If you trace the arc of Tamil political leadership from Independence to today, one pattern repeats with stubborn persistence: our fate has been decided almost exclusively by lawyers. From Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan and G.G. Ponnambalam to Thanthai Chelva and Amirthalingam, and now to Sumanthiran and Gajendrakumar—the legal profession has monopolized Tamil political space for more than a century.

Nothing personal against lawyers. But their craft is built on argument, narrative construction, and the fine art of bending truth in the service of a client. The skills that win courtrooms do not automatically translate into leadership rooted in people’s realities.

By the late 1970s, militant youth — disillusioned by the all-talk, no action political style of chest-thumping lawyers who delivered speeches but no solutions — began calling these legal-politicians “வெள்ளை வேட்டிக் கள்ளர்” — thieves in white veshti.

Briefly, militant actors replaced legal politicians. But after the war’s end in 2009, militants disappeared, and lawyers returned to leadership, as if history had rewound.

Now, as if lawyers weren't enough, we've graduated to judges. Retired judges are being packaged as political messiahs.

The Pensioner’s Disease

Here comes another problem. In our community, retirement is not a phase — it’s a personality crisis. The moment the government stamp fades, brand-new identities are born simply because they cannot sit idle at home.

Apparently, after forty years of government service, sitting quietly at home and listening to one’s wife’s gentle nudgings seems to violate some unwritten code of Tamil male dignity.

One of my relatives has rebranded himself as a political analyst. A retired principal becomes a full-time marriage broker. Another civil servant sells insurance with the passion of a man who has finally discovered his life’s true calling. One becomes a temple trustee; another takes up land brokering. And then you have the ambitious retirees — those who look at Tamil people and think, “These folks are just iḷlichchavāyans,” meaning easy to fool, gullible simpletons — and therefore feel emboldened to launch themselves into politics. The most recent example is former High Court Judge M. Ilancheliyan.

We made the same mistake with C. V. Wigneswaran, a former Supreme Court judge — a decision that led to one of the most humiliating chapters in our political history, from which we have yet to recover.

Our Folly of Trusting Judges Blindly

What makes this transition dangerously easy is our collective delusion: we naïvely believe that anyone who once wore judicial robes must automatically embody honesty and virtue simply because they delivered judgments. We forget a basic truth — judges are appointed to apply the law and deliver justice because that is their job, not because they possess some divine moral purity. There is nothing extraordinary or praiseworthy about doing what the position legally requires.

Ironically, many people still assume that judges are the eternal torchbearers of truth. A Tamil Nadu writer once asked me with a wicked smile: “But weren’t most judges lawyers first? How do you expect someone who spent half his life twisting facts to suddenly become Raja Harishchandra the moment he puts on a robe?”

And let’s not forget — just last week, the Judicial Service Commission removed twenty judicial officers, including a High Court judge, after investigations prompted by public complaints.

So this myth of spotless, halo-wearing judges? Forgive me if I remain skeptical. I rest my case.

C.V. Wigneswaran: A Cautionary Tale in Magical Thinking

After the war’s brutal end, when provincial elections were finally announced after years of delay, Tamil people waited anxiously to see who would lead the Northern Province. It was a historic moment loaded with expectation.

The TNA leadership — especially the late R. Sampanthan — made a decision that has since become a textbook case of political naïveté. Against internal objections, they insisted that Justice C. V. Wigneswaran was the ideal candidate. Sampanthan’s reasoning was embarrassingly simplistic: he is high-profile; therefore, he will shine internationally. The logic went like this — former Supreme Court judge equals honest, wise, diplomatic, politically astute, and capable of “delivering a good verdict for the Tamil people.”

It was magical thinking disguised as strategy.

The TNA then campaigned with almost childlike innocence, selling the fantasy that a man who once wore judicial robes would automatically transform into a saviour.

