In Sri Lanka Buddhism is often associated with the Sinhalese and the ancient capitals of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa and Kandy. There is no doubt that the Sinhala speaking people in general and many erudite monks in particular have largely been responsible for the preservation and growth of Buddhism in Sri Lanka for over two millennia. Historically however Buddhism also had a significant presence in South India and Northern Sri Lanka. Literary and archaeological evidence from South India and the Jaffna Peninsula provide a rich, yet under-appreciated, Buddhist heritage that shaped the spiritual and intellectual life of the region. The Upanishad (800-400 BCE) and its subsequent interpretive texts ‘Vedanta’(வேதாந்தம் or වේදාන්ත) were, complementary to the teachings of Buddhism and provided the spiritual framework for a selective – perhaps more critical, segments of Tamil society that was uncomfortable with aspects of Vedic Hinduism such as polytheistic deity worship, rituals and the caste system.

Advaita Vedanta: a bridge between Hinduism and Buddhism

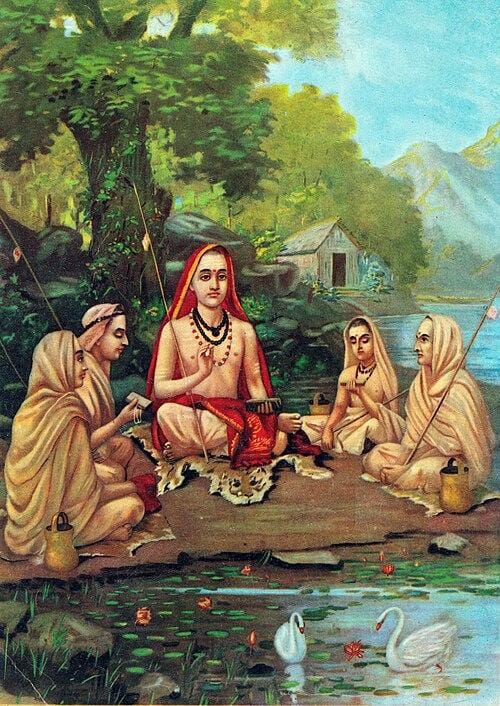

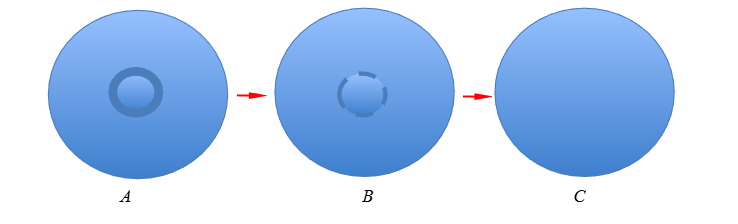

Popularised by Saint Sankaracharya in the 8th century, Advaita refers to a branch of philosophy that views the whole of creation as one living integrated whole (macrocosm, ‘Brahman’ or ‘Paramathma’). The individual life form (the microcosm or the ‘Jeevathma’) is an integral component within the endless and eternal ‘Paramathma’. The tendency to see the microcosm as a separate entity – separate from the macrocosm, is therefore a sensory illusion born out of ignorance (‘Maya’ or ‘Avidya’). When viewed in this light, the individual being has no beginning or end as it is always within that eternal and unchanging ‘Whole’. For a Vedantic Hindu therefore, existence is comparable to a wave within an ever - present ocean and a transient manifestation driven by external forces such as wind and gravity. In Vedanta these external forces are alluded to as ‘Karma’,. For a person embedded within this world view, there is no necessity for a deity or Brahminical rituals in order to pursue a ‘religious’ life. The segment of Tamil society who followed this path therefore had no conflict in reconciling their faith with the teachings of the Buddha based on ‘Samsara’ (cycle of existence), ‘Dukkha’ (suffering), ‘Avidya’ (Ignorance) and ‘Nirvana’ (Eternal bliss).

