The dead do not speak - but the earth does

A few years ago, I visited Cambodia. My original aim was to see the Angkor Wat temple complex. But, as always, my journalistic instincts led me deeper into rural Cambodia, where I found myself in quiet conversations with a few former soldiers of the Pol Pot regime, now living ordinary lives as toddy tappers, farmers, and small shop owners.

One of them - a former henchman of the Khmer Rouge - opened up after a few glasses of toddy. In a hauntingly calm voice, he described how they were ordered to kill anyone seen as an enemy of the communist revolution. And then, with a chilling emptiness in his eyes, he told me how they would fry and eat the pancreas of the dead at night, washing it down with country-made rice wine.

As he poured himself another drink, he leaned closer and said: "You know, there’s a saying in Cambodia The dead do not speak - but the earth does."

He paused, his voice dropping to a whisper: "It means, wherever you dig - to build a house, to dig a well, even a toilet - you may unearth human remains. That’s how we wreaked havoc on this land," he confessed, with a strange mixture of guilt and detachment. That grim truth - the dead do not speak, but the earth does - is not Cambodia's alone. Once again, the cursed soil of Jaffna's Chemmani has whispered its dreadful testimony: "We are no different."

Nineteen skeletons - or rather, nineteen souls

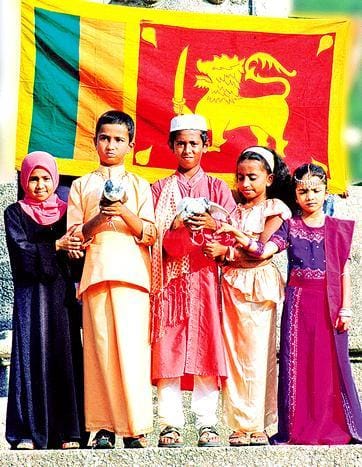

Nineteen skeletons - or rather, nineteen souls who once breathed, loved, and hoped. Among them, the fragile remains of an infant - tiny bones that never had the chance to grow, a life extinguished before it could even begin to grasp the world's cruelty. This baby knew nothing of the LTTE. Nothing of the Sri Lankan Army. Nothing of politics, flags, or ethnic divisions. Its only "crime" was being born from a Tamil mother's womb - in a land where, for some, that alone was enough to seal their fate.

How many more silent graves lie beneath the bloodied earth? How many more infants, neonates, and mothers will emerge as we peel back the layers of dirt that have long concealed Sri Lanka's crimes? The question hangs heavy - and the earth, patient and merciless, will keep answering.

When a Schoolgirl’s Death Exposed a Nation’s Machinery of Death

The story does not begin with excavations. It begins with the savage destruction of an 18-year old girl's dreams. On September 7, 1996, Krishanthi Kumaraswamy - a brilliant student of Chundikuli Girls' College who dreamed of becoming a doctor - was dragged from a military checkpoint into a nightmare that would expose the industrial-scale machinery of death operating in Sri Lanka's north.

Eleven uniformed predators gang raped this young woman, dismembered her, and buried her broken body like garbage in a shallow pit. When her 16-year-old brother Pranavan, her mother Rasamma, and family friend Kirupakaramoorthy dared to search for her, they too were abducted, butchered, and dumped into Chemmani's cursed soil.

But Krishanthi's murder refused to vanish into the abyss of state sponsored denial that had swallowed thousands of other Tamil lives. Too many people had seen her stopped at that army checkpoint. She was a schoolgirl from an educated, respected family; the community could not be silenced. Her brutal killing became a burning torch that illuminated the machinery of darkness through which the Sri Lankan state conducted its campaign of mass killings.

Testimony Written in Blood

I know these horrors not as distant headlines, but as memories that live within my own blood. During the same period when the Chemmani atrocities were unfolding, I once accidentally met a distant relative of mine. She was performing adiyadithal - a painful vow where the devotee repeatedly prostrates around the temple premises, pleading with the gods - at Nallur Veeramakali Amman Temple. One round itself is exhausting, but she was doing three rounds every day. She was visibly drained. When I gently asked her why she was doing this, she whispered that her younger brother had been taken by the military for "investigation" and had not yet returned. She was invoking the divine, hoping against hope that her brother might somehow return alive. But to this day, he never came home. His fate remains unknown, perhaps lying beneath one of the very mass graves we are now unearthing. His sister still waits - waiting for a brother who will never again walk through her door.

Another distant relative - a widow whose only son, an innocent young man who was the center of her world - watched helplessly as military personnel arrested her boy. Unlike my other relative, her son was eventually released after several weeks of detention. When he returned home, his grieving mother thought her prayers had been answered. But the young man who came back was not the same boy who had been taken. For days, he vomited and passed blood, his body carrying the invisible scars of whatever horrors he had endured in custody.

Within a few days, he died. Even now, I can still hear the raw, haunting screams of his mother at his funeral - a sound that never fades. The kind of wailing that pierces your soul, a grief so deep it leaves you gasping in helpless rage. I remember when my own family - like thousands of others - was displaced as the Army captured Jaffna in late 1995 and early 1996. President Chandrika Kumaratunga had ordered a massive military operation to recapture the peninsula, and the Army advanced with overwhelming force. But the LTTE, unwilling to allow the military a propaganda victory by capturing Jaffna with its civilians inside, ordered the entire population to evacuate. They wanted Chandrika to capture a ghost city - and, of course, they wanted to keep the people with them, a brutal strategy they employed until their final days in Mullivaikal. As the Tamil poet Sugan would later write, "Prabhakaran took even the 80-year-old grandmother from Jaffna for his safety."