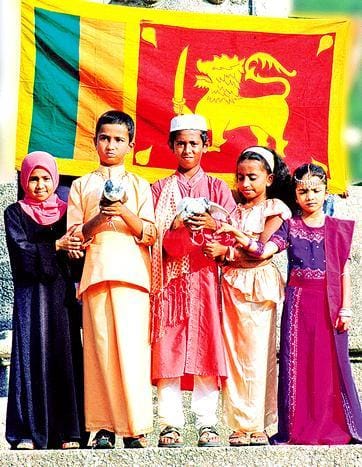

And our people — I mean the decision-making elite of Jaffna — were perfectly comfortable with the choice because he ticked the “respectability boxes”: Saiva Vellālar, no alcohol, non-smoker, English-speaking, respectable job title.

A friend of mine joked: “The TNA searched for a Chief Minister the way Jaffna families search for a groom — caste, habits, job title, English, everything checked. The only thing they forgot to check was his mental stability. That mistake happens in many marriages, too.”

The result was catastrophic.

We ended up with a Chief Minister who became an embarrassment in the political history of Sri Lankan Tamils — a man who left millions of rupees unutilised simply because he was incapable of governing. A man lacking emotional maturity, basic decency, and fundamental self-discipline. He turned the Chief Minister’s office into a circus.

Within weeks of assuming office, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Jaffna. Modi treated him with the full respect accorded to a Chief Minister.

The next day, after Modi returned to India, Wigneswaran wrote a letter — on the official Northern Province Chief Minister’s letterhead — requesting Modi’s intervention to release the “disciples” of his so-called spiritual guru, the notorious godman Premananda, who died in an Indian prison after being convicted of sexually assaulting minors.

Then came another unforgettable incident. India invited him and other Tamil leaders for high-level discussions on political matters. On the morning of this crucial meeting, Wigneswaran simply… disappeared.

After considerable chaos, Indian authorities finally located him at Premananda’s ashram, blissfully detached from reality, while others were waiting to discuss the political future of the Tamil people.

In Jaffna Tamil, we have a word: keela (கீலா) — someone who swings wildly between emotional extremes, crying one minute and laughing the next, utterly lacking inner steadiness.

Today, after many years and numerous blunders, even those who once defended him now openly acknowledge: Wigneswaran was indeed a keela case.

The Deadly Consequences of Treating Politics Like a Post-Retirement Hobby

Politics cannot be treated as a pensioner’s leisure activity. It is not an evening hobby picked up after retirement, nor a gentle pastime like babysitting grandchildren once government service comes to an end. Real politics requires a particular temperament, years of grinding practice, and a brutal kind of experience that no courtroom, classroom, or government office can ever provide.

It tests people daily — often ruthlessly. You cannot stroll into it at sixty, after a full government career, and expect to master its rhythm. Max Weber wrote that “politics is the strong and slow boring of hard boards.” It demands stamina, not nostalgia.

Otto von Bismarck warned that “politics is the art of the possible” — a sentiment forged through decades of battles, alliances, and betrayals. Understanding “the possible” requires living inside the machinery for years: knowing how people think, how institutions behave, how power shifts, and — most critically — how compromise prevents society from disintegrating.

Winston Churchill, who survived wars and countless political near-deaths, put it even more bluntly: “Politics is almost as exciting as war, and quite as dangerous. In war, you can only be killed once, but in politics, many times.”

Yet, retired officials often assume that seniority automatically equates to political wisdom. The truth is harsher: politics is a craft. And like any craft, only those who have spent years shaping it, bending it, and sometimes being broken by it, truly learn to wield it. Expecting a pensioner with zero political experience to excel in politics is as absurd as expecting me — a journalist — to perform heart surgery after retirement.

Which is precisely why treating politics as a post-retirement experiment has failed so spectacularly in our community.

Ilancheliyan’s Calculated Campaign

In Jaffna, this is no secret. Ilancheliyan’s brother — already holding a position in the Tamil Arasu Kachchi’s Islands branch — has been quietly mobilising friends, networks, and well-wishers to fulfil his long-cherished dream of seeing his brother crowned Chief Minister. And Ilancheliyan’s recent tours across diaspora countries have only fertilised that soil.