The spiritual journey

The spiritual journey of the Vedantic Hindu is to break the demarcation between the ‘Self’ and ‘Non-self’. Translating this knowledge, into the daily visceral experience however is no easy task as the divide is based on strong evolutionary instincts rooted in self-preservation. Four interconnected pathways were recommended for this purpose:

Selfless action or action free from the expectation of rewards (Also known as ‘Karma Yoga’)

Abject surrender to a personal god (Also known as ‘Bakthi Yoga’)

The use of Intellect and self-discipline (Also known as ‘Buddhi Yoga’ or ‘Raja Yoga’)

Introspection and meditation (Also known as ‘Gnana Yoga’)

Though the paths may be different based on an individual’s station in life (maturity, education, life experience etc.), the ultimate purpose was the same – the progressive loosening and the eventual dissolution of the dividing line between ‘self’ and ‘non-self’ in ones lived experience.

In this pursuit, commonalities with Buddhism far out-weigh the differences even though Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta are distinct spiritual traditions with important theological differences. Despite these differences, there exists a large intersection between the two and the inevitable cross fertilization of ideas as these traditions evolved.

It is therefore easy to understand the spread of Buddhism into South India and Northern Sri Lanka through trade routes, royal patronage, and missionary activity. Pallava and Chola kings – ardent Shivites, patronised Buddhist monks who established monasteries. For example, the Chinese monk Xuanzang, reported the presence of around 100 Buddhist monasteries and 10,000 Buddhist monks in the Pallava kingdom around 640 AD. Rajaraja Chola I (985–1014 AD) granted a village (Anai Mangalam) for the construction of the ‘Chudamani’ monastery at Nagapattinam. In this context, the Palk Strait served as a cultural bridge between South India and Sri Lanka as evident in the shared literary traditions and the presence of Buddhist shrines on both sides of the strait.

Buddhism and Tamil Literature

The influence of Buddhism within the Tamil speaking world is most vividly captured in Manimekalai and Kundalakesi – two of the five grand epics of Sangam literature and to a lesser extent in the third and perhaps the most popular of the grand epics – Cilappatikaram. One of the two major characters of Cilappatikaram - Madhavi, finally renounces her worldly life, gives away her wealth, and becomes a Buddhist nun. The other – Kannaki, despite being transposed as a member of the extensive Hindu pantheon of gods also found widespread acceptance amongst the Buddhists of Sri Lanka as goddess ‘Pattini’. Cilappatikaram - thought to have been composed between the 2nd and 6th centuries CE, illustrates the deep engagement of ancient Tamils with Buddhist philosophy.

Manimekalai: Manimekalai is a sequel to the Jain epic Cilappatikaram. It narrates the spiritual journey of Manimekalai, the daughter of Madhavi, who renounces worldly life to become a Buddhist nun. The island of ‘Manipallavam’, which becomes the home of Manimekalai during this period is thought to be Nainativu (or Naga Deepa), an island off the northern coast of Jaffna. The epic is a philosophical exposition, articulating key Buddhist doctrines such as karma, rebirth, and nirvana. It critiques materialism and upholds the ideals of compassion, non-violence, and moral discipline.

Kundalakesi: Though only partially preserved, Kundalakesi tells the story of a woman who, after a life of emotional turmoil, finds solace in Buddhism. The story line, based on the familiar mundane concepts such as forbidden love, marriage, betrayal and revenge also explores deep philosophical concepts such as ‘Karma’ (destiny), impermanence and suffering that arises through attachment to impermanence through ignorance. It expounds renunciation as the path to happiness.

These epics not only enriched Tamil literature but also serve to reinforce the extent to which core Buddhist principles were embedded within the Tamil-speaking communities.

