Alfred Duraiappah was killed 50 years ago, on 27 July 1975, by my early friend—who would later become the LTTE supremo—Prabhakaran, along with a few other young men. Although I had no role in the killing, at the time I felt a deep sense of satisfaction, believing that a “traitor” had been removed and that, for the liberation of our people, such individuals had to be eliminated.

After the murder, Prabhakaran came to my village, Punnalaikadduvan, and I sheltered him for almost a year in my grandmother’s house—a fact I have detailed in my series of interviews with Jaffna Monitor.

Yet, looking back half a century later, I see that it neither made sense nor brought any real benefit to the Tamil people.

The political murder of Alfred Duraiappah

The political murder of Alfred Duraiappah in 1975 was widely seen as the start of the elimination of “traitors” within Tamil nationalist discourse.

Viewed as a major obstacle to Tamil nationalism in the 1970s, he chose cooperation with the Sri Lankan state to secure development for his constituents rather than aligning with Tamil nationalists.

Initially contesting parliamentary and mayoral elections as an independent, Duraiappah served as MP for Jaffna from 1960 to 1965. He joined the Sri Lanka Freedom Party in 1971 and in the 1970 parliamentary election was one of the main contenders in a three-way race with the Federal Party’s C. X. Martyn, who won, and the Tamil Congress. He was elected Mayor of Jaffna in 1970 and served until his assassination in 1975.

His democratic approach focused on electoral victories and securing government funds for development, including the Jaffna Library, the New Market, and other projects. However, to those inspired by Tamil nationalist ideology—especially the LTTE—Duraiappah was seen as a "traitor" to the Tamil cause. His assassination was therefore framed as a heroic act.

I do not wish to engage with these two opposing views but aim to explore the historical and rhetorical construction of the term “traitor” in Tamil nationalist politics.

The Term “Traitor”

The term "traitor" is not unique to Tamil nationalist politics. It is an ancient term present in most languages. Its meaning is not fixed; rather, it is a dynamic construct shaped by specific socio-political and historical contexts. Sharika Thiranagama and Tobias Kelly, in their book Traitors: Suspicion, Intimacy, and the Ethics of State-Building, note that:

“Perhaps most importantly, traitors arguably attract a particular aversion because they are not distant ‘others’ but enemies within.”

Treason involves a violation of loyalty to established norms, values, or political allegiances. The meaning of “traitor” is therefore socially and politically constructed by both state and non-state actors within a specific political context.

"Traitor" in Tamil Nationalist Discourse

In Tamil nationalist rhetoric, the term “traitor” is actualized through public denunciations and political actions, eventually becoming normalized and embedded in discourse. Traitors are granted no sympathy; their elimination is framed as a necessity to preserve the purity of the nation.

Their annihilation is portrayed as a form of societal cleansing.

The official Tamil nationalist narrative posits that anyone collaborating with the Sri Lankan state is a traitor to the Tamil cause. Following independence, Sri Lanka’s state-building project marginalized ethnic minorities, leading Tamil nationalism to emerge as the dominant political ideology in the north and east.

Although Tamil nationalism—originating with the Federal Party in 1949—initially propagated the idea of a “Tamil-speaking people,” promoting an inclusive political agenda that encompassed Muslims and Indian Tamils (Malayaga Tamils), this inclusivity shifted after the 1976 proclamation of Tamil Eelam and the assertion of traditional Tamil homelands. Ethnic nationalism then became the dominant discourse.

While Tamil militancy and the Tamil Suyaadchchi Kazahagam (Tamil Self Rule Party) had already begun advocating for Tamil nationhood from 1970, the Federal Party and later the TULF alliance declared the goal of Tamil Eelam in 1976—partly as a concession to the growing militant movement and partly as a political statement directed at the Sri Lankan state.

Initially, the Federal Party (FP) pursued federalist demands within a united Sri Lanka. Their motto was the protection of "Tamil-speaking people" rather than emphasizing Tamils as a distinct race. Until 1970, the term "traitor" was not part of the FP’s vocabulary. The party engaged in bargaining with the government and, when demands were unmet, resorted to non-violent protest and Satyagraha. For instance, in 1965, the FP conditionally supported the UNP, and M. Thiruchelvam became a minister. Thus, the notion of a “traitor” was not yet associated with political opposition to Tamil Eelam or with elimination.