Those familiar with Jaffna’s political circles know the script: create buzz, inflate the perception of popularity, and pressure the traditional Tamil party — the ITAK — into announcing him as their Chief Ministerial candidate. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, ITAK will refuse; its acting General Secretary, Sumanthiran, is already eyeing the post. Which is why Ilancheliyan and his circle have prepared an alternate route — a coalition of non-ITAK Tamil parties declaring him their consensus candidate. The signs of this happening are already visible.

Whether Tamil parties eventually accept Ilancheliyan or firmly shut the door on him, one truth remains: a section of Tamil society is hungry for such figures. They long for “outsider saviours” to descend and fix the mess.

That expectation is not the flaw. The flaw lies in the failure of the political parties.

For sixteen years after the war, Tamil nationalist politics has failed its simplest duty: producing leaders. Not election-time commentators or social-media philosophers — real leaders with grassroots credibility and ideological clarity. Today, you cannot name even one with genuine mass appeal.

Instead of cultivating such talent, Tamil parties spent years fighting among themselves, issuing unread statements, splitting and re-splitting, and recycling the same tired faces. While they slept, the NPP took seven seats, and even the controversial doctor-turned-politician Archchuna won as an independent.

Now, with only whispers of Provincial Council elections, Tamil politics once again gravitates toward a retired judge — as if no living political talent exists.

This is not a strategy; it is self-indictment. Choosing outsiders is an admission that the parties have produced no one from within. And that failure belongs to leadership, not the people.

Leadership’s core duty is to cultivate talent — to build political thinking, governance skills, discipline, empathy, ideological clarity, communication, and public presence. Earlier Tamil leaders, despite their flaws, understood this. They mentored young activists, challenged them, shaped them — and from that came a generation that was politically literate and intellectually sharp.

Today’s leaders have abandoned this responsibility. Many parties now resemble old houses with leaking roofs — and when it rains, they rush next door to borrow a neighbour’s umbrella.

Diaspora Kingmaking: A Warning Sign

It began with Ilancheliyan’s grand diaspora tour. He went first to London, where he tearfully claimed he had been unfairly denied a last-minute promotion that would have extended his judicial service by four years. Tears rolled down his cheeks — a familiar sight to those who know him. This was not his first public breakdown. He is, quite simply, a man who cries easily. I have witnessed it myself, more than once.

From London, he travelled to France, then Switzerland. At every stop, he received elaborate hero’s welcomes from diaspora communities — especially people from Velanai, his birthplace, and other Jaffna islands, many of whom are now economically powerful abroad. At one London event, an emotional attendee reportedly told him, “I will fall at your feet and beg you — you must be our next Chief Minister to save the leaderless Tamil people.”

Unsurprisingly, Ilancheliyan cried again.

Let us assume he harbours political ambitions. That is his right. But if he truly wishes to enter politics, why did he begin not among the people who actually vote in Sri Lanka, but among diaspora circles thousands of miles away?

The answer is uncomfortable — and exposes a deeper malaise within Tamil political culture: a section of the diaspora believes that because it has money, it also has the authority to dictate leadership, strategy, and destiny to the Tamil people who actually live here. This is not merely misguided; it is profoundly tragic.

A part of the diaspora genuinely seems to think they can decide who should lead Sri Lankan Tamils, who should contest elections, who should be installed as Chief Minister — all while living abroad under different nationalities and entirely different social realities. I have no objection if diaspora members return here, renounce foreign citizenships, and stand for election. That would be honourable.

However, I have serious objections to foreign passport-holders — individuals neither fully committed to the land of their birth nor fully to the nations they have adopted — attempting to engineer political outcomes in Sri Lanka from afar. It is morally dubious, democratically questionable, and frankly nauseating.