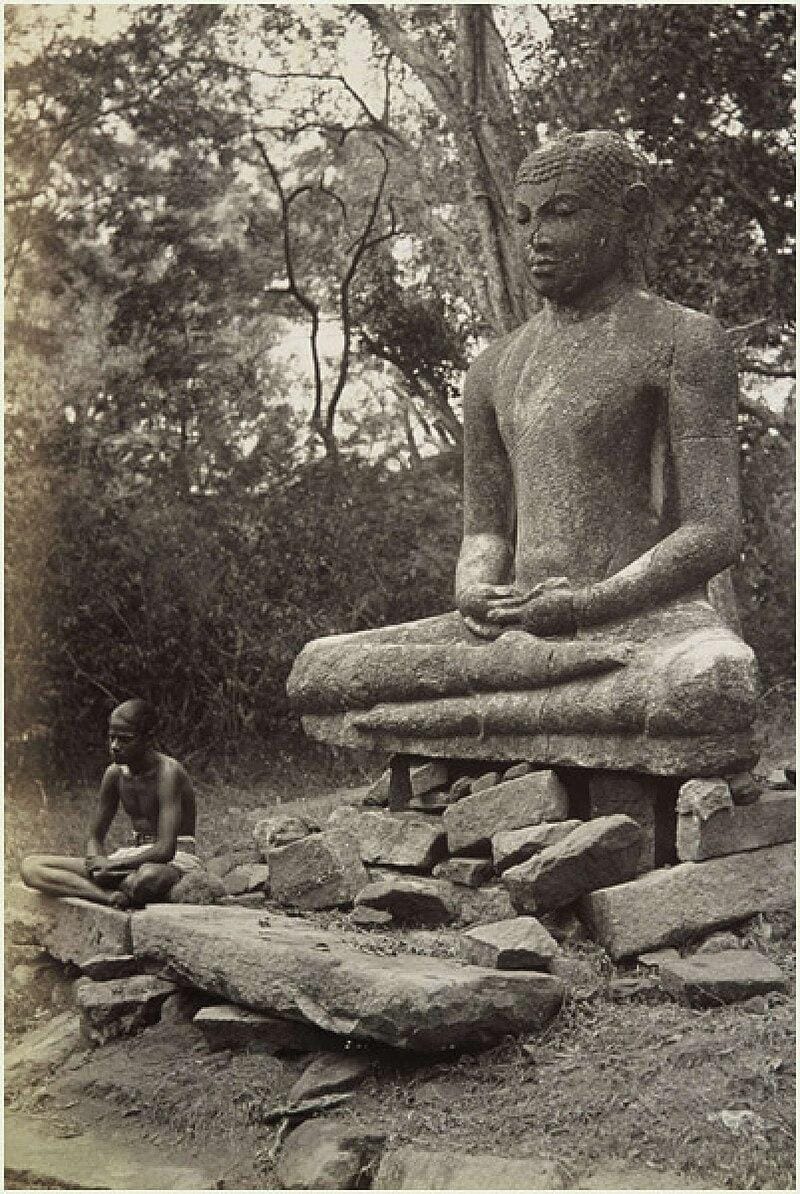

Northern Shrines of Kantharodai and Naga Deepa in Sri Lanka

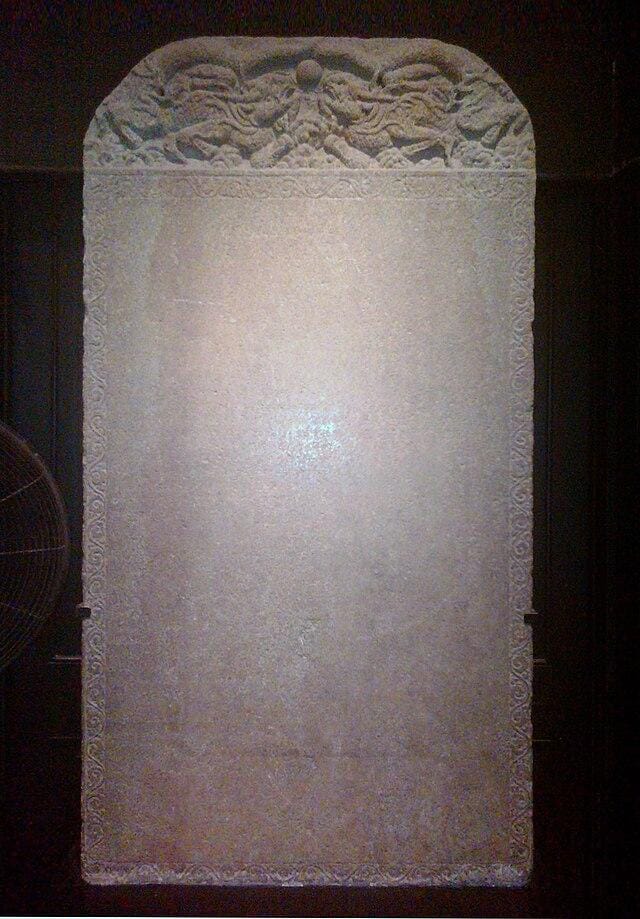

The literary legacy of Buddhism in Tamil is complemented by the enduring presence of ancient Buddhist shrines in the Jaffna Peninsula, particularly Kantharodai (Kadurugoda Viharaya) and Nainativu (Naga Deepa Purana Viharaya). Located in Chunnakam - near Jaffna, Kantharodai is one of the most significant archaeological sites in Northern Sri Lanka. The site, dating back to the Anuradhapura period, features clusters of mini stupas made from coral stone—an architectural style not found elsewhere on the island. Extrapolating from records in Mahavamsa, it has been suggested (though direct evidence is lacking) that Therini Sangamitta may have visited this site on her journey to Anuradhapura, carrying the sacred Bodhi sapling. Excavations in the early 20th century uncovered over 60 stupas, along with Buddha statues, Bodhisattva images, and ancient coins. Local legends – though unsupported by any credible evidence, refer to 60 Arhat Bhikkhus who perished in the area—either due to famine or poisoning and whose relics enshrined in the stupas. Today, about 20 stupas remain, standing as silent witnesses to the region’s once-thriving Buddhist culture.

Naga Deepa Purana Viharaya is Situated on Nainativu Island is one of the few sacred sites in Sri Lanka directly associated with the Buddha. According to oral tradition and the Mahavamsa, the Buddha visited Naga Deepa during his second journey to Sri Lanka, to mediate a dispute between two Naga kings over a gem-studded throne. His teachings brought peace, and the throne was enshrined as a symbol of reconciliation. Naga Deepa has remained a revered pilgrimage site for over two millennia. Despite the damages during the civil conflict, the temple has now been restored and continues to attract devotees from across the island.

The Bhakti movement and the decline of Buddhism in South India and Northern Sri Lanka

