Italy’s recent victory over Nepal — a side widely regarded as far superior in the associate cricketing world — has raised more than a few eyebrows. For many, it was an upset. For those who know the deeper story of Italian cricket, it was something else entirely: a reminder of a forgotten past making itself heard once again.

Cricket was once a visible presence in Italy. One of the country’s oldest sporting institutions, the Genoa Cricket and Football Club, founded in 1893, still carries the name of the game in its title. But history intervened. Under Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime, cricket — seen as irredeemably English — was gradually pushed to the margins. Football was elevated as the sport of nationalist pride, and cricket simply withered. Italy became a football nation. The game all but vanished.

Yet cricket waited for revival.

And when that revival finally came, it arrived not from London or Melbourne, but from an unlikely corner of the cricketing world: Jaffna.

Francis Alphonsus Jayarajah — born in Jaffna and educated at St. Patrick’s College — arrived in Rome on a religious scholarship to study mathematics. What he found was a country that had almost entirely forgotten the game he loved. So he began from scratch.

Often described as the “father of Italian cricket,” Jayarajah did not merely reintroduce the sport — he institutionalised it. He helped establish the Italian Cricket Association in 1980, captained Italy on its first official overseas tour in 1984, and led the national side for a decade until 1994. Under his stewardship, cricket took root once more in Italian soil.

In this exclusive interview with Jaffna Monitor, Francis Alphonsus Jayarajah reflects on exile, identity, perseverance — and the unlikely journey of cricket from Jaffna to Rome.

Sir, some people describe you as the ‘father of Italian cricket.’ Would that be an accurate characterisation?

That is what people say. I arrived in Italy in 1968. From 1968 to around 1980, I was playing cricket informally with groups connected to embassies and religious colleges. At the time, the game was largely sustained by expatriate communities. By around 1980, the number of embassy personnel actively playing had declined. It was then that I met an Italian, Simone Gambino, who encouraged me to introduce the sport more formally to local players. That conversation marked a turning point.