Sri Lankan Tamil politics must be shaped by those who live here, suffer here, vote here — not by people who want to orchestrate the show from luxury halls in Paris or meeting rooms in London.

By launching his unofficial election-backing campaign in the diaspora, Ilancheliyan sends a clear message: if he ever becomes Chief Minister of the Northern Province, his loyalties will tilt toward the trouble-making section of the diaspora that wants Sri Lanka kept in perpetual flames, rather than toward the people who actually live here. He risks becoming a proxy for those who thrive on chaos — not a genuine Tamil leader rooted in the struggles of grassroots Tamils.

Retired by Law, Not Wronged by Politics

Let us examine Judge Ilancheliyan’s claim of being “unjustly denied promotion” with clarity rather than sentimentality, because the narrative he carried to London, Paris, and Geneva does not survive even mild scrutiny.

He was not terminated midway, dismissed, or pushed out. He retired on 20 January 2025, exactly as the law required. His grievance is simply that had he been elevated to the Court of Appeal a few days earlier, he could have continued for several more years and avoided what he now calls “forced retirement.” This lament has been repeated at almost every diaspora event.

By his own admission, he did everything possible to postpone his retirement. He wrote multiple appeals to President Anura Kumara Dissanayake. He met the President on 28 November 2024 as President of the High Court Judges’ Association, reminded him of his seniority, posed for photographs, and urged that promotions be fast-tracked before the year-end court vacation. The President listened politely and smiled for the camera. That was the end of it.

When four Court of Appeal judges were elevated to the Supreme Court on 12 January 2025, four vacancies opened — theoretically creating space for him. But the very next day, the President left for China on an official visit. There was no time for the Constitutional Council to meet, deliberate, and formalize appointments before the January 20 deadline. By the time the President returned on the 18th, only two working days remained. Judicial appointments do not materialise overnight simply because one judge wishes to extend his service.

He retired on schedule — not due to conspiracy, but due to the calendar.

What he describes as "injustice" is, in fact, standard judicial practice. Sri Lanka's courts operate under mandatory retirement ages:

- 65 for the Supreme Court

- 63 for the Court of Appeal

- 61 for the High Court

Hundreds of judges have retired exactly in this manner. When considering judicial promotions, the judiciary generally weighs the length of remaining service alongside other factors. Continuity benefits from appointees having sufficient years ahead to serve meaningfully.

The case of Justice M. Mohamed Laffar demonstrates the complexity of these decisions. Although he was the senior-most Court of Appeal judge in early 2025 and was nominated by President Dissanayake to the Supreme Court in June 2025, this nomination became controversial precisely because Laffar was set to retire on June 18, 2025—just two days before the Supreme Court vacancy would arise on June 20. The Constitutional Council's consideration of this appointment highlighted concerns about such short-term elevations.

In the January 2025 Supreme Court appointments, Laffar was not among those selected despite his seniority. Instead, Court of Appeal Judges Sobitha Rajakaruna, Menaka Wijesundera, Sampath B. Abeykoon, and Sampath Wijeratne—all of whom had more years before reaching the Court of Appeal's mandatory retirement age of 63—were appointed.

Immediately after Ilancheliyan reached the High Court retirement age of 60 in January 2025, Court of Appeal vacancies were filled through routine succession. High Court Judges K.M. Sarath Dissanayake and Pradeep Hettiarachchi—both the most senior High Court judges and both with years remaining before reaching age 61—were nominated and sworn in on January 9, 2025. When one judge reaches the age cap, the next eligible candidate with an adequate service horizon typically steps forward.

The January 12, 2025, Supreme Court promotions further illustrate why remaining service matters in judicial appointments. All four newly appointed Supreme Court Justices—Rajakaruna, Wijesundera, Abeykoon, and Wijeratne—have years of service remaining before reaching the Supreme Court retirement age of 65. If Ilancheliyan had been elevated to the Court of Appeal at age 60, he would have served at most three years before reaching retirement age. Similarly, if Laffar had been elevated to the Supreme Court at age 63, his tenure would have been limited to two years.

