In 2019, the Tamil literary world witnessed the arrival of a remarkable new voice through Ayya — The Ninety-Five-Year-Old Child! by Vadivarasu, a native of Thiruvadathanur village in Tamil Nadu’s Tiruvannamalai district. Written with disarming intimacy, the book traces how an ageing father — a hardworking farmer, an unlettered yet extraordinary man who served as the village pūchāri (priest), performed therukoothu (Tamil folk street theatre), and even acted as the de facto veterinarian for every cow, goat, and sheep in Thiruvadathanur — quietly shaped his son’s emotional and intellectual universe through lived values, everyday acts, and the unspoken pedagogy of example.

The book’s success was immediate and widespread, travelling across a vast and diverse readership. In the six years since, Vadivarasu has produced nearly twenty works — fiction, non-fiction, poetry, monologues, and even a lexicon. Each stands apart in form, structure, and intellectual ambition; many of them inaugurate literary modes that Tamil literature had scarcely imagined before.

Remarkably, Vadivurasu is an MSc holder in Computer Science — a qualification that could have secured him a lucrative and comfortable career. Instead, he chose a radically different path: a life of principled minimalism, built on the discipline of living with the bare minimum, dedicating his days entirely to writing, reflection, and creative experimentation.

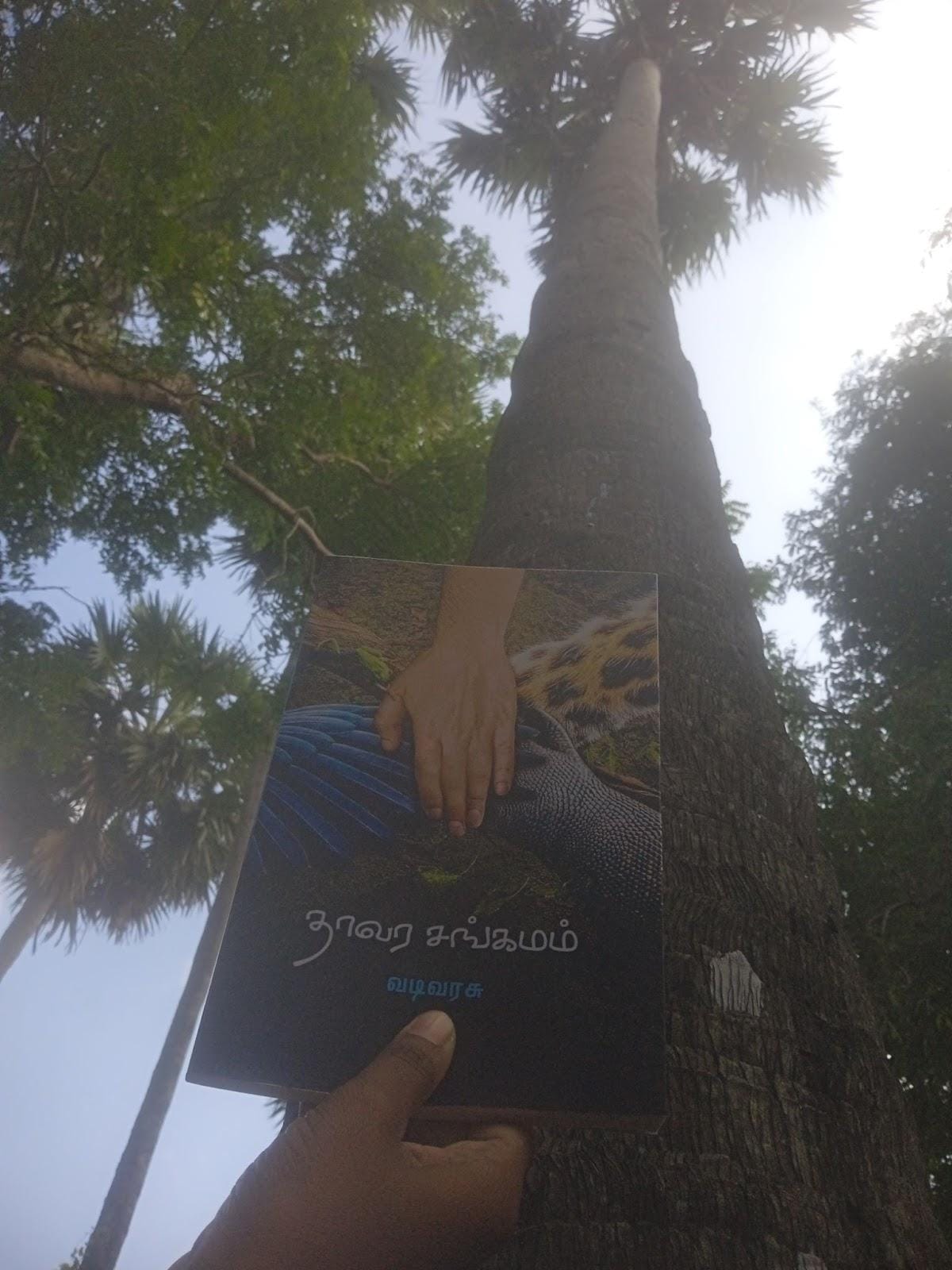

On the 8th of December, he did something that profoundly touched Jaffna’s cultural imagination. He released his newest work, Thaavara Sangamam (“The Confluence of Plants”), beneath the shade of an ancient palmyrah in Navaly — a symbolic, almost poetic tribute to Navaliyoor Somasundara Pulavar, the illustrious author of Thaalavilaasam, who left behind more than four hundred kalivenba verses — a classical Tamil poetic form known for its strict metrical discipline, musical cadence, and elevated literary style — celebrating the majesty, utility, and mythology of the palmyrah.

Later that evening, we met him in Jaffna for an extended, absorbing conversation.

This is Jaffna Monitor’s interview with him.

The title Thaavara Sangamam itself is quite intriguing. Tell us about this book..?

The title comes from a line in the thirtieth verse of the Thiruvachakam:

“செல்லாஅ நின்ற இத் தாவர சங்கமத்துள்” — “In this unmoving–moving confluence that stands still.” That phrase — thaavara sangamam — lingered in my mind, and I chose it as the title.