The 1970s: Shifts in Rhetoric and Action

In May 1970, the SLFP, Communist Party, and LSSP formed the United Front (UF) and won the parliamentary elections. The Federal Party (FP) won 13 seats and the Tamil Congress three. While the UF promoted self-sufficiency and republicanism, Sinhala majoritarianism prevailed, prompting the FP to withdraw from the Constituent Assembly when its demand for federalism was rejected.

In 1972, the Tamil United Front (TUF) was formed after the government rejected its six-point memorandum. Chelvanayagam resigned from Parliament in protest, fuelling calls for a separate Tamil state. Growing impatience among Tamil nationalist youth, mainly from Jaffna district, combined with the state’s failure to address minority grievances, led to the formation of the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) in May 1976, which officially declared the demand for Tamil Eelam.

Simultaneously, the Tamil Student Assembly (Tamil Maanavar Peravai), led by Sathyaseelan, organized protests against the 1970 “standardization” policy, which gave Sinhala students an advantage in university admissions. Although the youth wings of the Federal Party (FP) and later the Tamil United Front (TUF) supported these protests, the TUF did not openly endorse Tamil militancy in its early phase. The government later modified the policy, and standardization, together with district quotas, did benefit Tamil students from underdeveloped areas such as the Vanni and the Eastern Province—but this was largely ignored by Jaffna-based nationalists. Disillusioned Tamil nationalist youth in Jaffna increasingly turned toward militancy, targeting perceived collaborators as enemies of liberation.

Sivakumaran, one of the pioneers of Tamil militancy, exemplified this shift. In July 1970, he planted a bomb under Minister Somaweera Chandrasiri’s car because the minister had spoken of the cultural closeness between Tamils and Sinhalese. Ethnic nationalism was becoming increasingly rigid on both sides, demanding purity and exclusivity. While Chandrasiri was a Sinhalese minister and not a “traitor” in the strict sense, this incident marked the early stage of militancy and the intolerance toward any suggestion of cultural affinity between Tamils and Sinhalese.

The Targeting of Duraiappah

Duraiappah was first targeted in February 1971 by Sivakumaran, when a bomb was planted under his parked car near Vembadi Girls' College. He survived only because of a delay in reaching his car.

Meanwhile, FP members such as C. X. Martyn and Tamil Congress members C. Arulampalam and A. Thiyagarajah — who had been elected under the FP banner (later TUF) — decided to support the new 1972 Republican Constitution and crossed over to the government. These individuals were branded as traitors, and the Tamil Student Assembly (TSA – Tamil Maanavar Peravai) attempted to assassinate Thiyagarajah at his residence in Bambalapitiya, Colombo. He escaped unhurt when bullets struck the wall. The TUF at that time did not condone violence, and in TUF parlance, the term “traitor” remained a political label rather than a call for annihilation.

The 1972 Constitution and Its Aftermath

The 1972 constitution fundamentally altered Sri Lanka's political landscape by elevating Buddhism to the "foremost place," making Sinhala the sole official language (while Tamil remained subject to the limited provisions of the 1958 Tamil Language Act), and removing the minority protections that had been enshrined in the 1946 constitution. Despite the government's economic reforms and nationalizations, minority grievances were systematically ignored, leading to stronger nationalist mobilization in the North.

The TUF responded with organized resistance, launching fasting campaigns, organizing protest rallies, and hoisting black flags to mourn what they saw as a discriminatory constitution. Yet the political reality was more complex than simple Tamil-Sinhala polarization. Tamil farmers in the North actually benefited from the government's import-substitution policies and remained somewhat sympathetic to the United Front (UF).

This was evident when Sirimavo Bandaranaike visited Jaffna in 1974 and drew a huge crowd to her meeting. However, the colonial framing of races—and its continuity, rather than rupture, in postcolonial nation-state building—resulted in a majority–minority discourse that dominated the politics of Sri Lanka.