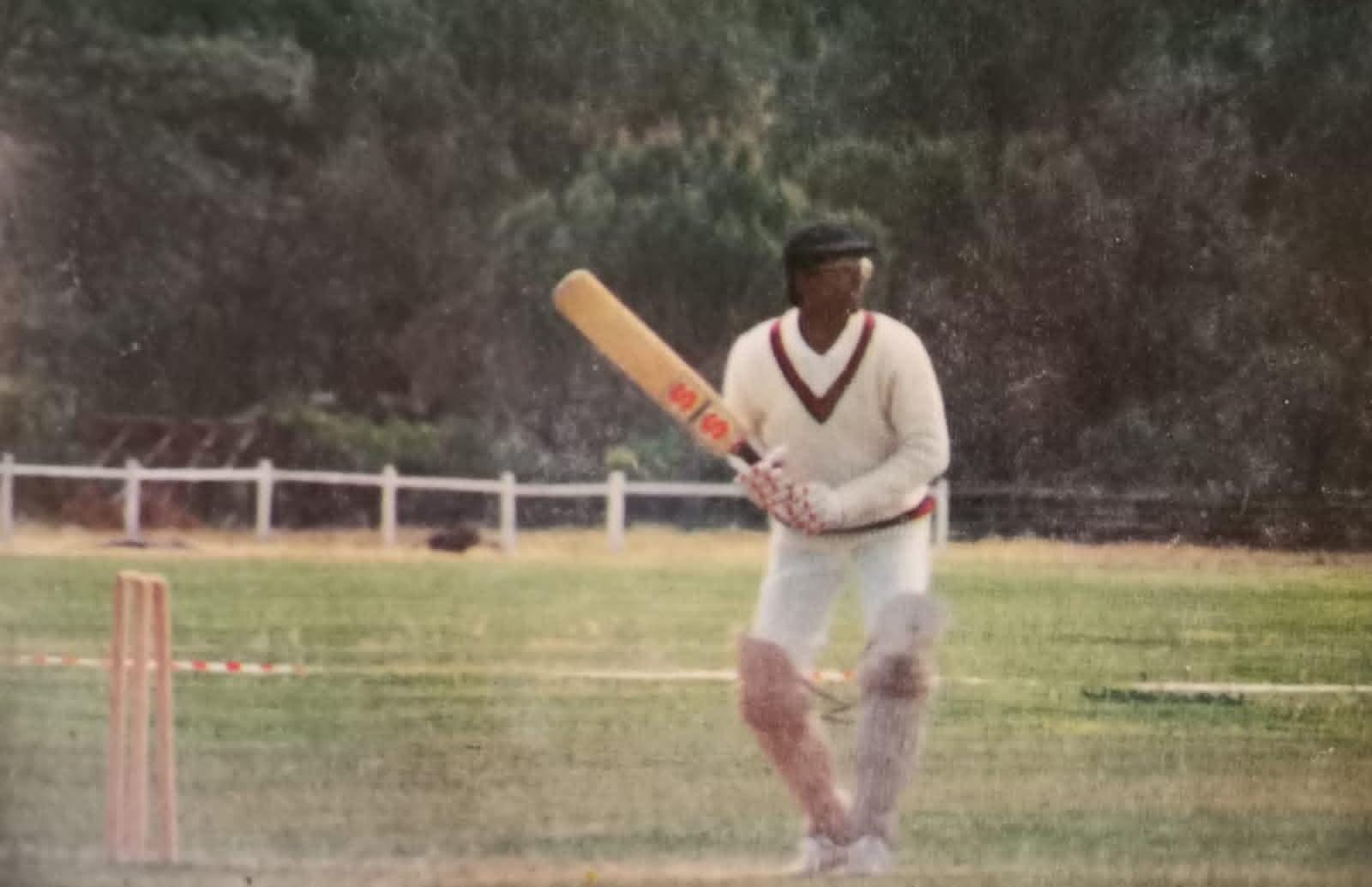

I began recruiting young Italians, coaching them, and organising structured training. From there, we gradually built the foundations — developing players, forming teams, and creating the structure that allowed cricket to take root in Italy. In 1984, I had the honour of captaining Italy in the country’s first official cricket tour — a tour of the United Kingdom. I went on to serve as captain of the Italian national team until 1994 and was last selected for the national side at the 1997 ICC Trophy in Malaysia.

I was also the first person of colour to captain Italy in any sport — something I regard not as a personal achievement alone, but as a reflection of how sport can transcend boundaries and create new possibilities. Looking back, I am proud that what began as a small, informal effort eventually helped establish cricket as an organised sport in Italy.

What was your sporting background in Sri Lanka?

My cricketing journey began in Sri Lanka. I studied at St. Patrick’s College, Jaffna, where I played cricket during my school years. The discipline, sportsmanship, and sense of commitment I learned at St. Patrick’s shaped me profoundly. In many ways, everything started there. The values instilled in me — respect for the game, teamwork, perseverance — stayed with me throughout my life and later guided my efforts in developing cricket in Italy.

How did you come to Italy?

After completing my Advanced Level examinations at St. Patrick’s College, I received a scholarship from a religious organisation to pursue higher studies in Italy. I arrived in Rome in 1968 to study mathematics. What began as an academic journey eventually became a lifelong association with Italy.

In 1968, virtually no one in Italy was speaking about cricket. What was the landscape like?

At that time, virtually no Italians were playing cricket. The game survived mainly within expatriate circles — particularly the British Embassy, the Australian Embassy, and officials connected to the United Nations. We used to play among ourselves in Rome, on a ground within the Villa Doria Pamphilj. It was largely informal — embassy teams playing one another in friendly fixtures, sometimes even what we jokingly called the ‘Rome Ashes.’ It was cricket sustained purely by passion.

In 1972, however, the park was handed over to the municipality, and the authorities informed us that cricket balls could no longer be used inside the grounds. We had to move nearly 15 kilometres outside Rome to find a small ground where we could continue playing. That relocation made things much more difficult. Sunday traffic was heavy, travel was inconvenient, and participation gradually declined. Often, we had to organise improvised matches — my team against the rest — simply to keep the game alive. This situation continued until around 1980.

What changed in 1980?

In 1980, I met Simone Gambino, who told me very clearly that unless we introduced cricket to Italians themselves, the sport would disappear once again. Many people do not realise that cricket in Italy actually predates football. The Genoa Cricket and Football Club, founded in 1893 at the British Consulate, still reflects that legacy in its name. However, during the Fascist era under Mussolini, cricket was sidelined, and football rose to dominance. Over time, cricket virtually vanished from Italian sporting culture.

