By M.R. Narayan Swamy

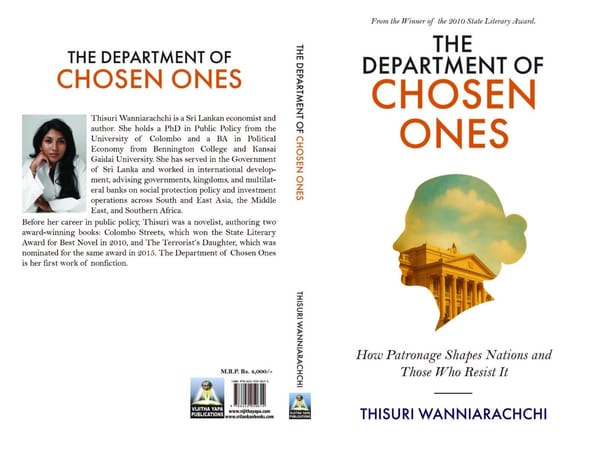

When kings become authoritarian and develop disdain for their subjects, their kingdoms collapse. This is what happened in modern Sri Lanka when a president and his kin presided over the picturesque country as if it were family property. A child prodigy who grew to be an insider with a conscience, Thisuri Wanniarachchi, unveils the story in a most chilling and gripping manner.

Thisuri was just 15 when she bagged Sri Lanka’s most prestigious literary award for her first work of fiction. Despite not hailing from a privileged family, she got into the best schools in Colombo with distinction, later securing a fully funded education at one of the world’s most expensive universities. Her innate talent led her to advise presidents in Sri Lanka and draft national strategies when she was only in her 20s. She was confident that radical changes could be ushered, considering the way the country was (badly) governed. She was an idealist.

Yes, some notable successes did come her way, benefiting a large segment of the population. But eventually, after encountering many roadblocks, she realised that the system was unlikely to change — whether the rulers were the entrenched Sinhalese elite or diehard Marxists whom destiny had catapulted to power after decades on the fringes of politics.

By the time she resigned from the government, with a heavy heart, Thisuri had imbibed many lessons: about poverty, corruption, patronage, nepotism, political appointees, and the collusion between entrenched vested interests and politicians, among others. She began to understand why economic policies had gone so far off track that they fuelled poverty instead of curbing it — and why people kept re-electing the same ineffective, self-centred politicians who failed them again and again. This was raw political science.

To begin with, she interned at the Sri Lankan President’s Office in 2015. She later served as Assistant Director for Sustainable Development. As the National Coordinator for Vision 2030, she was entrusted with the reins of the administration’s flagship policy initiative.

She had many ideas, and there were well-meaning officials within the administration. But there were also unscrupulous hangers-on and well-connected manipulators. They spoiled the show.

Thisuri’s raw courage — she was the daughter of an army officer — and her intellect helped her grow wiser rapidly. The lessons came — some slowly, some swiftly — but all were eye-openers.

Corruption in Sri Lanka, she concluded, was not incidental or peripheral; it was systemic, woven deeply into the operations of governance. The country remained trapped within a political economy where institutions were designed not to deliver justice, efficiency or impartial service, but to distribute favours and entrench privilege. The system rewarded loyalty over competence, connections over ability, and survival over genuine public service. The system, smelt from within, stank.

A mentor from an earlier political era helped Thisuri to come to grips with the pain of poverty – camouflaged by the post-war bright lights of Colombo. This is when she stopped seeing poverty as a social problem and began viewing it as a systemic disease. Politicians and officials carried deeply embedded prejudices about the poor. The government fought the poor instead of fighting poverty, more so if the poor were from the tea-growing estates (so-called Indian Tamils) or from the worst hit regions of the previous war theatre in the northeast.

Across the public sector, enterprises were riddled with inefficiencies. There was a vested interest-fuelled passionate objection to the private sector. Political interference was rampant. This is why a senior official as sincere as Austin Fernando quit the government.

Some good men occupied vital seats but the system rarely bent to sound policies, a few exceptions apart. The political system itself was often dysfunctional. This is why Islamist terrorists blew up 269 people on Easter Sunday in 2019 although the government had precise warnings about the impending disaster. But Thisuri kept batting.

Sri Lanka’s top political actors were a mixed bag. Some were revolting. Under Mahinda Rajapaksa, who crushed the Tamil Tigers and acquired the status of a living God, the state ceased to be a republic – it was a dynasty in motion. Maithripala Sirisena, who broke ranks from Mahinda to acquire presidency, began with a promise but his liabilities were far too many. Sajith Premadasa was sincere but did not earn the status of a challenger and ruler.

Ranil Wickremesinghe had his qualities but proved a failure. Thisuri was out of the government by the time the Janatha Vimukti Peramuna (JVP, or People’s Liberation Front) took office. But theirs is a politics built not on knowledge but on grievance; not on aspiration but on resentment; not on proven abilities but on promises made. Many in the JVP leadership, she says, are “insulated, incurious and proud of it”.

Thisuri admits she was sobered by her years in the government. But she acquired the most important lesson of all: an incurable cancer had gripped the system. Political patronage had seeped into every layer – from promotions to transfers to strategic appointments. Patronage was not just tolerated – it was ritualized. Ministers often employed sons as heirs, and they answered to no rulebook but their own.

And this is what the author dubs the Department of Chosen Ones. “It isn’t a government ministry or a formal agency. It is the invisible institution that exists everywhere – public service, private sector, politics (and) development. An elite department that recruits by bloodline and proximity, not by merit. Its members don’t apply. They are inducted. For the rest of us, the department is closed.” This subject also lay at the heart of her PhD.

Thisuri paid the price for being a woman, one with a mind of her own. When she resigned from the President’s Office, tabloids accused her of loose morals. “The list of men I was accused of sleeping with read like a multiparty coalition with a two-thirds majority – if it were true.” She was hurt but she did not allow the muck to derail her career. Thisuri sailed into the World Bank and saw the world. But that is another story.

This book is so enthralling that I read 250 pages at one go – and finished the rest the next morning. I have not read a more mesmerizing book on Sri Lanka’s ugly realities. All Sri Lankans and anyone sympathetic to that country must read this political bible.

Title: The Department of Chosen Ones: How Patronage Shapes Nations and Those Who Resist It; Author: Thisuri Wanniarachchi; Publishers: Vijitha Yapa Publications (Colombo); Pages: 353; Prices: Rs 4,000 (SLR)