Internal Contradictions Within Tamil Politics

Caste divisions presented another complicating factor that Tamil nationalist parties struggled to address. The North retained deeply entrenched caste-based discrimination, and the most sustained struggles against it were led by the Communist Party (Peking Wing) in the 1960s. In the 1970 elections, V. Ponnambalam of the Communist Party (Moscow Wing) ran against the legendary S. J. V. Chelvanayagam and came second, drawing significant support from the depressed castes and the working class.

Neither the FP nor the later TUF actively engaged with the caste struggle or adopted a broader social justice outlook. They called for Tamil unity without addressing the fundamental inequalities of caste, class, and gender that divided Tamil society. This narrow approach had geographical limitations as well: despite the FP's dominance in the North, it struggled to gain traction in the Eastern Province, where many Tamils continued to support southern political parties. The notion that all Tamils automatically supported the Tamil nationalist cause was, therefore, more illusion than reality.

Organizational Weaknesses and Ideological Divisions

The TUF's limitations extended beyond social issues to basic political strategy. They failed to launch a sustained civil disobedience campaign, build an effective party network, or forge meaningful alliances with progressive southern forces. Their inability to unite Muslims and Malaiyaha Tamils under the broader "Tamil-speaking people" banner further weakened their claim to represent all Tamil interests.

Meanwhile, alternative Tamil political visions emerged that would prove influential for future militants. V. Navaratnam, who left the FP in 1968, founded the Self-Rule Party, advocating Tamil self-determination combined with racial exclusivity. He asserted that Muslims, despite being Tamil-speaking, were not part of the Tamil race. An admirer of Jewish statehood, Navaratnam translated the novel Exodus into Tamil, which was serialized in the newspaper Viduthalai. His ideology would later influence Tamil militants, including Prabhakaran.

The Politics of Blame

Faced with these organizational weaknesses and lacking a coherent political vision, the TUF leadership found themselves caught between rising militant pressure and diminishing political options. Their fear of losing legitimacy as representatives of the Tamils led them to take the easier route of portraying "traitors" as the primary cause of Tamil disunity.

The Rise of the Annihilation Doctrine

From the 1970s onward, Tamil militants developed a lethal doctrine of "annihilating traitors"—a concept that would fundamentally transform Tamil politics. Rather than denouncing this extremist ideology, the FP and later the TUF chose a path of complicit silence. Their continued use of the "traitor" label in political meetings to describe those who cooperated with the Sri Lankan government made them active participants in creating the atmosphere for political murder.

The Fusion of Language and Violence

The transformation was both subtle and profound. After 1970, the concepts of "traitor" and "annihilation" became fused in Tamil nationalist discourse in ways that had been absent from the FP's earlier vocabulary.

As Tamil militants grew increasingly dissatisfied with the TUF leadership's moderate approach and lack of commitment, they embraced armed struggle as the only viable path forward. In this militant worldview, the annihilation of traitors was not merely justified—it was essential. The TUF's strategic silence served their interests perfectly, allowing them to maintain plausible deniability while benefiting from the climate of fear that militant rhetoric created.