So in 1980, we began a deliberate effort to revive cricket among Italians. By 1983, we had formed a cricket association. Simone brought young boys from schools, and I coached them. That same year, we travelled to England and played against local clubs. When we returned, towns began approaching us, asking how they could form their own clubs. Working with English and Italian teachers, we helped establish structured clubs. From there, the foundations were laid — and that is how modern Italian cricket began to grow.

Why did cricket decline during Mussolini’s era?

Cricket was strongly associated with England and British expatriate culture. During the Fascist period, the regime placed great emphasis on promoting sports that reflected nationalist ideals and projected a distinctly Italian identity. Cricket, viewed as an English game played mainly by expatriates and the elite, did not align with that vision. While it was never formally banned by law, it gradually lost institutional backing, facilities, and public attention. In practical terms, it became marginalised.

Football, by contrast, was actively promoted by the Fascist state as a symbol of national strength, discipline, and unity. Significant investment was made in stadiums, competitions, and international tournaments, which helped football expand rapidly across the country. Before that era, however, cricket had a meaningful presence in Italy. In those early decades, it was common for expatriates to play cricket in the summer and football in the winter.

In the 1980s, how did you introduce a game that most Italians had never heard of?

It was not easy at all. We began with Italian boys who travelled to England during their holidays. We encouraged them to watch cricket matches while they were there — to observe the game and understand it. When they returned to Italy, we coached them and gradually built small groups of players. Initially, we worked with older boys who could grasp the structure of the game more quickly. Later, we began approaching schools. Children were naturally curious and enjoyed learning something new.

The greater difficulty was convincing parents. Most of them had never heard of cricket and did not understand what the sport was about. Without public awareness, it was hard for families to support their children’s participation. That is why I believe events like the Olympic Games can help. When people see cricket broadcast on television at the international level, it creates visibility and legitimacy. Once parents understand the sport and see it recognised globally, they are more willing to allow their children to play.

There is a significant Sri Lankan diaspora in Italy. How have they contributed?

Very much so — especially in recent years. Italy has a sizeable Sri Lankan community, particularly a strong Sinhala diaspora, while the Tamil community is comparatively smaller. Many of them are actively involved in cricket. A good example is Crishan Kalugamage, who grew up in Marawila near Negombo. In the match against Nepal at this T20 World Cup, he took three wickets for just 18 runs and was named Player of the Match. That shows how members of the Sri Lankan diaspora are contributing meaningfully to Italian cricket at the highest competitive level.

When we first revived cricket in the 1980s, however, our primary focus was on developing the sport among Italians. We organised tournaments where Italian players competed against other Italian players. That was essential because we wanted cricket to take root locally and not remain confined to expatriate communities. It was through that foundation that Italy was eventually recognised internationally and included in ICC competitions.

To ensure proper development in the early years, we introduced regulations requiring each team to field at least four Italian players, and those players had to bowl a significant percentage of the overs. Today, the structure is more open and inclusive. Teams are required to include at least four under-23 players to encourage youth development, but participation is open to all communities. Italian cricket has become genuinely multicultural — Italians, Sri Lankans, Indians, Pakistanis, Afghans, and others are all part of the system. There are now around 50 clubs operating across Italy. For a country where cricket had nearly disappeared, that represents significant progress.

In the current Italian team, how many players are native Italians and how many come from diaspora backgrounds?

Most of the players in the current national team are Italian citizens, many of whom developed their cricketing skills abroad — in countries such as Australia, South Africa, and England. They hold Italian passports and are eligible to represent Italy. Some were born or raised overseas but retain Italian nationality, which allows them to play for Italian clubs and ultimately for the national team. In addition, a small number of players qualify through residency under ICC regulations. So the team today is a blend of Italian nationals — including those with overseas cricketing exposure — and resident players who have qualified under international rules.

How do you assess Kalugamage’s performance, particularly his leg-spin against Nepal? And are any of these players connected to your club?

Crishan Kalugamage is a very talented bowler. His control, variation, and particularly his ability to deceive batsmen with the googly make him a significant asset to the national side. Performances like the one against Nepal — where he dismantled their middle order and finished with three for 18 — demonstrate both his skill and temperament under pressure.

