There exists a particular species of political betrayal that cuts deeper than ordinary duplicity. It occurs when those who survived state terror become its architects, when victims of arbitrary detention design new systems of indefinite imprisonment, when revolutionaries who once faced torture codify powers enabling it. Sri Lanka stands at precisely such a moment.

The National People’s Power government—led by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, a party whose members were “disappeared,” tortured, and extrajudicially executed by the thousands under emergency laws in the 1980s—now proposes legislation that would have made their own historical suppression even more efficient, more legally unassailable, more total.

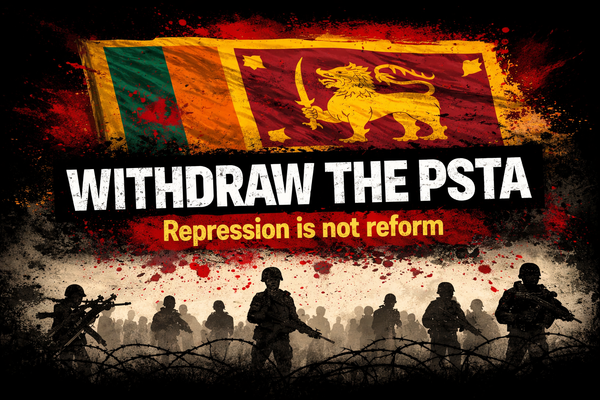

The Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), presented as the promised replacement for the notorious Prevention of Terrorism Act, represents not reform but refinement of repression. It is the PTA reborn with 21st-century surveillance capabilities, expanded definitions, and a veneer of procedural legitimacy designed to obscure its authoritarian core.

This is not hyperbole. This is the assessment of constitutional lawyers, human rights organizations, international legal bodies, and—most damningly—the NPP’s own past positions when it challenged similar legislation from opposition benches.

The Promise That Became a Lie

The NPP’s 2024 election manifesto could not have been clearer: “Abolition of all oppressive acts including the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), and ensuring civil rights of people in all parts of the country.”

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake told international media his government would end “indefinite detention, establish judicial oversight for all detentions, protect the right to legal counsel,” and ensure any new legislation would meet “international human rights standards.” These were not vague aspirations but specific, measurable commitments.

The draft PSTA violates every single one of them.

PSTA preserves indefinite detention—up to two years without charge. It maintains executive rather than judicial control over detention decisions, with a Defence Ministry official empowered to imprison citizens without court authorization. It creates new categories of criminalized speech, surveillance powers, and mandatory informant obligations that international human rights law explicitly prohibits.

The PTA’s 46-Year Reign of Terror

To understand why the PSTA represents such a profound betrayal, one must grasp what the PTA actually did to Sri Lankan society.

Enacted in 1979 under President J.R. Jayewardene as a supposedly “temporary” six-month measure, the PTA became permanent in 1982. For 46 years, it has been the legal foundation for systematic human rights violations on an industrial scale.

The law’s provisions read like a manual for authoritarian control:

Administrative detention for up to 18 months without judicial oversight—meaning a Defence Ministry bureaucrat, not a judge, decides who stays locked up. In practice, detention often extended far beyond 18 months through rolling Emergency Regulations or simply ignoring legal limits. Hundreds spent years, even decades, in custody without ever facing trial.

Confessions to police officers admissible as evidence—a provision that effectively legalized torture. When police can secure convictions based solely on statements extracted in custody, without independent verification before a magistrate, the incentive structure for abuse becomes overwhelming. Countless PTA detainees bear the physical and psychological scars of interrogations designed to produce confessions rather than truth.

Criminalization of “unlawful activities”—defined so broadly that peaceful political activism, journalism critical of security forces, or simply being Tamil in the wrong place at the wrong time could trigger arrest. The law required no actual violent act, no material support to militants, merely suspicion of harboring “unlawful” intent.

Failure to inform police as a criminal offense—turning every citizen into a potential informant under threat of imprisonment. Journalists protecting sources, lawyers maintaining client confidentiality, doctors respecting patient privacy, clergy hearing confessions—all faced years in prison if authorities deemed them insufficiently cooperative.

The human cost defies comprehensive accounting. Tens of thousands arrested. Thousands tortured. Hundreds “disappeared.” Families torn apart. Communities terrorized into silence.

The PTA has repeatedly been wielded against dissenters with devastating consequences. It was used against journalist J. S. Tissainayagam, imprisoned for 18 months and sentenced to 20 years for articles critical of government policy toward Tamils—a conviction later overturned only after intense international pressure. It was used against student activist Wasantha Mudalige, detained for five months in 2022 for organising protests and released only after a magistrate ruled that the Terrorism Investigation Division had misused the terror law. It was used against poet Ahnaf Jazeem, jailed for 18 months on the absurd claim that his Tamil-language poetry “promoted extremism”—an allegation that collapsed under scrutiny, but only after his education was derailed and his family traumatised.