In modern Tamil, thaavaram simply means “plant.” But in classical Tamil, thaavaram refers to the static category, while sangamam refers to the dynamic category. In other words, the unmoving and the moving; the inert and the animate. Trees, shrubs, climbers, grasses, fungi, mushrooms, seaweeds and the like belong to thaavaram — the unmoving world. Aquatic creatures, reptiles, birds, animals, humans, and even divine beings belong to sangamam — the moving world.

For thaavaram, the equivalent terms include: the unmoving, the anchored, the standing, the rooted, and so on. For sangamam, the equivalents include: the moving, the collective, the gathering, the assemblage, the animate.

Classical Tamil assigns eight conceptual meanings to thaavaram: the static category, home, immovable objects, wooden structure, foundation, place, body, and lingam.

Sangamam carries seven conceptual meanings: confluence, the meeting of two rivers or of a river with the sea, the sacred congregation of Shiva’s devotees, planetary conjunction, union, the animate category, and sangama wealth.

Whenever I reflect on this title, it still fills me with wonder. Why should this phrase — familiar to millions through Sivapuranam, inscribed in almost every Shiva temple in Tamil Nadu — reveal itself to me with such distinct clarity? Why should I, of all people, feel compelled to write an entire book under its inspiration? That, I believe, is the subtle mystery of creation.

After my earlier work on the static category, this was the book that demanded the most labour. It explores a wide range of thaavara–sangamam encounters: tree, shrub, climber, ant, seashell, conch, tortoise, dog, elephant, human, divine being — and many more. The book has received warm appreciation from readers known and unknown to me.

Why did you choose Navaly, Jaffna, as the place to release this book?

Navaliyoor Somasundara Pulavar, who was born in Navaly, is a scholar I deeply revere. In this book, I have written extensively about his celebrated work Thaalavilaasam, a text devoted entirely to the palmyrah tree.

In Thaalavilaasam, the palmyrah is even compared to a young girl:

“பெண்பிளையுந் தண்பனையும் பேணிவளர்த் தால்வருடம்

பண்பிலொரு பத்திற் பயன்கொடுக்கும்…”

(Loosely translated: Just as a girl raised with care grows in grace, the palmyrah too, when nurtured, yields tenfold benefits.)

Thaalam means palmyrah; vilāsam means address or abode — as in Arichandra Vilasam or Dambachari Vilasam. Thus, Thaalavilaasam literally means “the address of the palmyrah.”

From root to crown, Navaliyoor Somasundara Pulavar describes — in exquisite verse — every useful part of the palmyrah: when each part can be harvested, how it must be processed, what objects can be made from it, and the benefits it bestows on people. This entire work, composed in the kalivenba metre, contains over four hundred verses that reveal to the Tamil world the majesty, utility, and cultural depth of the palmyrah.