As for our club, several national-level players have developed within the Roma Capannelle system before progressing to represent Italy. One of the Mosca brothers, who opened the batting against Nepal, also came through our club. Over the years, coaching has remained central to my involvement in the game. I hold an England Level 3 coaching qualification. My son, Leandro Jayarajah, is also closely connected to the club — he currently captains the side and holds a recognised coaching certificate. He previously represented the Italian national team, including during the 2010 season.

How are the Italian government and the ICC supporting cricket now?

The ICC has been supportive, particularly in terms of development structures and international competition pathways. That support is important for associate nations like Italy, as it provides opportunities to compete, improve standards, and gain visibility. In Italy, cricket is recognised under the national sports system through the Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano, and there is institutional recognition, which is crucial for growth.

I believe the inclusion of cricket in the Olympic Games will make a significant difference. When a sport becomes part of the Olympics, it gains visibility, credibility, and broader public interest. If Italy qualifies or participates in Olympic cricket, it would bring enormous exposure. That kind of visibility can help attract young players, encourage parents to support their children, and potentially lead to greater institutional backing. For a developing sport like cricket in Italy, the Olympic platform could be transformative.

Italy’s 10-wicket victory over Nepal at the Wankhede — the country’s first-ever World Cup win. How did you receive that result?

It was a very significant moment for us. To be honest, we did not expect to win the match in such a dominant manner. Nepal is a strong and experienced side, and we knew going into the game it would be a serious challenge. But the boys performed exceptionally well. We bowled them out for 123 and then chased the target without losing a wicket in just 12.4 overs. Winning by 10 wickets was something nobody anticipated — not us, and certainly not many outside observers. It gave the players tremendous confidence and showed that Italian cricket has reached a higher competitive level.

You went to Italy to study mathematics, which could have led to a conventional academic career. Instead, you devoted much of your life to cricket — a sport with little recognition or financial reward at the time. Why?

Because I loved it. That was the only reason.

What message would you like to share with Jaffna Monitor readers, especially the younger generation?

Cricket is a very special sport. It teaches discipline, patience, respect, and friendship. Unlike many other games, even after a hard-fought match, players shake hands and remain friends. That spirit of mutual respect is at the heart of cricket.

To the young people of Jaffna and beyond, I would say this: choose a sport not for fame or money, but for the values it gives you. Sport shapes character. It teaches you how to win with humility and lose with dignity. Cricket, in particular, builds understanding between people from different backgrounds. It brings communities together. In today’s world, that spirit of friendship and unity is more important than ever.

If you love something — whether it is sport, study, or service — pursue it with sincerity. That dedication will take you further than you imagine.

Editor’s Notes

Francis Alphonsus Jayarajah co-founded the Doria Pamphilj Cricket Club (now Roma Capannelle Cricket Club) in 1978 alongside Massimo Brian Da Costa, Desmond O’Grady, and Sam Kahale. He served as the first captain of the Italian national cricket team from 1984 to 1994 and was last selected for the 1997 ICC Trophy in Malaysia. He currently serves as president of Roma Capannelle Cricket Club, one of Italy’s most decorated cricket clubs with five Serie A titles. His son Leandro Jayarajah currently captains the club.

Simone Gambino founded the Associazione Italiana Cricket on 26 November 1980 and served as its president for approximately three decades (1986–2016). He is now the honorary president of the Federazione Cricket Italiana. Italy gained ICC affiliate membership in 1984 and associate membership in 1995.

Crishan Kalugamage (born 16 June 1991 in Marawila, near Negombo) is a Sri Lanka-born Italian leg-spinner who plays domestically for Roma Cricket Club. He works as a pizza chef at La Vita pizzeria in Lucca, Tuscany. At the 2026 T20 World Cup, he claimed 3/18 against Nepal and was named Player of the Match.

Italy’s victory over Nepal (12 February 2026, Wankhede Stadium, Mumbai) was the country’s first-ever win at a men’s T20 World Cup and only the eighth 10-wicket victory in the tournament’s history. Italy joined the Netherlands as the only two non-British European teams to win a game in the men’s T20 World Cup.