These are the known names—cases that reached courts, headlines, and international scrutiny. But during the height of the war, the PTA was deployed far more brutally and routinely against hundreds of Tamil civilians: students, labourers, returnees from abroad, and young men picked up in mass cordon-and-search operations. Many were held for years without charge, some disappeared into prolonged detention, others were released without apology or explanation—their lives permanently scarred. For most, there were no lawyers, no media coverage, and no global campaigns.

The PSTA: Same Repression, New Branding

The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA) doesn’t reform this architecture of abuse. It modernizes it, expands it, and provides fresh legal cover for future atrocities.

Terrorism Defined to Criminalize Dissent

The PSTA defines terrorism as acts committed “intentionally or knowingly” with any of four purposes:

Provoking terror in the public

Intimidating the public or section of public

Compelling the Government of Sri Lanka or any other government to do or abstain from doing any act

Propagating war or violating territorial integrity

That third category—compelling government action—is a masterclass in authoritarian lawmaking. By this standard, every protest, every petition, every advocacy campaign seeking policy change becomes potential terrorism. Union strikes demanding wage increases? Compelling government action. Civil society campaigns against IMF austerity? Compelling government action. Diaspora advocacy against human rights abuses? Compelling foreign government action.

The draft includes an exclusion clause stating that protests and strikes, “by themselves,” do not constitute terrorism. But this fig leaf offers no real protection. As a lawyer explained to me, “If someone calls on the government to withdraw from the destructive IMF agreement, they could be arrested as a terrorist. Likewise, urging a foreign country—such as India or any other—to cancel agreements signed with Sri Lanka could also be labelled terrorism.”

The exclusion sits in direct tension with the broad definitions elsewhere. A government determined to crush dissent—and Sri Lanka has extensive historical experience with such governments—will invoke the compelling-government-action provision and simply ignore the exclusion as inapplicable to the specific case.

International human rights law requires terrorism definitions to satisfy cumulative criteria: there must be an act of serious violence—such as bombings or armed attacks—and a specific intent to terrorise civilian populations or coerce a government. Both elements are essential.

The proposed PSTA abandons this framework. It requires only one of several broadly defined intents, coupled with consequences that need not involve violence at all, including acts such as the “serious obstruction of electronic systems” or the “disruption of essential services.” Under this formulation, conduct that is disruptive, political, or protest-related—but not violent—can be reclassified as terrorism.

This approach fails every recognised international standard governing the definition of terrorism. It is not an oversight, a drafting error, or a technical lapse. It is a deliberate departure—one that lowers the threshold of terrorism precisely so that extraordinary powers can be applied to ordinary acts of dissent.

Executive Detention Preserved and Extended

Despite President Dissanayake’s explicit promise of “judicial oversight for all detentions,” the PSTA maintains executive control over imprisonment.

The Inspector General of Police can detain anyone by obtaining approval from the Secretary to the Ministry of Defence—a presidential appointee, not an elected official, and certainly not a judge. Initial detention lasts two months, extendable to one year from arrest. Combined with remand periods during any eventual trial, the law permits up to two years of detention without conviction.

The law mandates notifying the Human Rights Commission within 24 hours and provides for periodic magistrate visits to detention facilities. But decades of PTA experience prove such safeguards are theater. The HRCSL, while occasionally effective when it can mobilize public pressure, lacks enforcement powers. Magistrate visits, when they occur, involve checking boxes on forms while detainees remain too terrified to complain about torture or abuse while still in custody.

Legal experts have observed that “when safeguards are flouted, significant resources are required to obtain a remedy, such as moving the Supreme Court.” In practical terms, this means safeguards function only for those with money, legal knowledge, and access to civil society networks. For the vast majority of detainees—especially those from poor and minority communities—these protections are largely illusory, leaving them effectively defenceless against prolonged detention and abuse of power.

The PSTA also introduces a sinister new mechanism: “deferred prosecution” deals under Clause 56. The Attorney General can offer suspects rehabilitation in lieu of prosecution—but only if they admit guilt. This creates a coercive choice: confess and enter a two-year rehabilitation program (effectively detention without trial), or maintain innocence and face a decade in prison if convicted.

This is plea-bargaining as state extortion. It enables the government to punish individuals through “rehabilitation” without proving any case in court, extracting confessions through leverage rather than evidence. Suspects could be held in legal limbo for years, with cases hanging over their heads indefinitely, as one critic noted the law could allow the AG to pressure someone “for 20 years” with an unresolved case.