The text abounds in rich metaphors and rare, beautiful Tamil words related to the tree. Published in 1940 by the Tholpuram Palmyrah Industry Development Union, it lists 801 distinct uses of the palmyrah tree.

Let me offer just two examples Pulavar gives:

To show that the palmyrah lives long and continues to be useful — and that even when felled, it still serves as strong timber — he writes:

“நட்டாய் இருவருட நானிலத்திற் காய்த்துநிற்கும்

பட்டாய் இருவருடம் பாழ்போகா”

(Loosely translated: Planted, it flourishes for generations in all directions;

felled, it still stands firm for years without decay.)

To express that if a palmyrah seed manages to sprout — escaping goats, cattle, and grazing animals — it will be unfailingly fruitful, like the truthful words of ancient sages, he writes:

“முப்பாசந் தீர்த்த முனிவர்மொழி வாய்மையோ

லெப்போதுநின்று பயனீயுமே”

(Loosely translated: Like the words of sages purified of all three impurities,

It remains eternally true and yields its benefits unfailingly.)

Someone may ask: A whole book on a single tree? And entirely in verse?

Yes. If a poet was inspired to compose such a work, it shows how immense — how extraordinary — the greatness of the palmyrah must have been, and still is.

That is why I felt not only the desire to write about Navaliyoor Somasundara Pulavar, but the urge to release my own book in his birthplace — beneath a palmyrah tree he might once have seen, under the very shade that shaped his imagination. I travelled to Navaly for that reason, and released my book there.

In your view, in what ways does Navaliyoor Somasundara Pulavar hold significance within the Tamil literary world?

In the Tamil literary tradition, many poets have sung of kings, warriors, patrons, and the great affairs of their time. But Somasundara Pulavar stands apart. He did not confine his vision to courtly praise or human endeavours; instead, he turned his poetic gaze towards the palmyrah tree.

To compose an entire book, meticulously and magnificently, about a single tree — and to extol it with the same dignity and grandeur usually reserved for royalty — is an act of genius, devotion, and deep ecological wisdom. It reveals a poet who recognised divinity not only in temples and coronations, but also in the quiet forms of life that stand beside us every day.

For me, such a poet towers above many others. He deserves to be honoured, remembered, and celebrated. That is why I travelled to the soil of his birth and released my book there — as a personal offering, a salute to a master whose imagination could elevate a tree to the status of a king.

And to ensure that his legacy continues to breathe among the people, I placed the book in the renowned Jaffna Public Library — so that readers here may encounter his brilliance, rediscover the grandeur of the palmyrah, and keep his imperishable name alive.

In what ways do you feel Thaavara Sangamam carries particular significance?

In this book, the divine Mother Kanchi Kamakshi — the supreme embodiment of grace and virtue — is one and the same as the tiny ant that shares our world as a rain-harbinger. The thorn-laden pūlā tree, revered as the sacred temple tree, is no different from the great banyan that sprouted at the very spot where the woman Thimmamma ascended the pyre.

The palmyrah that has lived beside us for three thousand years is one and the same as the sea turtle struggling at the edge of extinction.

In essence, the book rests on a single conviction: to speak of the inherent worth of all living beings, to nurture a deeper and nobler relationship with them, and to affirm that the world must survive — and can survive — only when we honour every form of life.

That, in truth, is why I wrote this book.

You have been in Sri Lanka for the past three weeks. How has this journey been for you?

It has been a deeply fulfilling journey. The first reason is very personal: this is the first international trip for my son, ஐ (Ai), and my wife, Mathi. And their first journey happened to be from our motherland to what I lovingly call our sister-land — Sri Lanka.

The second reason is the profound historical significance of the places I visited. I had the chance to see Jaffna, Mullivaikkal, Trincomalee and several other important sites with my own eyes. And I was able to release Thaavara Sangamam exactly in the place my heart longed for.

If not for the severe floods, I would have travelled to many more places. But apart from that one disruption, this has been an unforgettable and deeply rewarding trip.

Tell us about your upcoming travels and your next book.

Beginning January 2026, I plan to climb one mountain every month for five consecutive years — sixty mountains in total. Each mountain will be at least a thousand feet high. The journey will begin in my birthplace, Thiruvannamalai, and extend to Kailash in the Himalayas.

As for my next book, I am about to begin a book titled 'தமிழணங்கே' (“Thamizhanangē..”). It will be entirely about Tamil, Tamils, and Tamil Nadu. If I had to summarise it in a single line, I would say this: an attempt to compress an ocean of Tamil greatness into the size of a palmful. That is all.