The Poetry of Extremism

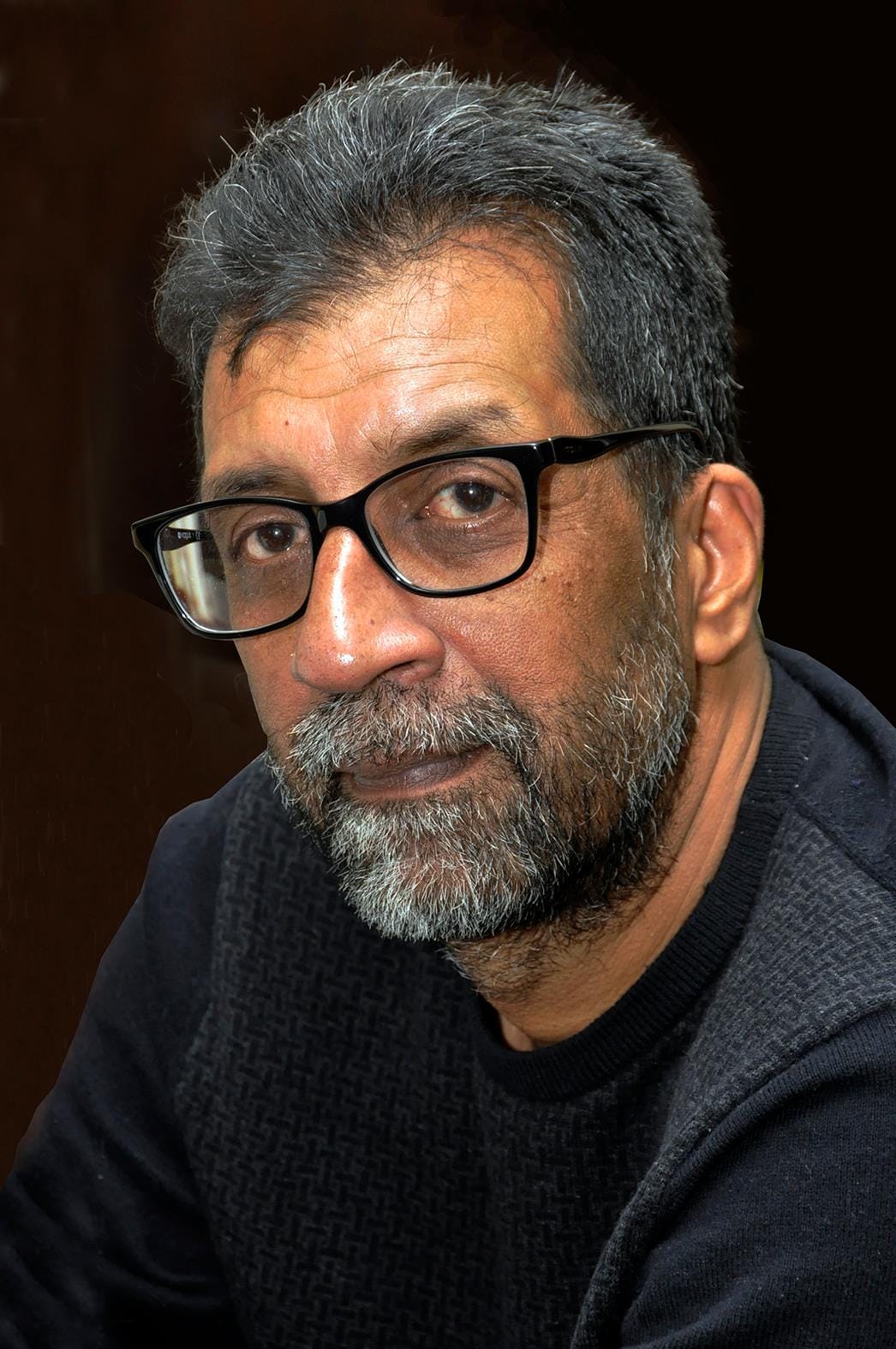

Kasi Ananthan with LTTE supremo Velupillai Prabhakaran

The toxic nature of this discourse found its most chilling expression in cultural production. Party publications, along with influential figures such as Kasi Anandan, actively promoted this rhetoric of elimination. Anandan's poem stands as a particularly stark example of how deeply this ideology had penetrated Tamil nationalist thought:

Come, let us rise—

Weeding out the traitors!

Tamils who betray fellow Tamils,

Know this: our rise begins with severing their heads...

Even if it is our own mother… our own father...

If they find joy in friendship with our foes…

Then strike them down without mercy!

This verse reveals the absolute extremism that the traitor discourse had reached—literally justifying the murder of one's own parents if they were deemed insufficiently loyal to the nationalist cause. The language of "weeding out" reduces human beings to unwanted plants to be eliminated, while the call to "sever heads" strips away any pretense of political civility.