The logic here is institutional, not personal.

It is, therefore, difficult to accept his claim of “injustice.” What he experienced is exactly what dozens of senior judges before him have experienced. He was not forced to retire — he retired because the law mandated it. His disappointment is understandable, but disappointment is not injustice. Missing out on a late-career promotion is not the collapse of the judicial system. It is simply the normal rhythm of judicial life.

Which brings us to the uncomfortable question: If the facts are this clear and procedural, why has this story been carried across diaspora stages as a tale of betrayal, timing conspiracies, and late-career heartbreak?

Perhaps because diaspora audiences — far removed from the realities of judicial systems — are always hungry for heroes and martyrs. And because, for those seeking a political future, the temptation to convert personal disappointment into a communal grievance is simply too strong to resist.

The Ethics of Judicial Lobbying

Now, a critical question arises—one Ilancheliyan dragged into the public arena himself. He openly admits to seeking elevation, even writing four personal letters to the President requesting promotion. This forces us to pause: if a judge repeatedly appeals to the Head of State for personal advancement, and then receives it, how can that judge later adjudicate cases involving the same President or government with any claim to independence? How would the public trust such verdicts? Would he remain a judge—or become, effectively, another extension of the Executive, much like a presidentially loyal military chief?

Traditionally, judges have maintained a dignified distance from political authority. They do not lobby for positions, negotiate extensions, or weep publicly over promotions that did not materialize. Their moral authority rests on the perception—and reality—of detachment.

Yet here we have a senior High Court judge who not only sought elevation, but did so emotionally, repeatedly, and directly. Can someone who petitions the Executive for career advancement truly claim judicial impartiality?

In most democracies, including Sri Lanka, judicial appointments are made by the President and the Constitutional Council based on seniority, merit, and institutional need. The process is designed precisely to shield the judiciary from personal influence. This is why many observers found it troubling that Ilancheliyan personally petitioned the President through multiple letters and face-to-face appeals. As one legal commentator remarked after hearing the judge's speeches abroad: "No judge who canvasses for promotion can claim to be independent."

In that view, Ilancheliyan's error lies not in failing to get promotion, but in seeking it through political favor in the first place.

If anything, the true irregularity—the true ethical breach—would have been granting a last-minute extension to a judge who personally lobbied for it. That would have been perceived as unfair by colleagues, damaging to institutional culture, and contrary to the principles that safeguard judicial independence.

It’s Time to End the Pensioner Era — and Begin the Age of Real Leaders

Tamil politics stands at a crossroads. We can continue this absurd tradition of importing retired officials, recycling legal elites, and outsourcing leadership to pensioners who treat politics as a late-life hobby — or we can finally demand that our parties do the hard, unglamorous work of building real leaders from within.

Let us be honest: when C. V. Wigneswaran became Chief Minister, he was 74 years old. Judge Illancheliyan, now being marketed as the next saviour, is 63. The Wigneswaran experiment should have cured us of this habit. It clearly did not.

If we refuse to learn now — if we once again allow a retired judge to be crowned without political experience, organisational grounding, or grassroots connection — then we will simply get what we deserve: more disappointment, more dysfunction, and more years wasted while younger, sharper, more connected leaders are pushed aside.

We deserve better than the old culture of white-veshti elites — and the new fashion of black-coated retirees auditioning as saviours. We deserve leaders who rise through sweat and struggle, not through farewell speeches and retirement ceremonies.

The future of Tamil politics will be shaped by one decision: whether we continue outsourcing our destiny to pensioners… or whether we finally choose to build a generation of leaders who will live with the consequences of their own decisions.

The question is no longer rhetorical.

Are we ready to demand a new politics — or do we still prefer the comfort of old mistakes?

கணியன் பூங்குன்றன்

Kaniyan Pungundran

Editor-in-Chief,

Jaffna Monitor