Criminalizing Journalism and Information

Perhaps the PSTA’s most Orwellian provisions criminalize information gathering and dissemination on national security grounds.

Clause 8(2) makes it a terrorism offense to gather or supply “confidential information” if one knows or suspects it could be used to commit a terrorist act. Conviction carries up to 15 years imprisonment and Rs. 15 million in fines.

“Confidential information” is defined as “any information, the dissemination of which is likely to have an adverse impact on the national security and defence of Sri Lanka” and “any information relating to the police or armed forces, regarding the conduct of any official activity.”

This language criminalizes investigative journalism. A reporter documenting military land grabs in the North? Gathering confidential information. A civil society organization compiling testimony about torture in police custody? Potentially aiding terrorism by exposing security force conduct. A researcher obtaining leaked documents about defense procurement corruption? Up to 15 years in prison.

Critically, the 2023 Anti-Terrorism Bill included a good-faith defense for “bona fide journalists, academics, or researchers” handling such information in the public interest. The PSTA removes this protection entirely. The omission is not accidental—it is a deliberate choice to maximize the law’s utility for suppressing documentation of state abuses.

Clause 10 compounds this by criminalizing “terrorist publications”—any content “likely to be understood as encouraging or inciting terrorism,” including by “recklessness.” You don’t need to intend to promote violence; being careless about potential interpretations is sufficient for up to 20 years imprisonment.

This invites prosecutors to impose the worst possible reading on political commentary, historical analysis, or advocacy. Would publishing a profile of a militant leader’s motivations constitute “glorification”? Would arguing for negotiations with armed groups be “indirect encouragement”? The law’s vagueness ensures maximum prosecutorial discretion and maximum self-censorship.

Surveillance State Infrastructure

The PSTA establishes a legal framework for mass surveillance unprecedented in Sri Lankan law.

It authorises authorities to intercept, monitor, and decrypt electronic communications in the name of terrorism investigations. Police are empowered to compel any individual to surrender mobile phones, computers, and access credentials, while officers of a designated rank may examine devices and communications at any time, with courts largely sidelined and unable to exercise meaningful oversight.

The result is the effective destruction of digital privacy. Messaging apps, emails, social media activity, location data, and even financial transactions become vulnerable to warrantless search and seizure, triggered merely by an allegation or suspicion of terrorism.

Section 15 makes everyone a mandatory informant: failing to report terrorism-related information carries up to seven years imprisonment. This conscripts doctors, lawyers, journalists, and clergy as state surveillance agents, forcing them to choose between professional ethics and criminal liability.

The cumulative effect is a surveillance society where the state has access to all communications, all devices, all information—and where silence itself becomes criminal.

Militarised Powers Without Emergency

The PSTA embeds as permanent, routine law a range of powers that, under Sri Lanka’s previous legal framework, were most expansively exercised through Emergency Regulations alongside the PTA. Military personnel are granted enhanced authority to stop, search, arrest, and detain civilians, often with minimal or delayed judicial oversight, blurring the line between civilian policing and military power.

The Defence Secretary is empowered to declare “prohibited places” by gazette, rendering mere entry a criminal offence. Senior police officers may impose “restriction orders” that closely resemble forms of administrative detention or house arrest. The President may unilaterally proscribe organisations, with association or support for such groups, exposing individuals to serious criminal liability.

While the PTA itself made certain extraordinary powers permanent, their most extensive use historically occurred under time-bound emergency declarations, which at least required periodic parliamentary renewal. The PSTA removes even this procedural constraint, normalising an expanded security state as routine governance and dispensing with the constitutional fiction that such measures are justified only in moments of exceptional crisis.

The NPP’s Staggering Hypocrisy

In 2023, when the Wickremesinghe administration proposed similar anti-terrorism legislation, NPP luminaries, including Vijitha Herath (now Foreign Minister), Wasantha Samarasinghe, and Eranga Gunasekara, filed Supreme Court petitions challenging the law as unconstitutional. Herath declared: “The anti-democratic, constitutional violation act should be withdrawn immediately.”

The NPP’s specific objections then mirror civil society’s objections to the PSTA now. Herath criticized vague definitions that could brand COVID-19 health measures as terrorism, arguing this would enable scapegoating of minority communities. He warned against criminalizing disruption of essential services, noting how easily this could be weaponized against labor strikes.

Every objection the NPP raised in 2024 applies with equal force to its own 2025 draft. The party that demanded withdrawal of “anti-democratic” legislation now expects civil society to accept substantially similar provisions because trust us, we’re the good guys?