We became part of that endless stream of displaced souls. For six months, we lived scattered and uprooted, uncertain of where life would take us next. Later, as the LTTE moved its operations into the Wanni jungles, they urged the displaced families to follow. I still recall - I was just a child - standing, if I remember correctly, somewhere near Chavakachcheri, where LTTE cadres stopped us, warning: "If you go back, your sons will be tortured, your daughters will be raped."

But like Krishanthi's family, and like many others who badly wanted to go back to Jaffna - and perhaps still clung to a fragile hope in the Sri Lankan state - we chose to return to Jaffna. And I also know - because I have seen it with my own eyes - how this one heinous crime of raping and murdering a schoolgirl terrified hundreds of Tamil youth across Jaffna. Many of them, broken and enraged, eventually joined the LTTE with one desperate purpose: to defend the dignity of their sisters, at a time when the state itself had become the predator - or, worse, the concealer of predators.

Among them was a fragile youth - a boy people used to joke about, saying he couldn’t even bite a betel leaf. He was soft-spoken, shy, and unable to argue with anyone. But after Krishanthi's brutal murder, something inside him broke. Disturbed and consumed by rage, he joined the LTTE. Years later, I heard that he had become a suicide bomber. Such was the chain of horror this single crime unleashed.

Death Row Confessions: The Architect of Annihilation Speaks

Before the Rajapaksa brothers would later devastate the Tamil people on a grander scale, it was Somaratne Rajapakse - not a politician, but an ordinary Lance Corporal of the Sri Lankan Army. He was the man who stopped Krishanthi at the army checkpoint on the Jaffna-Kandy Highway at Kaithady that day, and who, along with his fellow military personnel, raped and murdered her, then butchered her family.

Before sentencing him to capital punishment for his unspeakable crimes, the judge asked whether he had anything to say. Somaratne Rajapakse chose revelation over silence. Perhaps he felt remorse, or perhaps he thought: why die alone when men far more powerful than me committed even worse crimes? In a confession that should have shattered Sri Lanka's carefully constructed edifice of denial, he exposed the Chemmani killing fields and told the world of the blood-soaked soil where 400 to 600 young Tamil men and women had been systematically abducted, murdered, and buried. Rajapakse didn't merely point to unmarked graves - he named names.

He identified the puppet masters behind this machinery of killing. He revealed operational details, chains of command, and the bureaucratic precision with which living human beings were processed into corpses and statistics.

"Almost every evening, dead bodies were brought there [to the Ariyalai SLA camp] and the soldiers were asked to bury them," Rajapakse testified. A friend of mine who lived in Ariyalai often recounts how they would hear painful, helpless cries almost every evening. A girl later wrote on social media how her mother, terrified by the sounds, would never step out of the house after 5 p.m. and never allowed her children to go outside.

The Continuity of Carnage: From JVP to Tamil Genocide

The Chemmani killings weren't aberrations-they were the logical evolution of a system perfected during the late 1980s annihilation of 60,000 Sinhala youth in the JVP insurgency. The same security apparatus, the same operational methods, the same culture of absolute impunity were simply redirected from southern Sinhala villages to northern Tamil communities. Sooriyakanda mass grave, containing the corpses of murdered school children, demonstrated that the state's appetite for young blood transcended ethnic boundaries. The institutions that had consumed Sinhala youth were never dismantled-they were merely retooled for a new harvest of Tamil victims.

The Theater of Simulated Justice

Sri Lanka has mastered the art of "simulated transitions" elaborate performances that mimic accountability while preserving impunity. The Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, the Paranagama Commission, and countless other bodies have produced towers of paper that serve as tombstones for buried truth.

These mechanisms follow a depressingly predictable script: initial promises of transparency, comprehensive documentation of atrocities, international praise for "progress," and eventual abandonment of all accountability measures. The performance is always the same, whether the victims were JVP supporters in the south or Tamil civilians in the north.

Critics might argue that these commissions serve important functions - providing platforms for victim testimony, creating historical records, and maintaining international engagement. This perspective deserves acknowledgment. Yet the pattern is unmistakable: decades of commissions have produced libraries of documentation but not a single high level prosecution.

A Blueprint for Breaking the Cycle

The families who have spent decades searching for their disappeared deserve more than hollow condolences and political theater.

Today, power rests with a government led by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). And the JVP, if anyone, knows what it means to lose loved ones to state terror. They know the agony of mass graves, of enforced disappearances, of a brutal state machinery that once turned its guns on their own youth. They know precisely how state machinery manufactures death with surgical cruelty.

Will this government - born of a movement that once suffered the full force of state violence - finally break the cycle? Will they deliver justice to the Tamil victims of Chemmani, whose families have waited for decades? Or will they, too, follow the same familiar script: commissions without consequence, reports without accountability, and silence without justice - just as every government before them has done? Only time will tell. But history will not be forgotten. And the earth will not stop speaking.