The rise of Bhakti (devotion) movement from around the period of the Pallava and Chola dynasties (6th century onwards) led to the gradual decline of Buddhism in Tamil speaking regions of South India and Sri Lanka. The ‘Nayanmars’ (the saints of Saivaism) and ‘Alvars’ (the saints of Vaishnavism) used the power of language and emotive musical compositions in praise of god - known as ‘Thevarams’ (தேவாரம் or තේවාරම් ) and ‘Pasurams’ (பாசுரம் or පාසුරම්) respectively, to reignite interest in devotion. The Pallava, Chola and Pandya kings in particular became ardent devotees of Shiva and Vishnu and royal patronage greatly supported the revival through the construction of impressive Hindu temples. The elaborate iconography enabled art forms such as Barata Natyam to become vehicles reinforcing devotion. In Sri Lanka, the political and religious shifts, particularly during the Chola invasions and the subsequent rise of the Jaffna Kingdom, further marginalized Buddhist institutions. Yet, the literary, ethical, and architectural legacies of Buddhism remain strongly embedded in Tamil culture with non-violence, compassion, and renunciation resonating strongly. The four stages of Hindu life (‘Brahmacharyam’ (or stage of learning), ‘Grahastam’ (stage of family life and sensual pleasure), ‘Vanaprastam’ (stage of detachment) and ‘Sannyasam’ (stage of renunciation) – as in Buddhism, emphasize the impermanence of the material world and renunciation as the path to spiritual freedom.

In conclusion, the story of Buddhism in ancient Tamil literature and Northern Sri Lanka is one of shared heritage, cultural synthesis, and spiritual depth. This perspective offers a reminder that the island’s Buddhist past is not confined to the South alone but is also deeply rooted in the Tamil-speaking regions of the north. Acknowledging this shared history is essential for a deeper understanding of Sri Lanka’s pluralistic identity and the history of co-existence that must not be distorted for parochial electoral gains.

Comment: The ideas expressed in this article are that of the author and do not reflect the views of the University of Manchester.