The Tamil Conference Tragedy and Its Exploitation

The January 1974 Fourth International Tamil Research Conference in Jaffna provided a tragic catalyst that militants would exploit to justify their emerging doctrine of violence. The final public event on 10 January drew a massive crowd to what should have been a celebration of Tamil scholarship and culture. Although organizers had reached a verbal agreement with police for the event, the presence of Janardanan—a Tamil Nadu activist who was not part of the official delegation—created unexpected complications.

When police arrived without warning and attacked the crowd, chaos erupted. In the ensuing panic, live ammunition was fired, an electric cable was struck, and nine innocent people died from electrocution. The police violence was both preventable and devastating—a moment that legitimized the assassination of traitors.

Scapegoating and the Erosion of Democratic Legitimacy

Despite the complete absence of evidence that Duraiappah was involved in or supported the police action, Tamil nationalists—including the TUF leadership—blamed him for the police violence. This scapegoating represented a crucial turning point: a democratically elected leader with a clear mandate from his constituents was being held responsible for actions he neither ordered nor endorsed, simply because he was a threat to Tamil nationalist politics.

The Assassination of Duraiappah

After the Tamil Research Conference tragedy, Alfred Duraiappah became a top target for Tamil nationalist militants. Several youths plotted his assassination. Among them, Sivakumaran attempted to finance his group by robbing a bank in Kopay but was caught. On 4 June 1974, he committed suicide when apprehended by the police.

His public funeral, attended by Tamil nationalist politicians, marked a turning point. The presence of these politicians—and their speeches—signified a shift. While the TUF leadership maintained that their political path was non-violence, they expressed respect for the commitment of Sivakumaran and other militants. They argued that although they did not endorse armed struggle, the youth were fighting for the same cause and therefore deserved recognition. Citing Bhagat Singh, they noted that even though the Indian National Congress promoted non-violent resistance to the British, it remained sympathetic to the armed struggle.

On 27 July 1975, Prabhakaran and three others assassinated Duraiappah at the Ponnalai Varadaraja Perumal Temple. Though Christian, Duraiappah had faith in the Hindu deity Perumal. At the time, the LTTE had not yet been formed; the group was then known as the Tamil New Tigers (TNT) and was largely unknown to the public. The LTTE would be formally established on 5 May 1976.

The Institutionalization of Political Murder

The concept of annihilating “traitors” cannot be attributed solely to Prabhakaran or the LTTE. It was a broader ideology within Tamil nationalism from the 1970s, propagated by militants and enabled by the political class. In 1981, PLOTE assassinated former MP Thiyagarajah. Several SLFP organizers in the North were killed not only by the LTTE but also by other militant groups such as TELO.

After 1983, Prabhakaran and the LTTE declared themselves the sole representatives of the Tamil people, branding any opposition as treachery.

“Opposition” and “traitor” became synonymous. In this process, Prabhakaran consolidated his position as supreme leader, and the annihilation of those opposing his ideology became normalized.

By 1986, the LTTE had emerged as the dominant military force. Tamil political parties and rival militant groups were banned and similarly labeled as traitors. Most were dissolved, with their leaders and cadres assassinated. Intellectuals who dared to challenge the LTTE’s ideology were also targeted and killed. The rhetoric of “traitor annihilation” had by then deeply permeated Tamil political culture.

In the pro-LTTE English-language web publication TamilNet, Sivaram, alias Taraki, often depicted assassinated individuals as paramilitary agents working with the state—thereby justifying their elimination. In this narrative, eliminating paramilitaries was synonymous with eliminating traitors.

The Enduring Legacy of a Toxic Ideology

After the LTTE's military defeat in May 2009, the practice of physically annihilating traitors finally ceased. However, the ideological foundation that enabled such violence continues to haunt the Tamil nationalist mindset. Even today, those who dare to criticize the LTTE or question aspects of Tamil nationalist orthodoxy are routinely branded as traitors, demonstrating how deeply this toxic discourse has penetrated Tamil political culture.

Ironically, the traitor-labeling mechanism has now turned inward. Divisions have emerged within LTTE sympathizers themselves, particularly in the diaspora, with competing factions accusing each other of betrayal.

