archiving has traditionally been the responsibility of governments,” a longtime Noolaham volunteer told Jaffna Monitor. “We are doing the work of a government,” he explained. The platform’s success has begun to inspire other communities around the world. One foreign user-himself a Tamil language learner

Inside Noolaham’s Scanning Lab

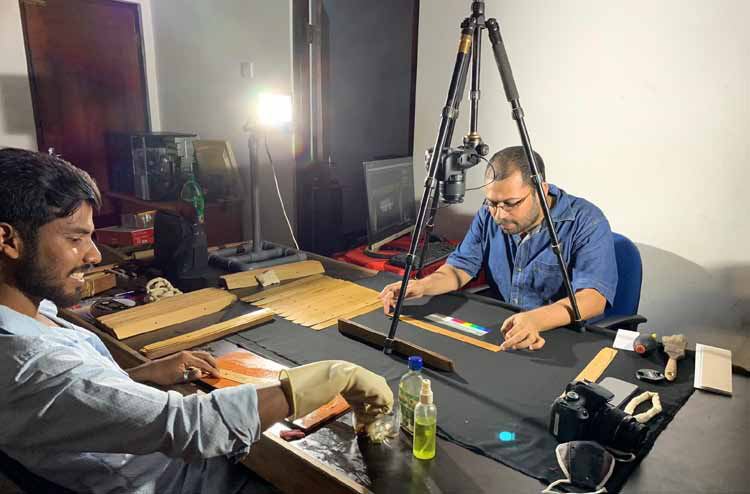

The early documents were typed manually in basic .htm formats. “One person would read aloud while another typed,” Kopinath recalls. “It was slow and painstaking-so much so that in our first year, we managed to digitize only about a hundred books.” But as technology advanced, so did their methods. By the end of 2006, scanning technology had been introduced, dramatically speeding up the digitization process and improving fidelity to the original texts.

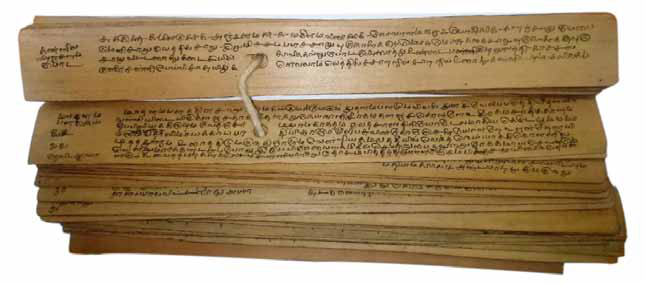

Today, Noolaham employs three distinct scanning techniques, each tailored to the type of material being digitized. Flatbed scanners are used for rare and fragile books, with pages scanned individually. Sheet-fed scanners handle more common titles, where pages can be gently unbound and scanned in batches. But for the most delicate items-such as ola leaf manuscripts-a more sensitive approach is essential.

“Ola leaves are extremely fragile-you can’t feed them into a scanner,” explains Kopinath. “To preserve them, we use a specialized method involving DSLR cameras and controlled lighting. It’s the same process followed by the British Library.”

“When scanning books, we follow international standards,” he adds. “Some people might think it’s enough to snap photos with a phone-but that’s not how we operate. We aim to meet the same documentation standards used by institutions like the British Library.”

“Of course, we don’t have their advanced equipment,” he acknowledges, “but we ensure our methods align as closely as possible with theirs,” he told Jaffna Monitor. praised Noolaham as “a rare example of how a people can digitally reconstruct their cultural identity when their physical heritage has been under assault.” It demonstrates that even in the face of violence, displacement, and neglect, digital tools can become powerful instruments of preservation and resistance.

No Censorship, No Bias: Noolaham’s Commitment to Archival Integrity

“Though each of us may have our own political leanings, we never censor or show bias in what we archive,” said Shaseevan. “We document whatever is available-without prejudice. If someone were to publish a book tomorrow calling Noolaham a den of thieves, and they gave us permission to digitize it, we would archive that too.”

Kopinath echoed the sentiment, recalling a defining moment in Noolaham’s early journey: the decision to archive Murinthapanai (The Broken Palmyra)-a book that sharply critiqued Tamil militant movements. “That was our 1001st archived item,” he noted. “It was our way of saying that this project is committed to preserving all perspectives, not just the convenient or popular ones.”

The decision was not without controversy. “Some of our major donors-who were instrumental in Noolaham’s early growth questioned us,” he said. “They asked, ‘Why would you archive The Broken Palmyra? Isn’t it anti-Tamil?’ Our answer was simple: Whether it’s anti-Tamil or not is irrelevant. It’s a book. It exists. It deserves to be documented.” That principled stance, he explained, gradually earned the trust of the broader community. “Over time, people came to understand that we’re here to document history-not to rewrite it. And that understanding brought even more support to the initiative.”

Safeguarding the Future: Noolaham’s Next Chapter

As Noolaham moves into its third decade, the challenges ahead are as real as the achievements behind. Scaling digital infrastructure, ensuring sustainable funding, training new volunteers, and adapting to rapidly evolving technologies are all part of the road ahead.

“As long as there are Tamil people who cherish their heritage, the spark that ignited Noolaham will continue to burn bright as an eternal flame of knowledge,” one core team member told Jaffna Monitor.

When asked what could significantly improve Noolaham’s capacity, one of its founders, Kopinath, explained: “What we need most is land and a permanent building. Right now, we’re operating out of rented houses on a temporary basis. We’ve been entrusted with thousands of rare books and manuscripts, but we don’t have a secure space to store and preserve them.”

He added, “Our people often donate land to temples and religious institutions. If someone could offer us just a small plot, we could raise the funds ourselves to build the facility we need. At the moment, our office is crammed with shelves and overflowing cabinets. We don’t even have enough space to carry out daily work efficiently. A dedicated space would change everything-it would unlock new possibilities for conservation, training, and outreach.”

The appeal is modest. The vision is far reaching. The question now is-will our society listen?