The TULF's Pyrrhic Victory

While there is no concrete evidence that the TULF leadership directly ordered Duraiappah's assassination, their culpability lies in the discursive formation they helped construct. Their persistent use of "traitor" rhetoric provided the ideological ammunition that militants would later use to justify murder. The bitter irony is that the LTTE eventually turned this same weapon against TULF: moderate TULF leaders such as A. Amirthalingam and Neelan Thiruchelvam were themselves assassinated, branded as traitors for their willingness to seek negotiated solutions.

The TULF's construction of traitors, combined with early Tamil militancy's notion of eliminating traitors, gave birth to the LTTE's systematic doctrine of annihilating anyone who opposed or criticized its ideology. The political class that had sown the wind would eventually reap the whirlwind.

The Poetry of Self-Destruction

The ultimate futility and viciousness of the traitor discourse finds its most powerful expression in a Tamil poem by Sivasegaram, which captures the endless cycle of violence that this ideology unleashed:

"Once upon a time, a person was shot and condemned as a traitor.

Then, the one who shot him was shot.

The one who witnessed the shooting was shot.

The one who ordered the shooting was shot.

The one who accused him, and the one who prosecuted him, were shot.

The one who testified, and the one who delivered the verdict, were shot.

The one who accepted the verdict was shot, and so was the one who opposed it.

Even the one who did nothing was shot as well".

"துரோகி எனத் தீர்த்து முன்னொரு நாள் சுட்டவெடி

சுட்டவனைச் சுட்டது

சுடக்கண்டவனை சுட்டது

சுடுமாறு ஆணையிட்டவனைச் சுட்டது

குற்றம் சாட்டியவனை வழக்குரைத்தவனைச்

சாட்சி சொன்னவனைத் தீர்ப்பு வழங்கியவனைச் சுட்டது

தீர்ப்பை ஏற்றவனைச் சுட்டது எதிர்த்தவனைச் சுட்டது

சும்மா இருந்தவனையும் சுட்டது"

A Personal Reckoning

I write this analysis not as a distant observer, but as someone who was once deeply embedded in this very ideology. I was inspired by Tamil nationalist thought from 1972, while still a student, and I too subscribed to the "annihilation of traitors" discourse. I had known Prabhakaran since 1974, and after Duraiappah's assassination, I provided shelter to both Prabhakaran and Patkunam—a member of Duraiappah’s assassination team, later killed by Prabhakaran himself—at my grandmother's house. I became part of the TNT network and was among the founding members of the LTTE in 1976.

It was only after leaving the LTTE in April 1984 that I began to question the ethnic nationalist ideology and recognize its fundamentally destructive nature. This personal journey from true believer to critic has taught me that the capacity for self-reflection and change exists even within the most rigid ideological frameworks—but only if we have the courage to confront uncomfortable truths about our past.

The Path Forward

To conclude, the Tamil polity must engage in critical reflection on the dangerous and toxic “traitor” discourse that remains embedded within Tamil nationalist ideology. “Traitor” is inseparable from ethnic nationalist discourse. Ethnic nationalism is a byproduct of colonialism. We need to decolonize the colonial mindset.

In Neither Settler nor Native, Mahmood Mamdani points out that “the task is to reimagine political community without colonial categories and reform polities on this basis.” He emphasizes that “such violence needs to be understood as political rather than merely criminal.” Therefore, the task is to question the dominant political discourse and to reimagine politics without invoking concepts such as the traditional homeland, borders, unique culture, and identity. As Mamdani states, “nationhood is instrumentalizing culture for domination… we can only have democracy without the nation-state.” This insight is equally applicable to Sinhala Buddhist nation-state building, which is also based on exclusivity. When we stop thinking within an ethnic nationalist framework, the idea of “annihilating the traitor” disappears.

The murder of Alfred Duraiappah should be revisited not through the lens of an ethnic nationalist framework, but through the fundamental principles of humanity, tolerance of criticism, pluralism, and democratic values. Only by honestly confronting this dark chapter can Tamil society hope to build a more inclusive and democratic future.

Note: The author, Chinniah Rajeshkumar—better known as Ragavan—is a co-founder of the LTTE and now serves as a legal advisor and activist.