The historical irony cuts even deeper. During the 1987-89 JVP insurrection, the UNP government used emergency laws and extra-legal violence to crush the movement. Thousands of young JVP members were “disappeared,” executed without trial, burned in tire pyres. The party commemorates these victims as martyrs, holds annual remembrance ceremonies, and builds its moral authority on that history of state brutality.

Yet the PSTA would have made that repression more efficient. As one legal analyst noted, “If such extraordinary powers had been in the hands of the UNP Government during the JVP’s 1980s insurrections, the hands of even the bravest judge would have been tied.”

The JVP’s dead would have had even less legal recourse. Detention orders, restriction orders, surveillance, mandatory informants—all the tools the PSTA provides would have enabled more complete suppression of the very movement that now controls government.

How does a party reconcile venerating its own martyrs while constructing legal machinery to create new ones?

The Predictable Victims

There is no mystery about who will bear the brunt of PSTA enforcement.

Tamil communities in the North and East, still living under heavy military presence 16 years after the war’s end, already know how “terrorism” laws target them. Documentation of land grabs, advocacy against ongoing militarization, commemoration of war victims—all risk being branded terrorism under the PSTA’s expansive definitions. The law’s language about “propagating war” or threatening sovereignty can be twisted to accuse Tamil rights advocates of reviving separatism.

Muslim communities have faced intensifying discrimination, profiling, and surveillance, particularly since 2019. That same prejudicial logic—now reinforced by the PSTA’s vastly expanded powers—risks being institutionalised, making the recurrence of such abuses not an aberration but an inevitability.

Journalists and human rights defenders who document state abuses, expose corruption, or challenge official narratives will face criminalization. The law’s provisions on “confidential information” and “terrorist publications” are tailor-made for silencing investigative reporting and critical commentary.

Labor activists and protest organizers mobilizing around economic grievances, IMF austerity, or government failures will find their activities painted as terrorism. The definition’s inclusion of “compelling government action” and “disruption of essential services” provides ready pretexts.

Diaspora activists who advocate for accountability, document past atrocities, or support Tamil political rights risk prosecution under the law’s extraterritorial provisions. Like the Online Safety Act before it, anti-terrorism legislation extends the state’s reach to Sri Lankan citizens abroad, potentially criminalising advocacy and political activity carried out entirely outside Sri Lanka.

Not all diaspora activism is benign—some elements remain problematic—but the PSTA’s vague and expansive provisions will inevitably sweep up legitimate human rights advocacy alongside genuine security threats.

International Law and Empty Rhetoric

Sri Lanka is party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which establishes clear standards for counter-terrorism legislation:

Terrorism must be narrowly defined to prevent abuse

Detention requires prompt judicial review

Definitions must include cumulative elements: serious violent acts PLUS intent to terrorize or coerce

No administrative detention without judicial authorization

Robust protections for expression, assembly, and association

The PSTA violates every standard. Deliberately.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Counter-Terrorism has repeatedly advised that anti-terror laws must restrict terrorism to “trigger offenses”—specific acts of serious violence like bombings or armed attacks. The PSTA’s definition encompasses non-violent “disruption of electronic systems” and “serious obstruction of essential services.”

International standards require cumulative intent: Both intent to cause serious harm and intent to intimidate or coerce. The PSTA requires only one of four possible intents, none of which need involve violence.

The International Commission of Jurists stated unequivocally in 2022: “The PTA cannot be reformed; it must be repealed.” The same logic applies to the PSTA. Laws built on frameworks of abuse cannot be salvaged through cosmetic adjustments.

Yet the government presents its draft as “rights-focused” reform. The PSTA’s preamble invokes Sri Lanka’s commitment to the rule of law and respect for fundamental rights. But, as legal experts have observed, “the contradiction could not be starker, despite a superficial attempt to ‘balance’ civil liberties through a revised preamble.”

Preambles protect no one. Operational clauses do. And the PSTA’s operational clauses enable systematic abuse.

The Path Not Taken: Alternatives to Repression

The government’s central justification—that some counter-terrorism framework is necessary—deserves examination.

Is it true that democratic nations require special terrorism laws suspending ordinary due process and rights protections?

No.

Many democracies handle terrorism through ordinary criminal law, prosecuting acts like murder, assault, conspiracy, and weapons offenses through normal courts with standard procedures. Canada explicitly treats terrorists as ordinary criminals, noting this “removes the political element and dilutes the effectiveness of the terrorist act” by denying extremists special status.

Where specific terrorism provisions exist—like in Germany or France—they remain integrated into the regular criminal code with full rights protections. Specialized investigative techniques or enhanced sentences, yes. Parallel legal systems with reduced rights protections, no.

Norway, after suffering one of history’s deadliest terror attacks (the 2011 Oslo bombing and Utøya massacre), consciously chose not to enact sweeping anti-terror legislation. Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg declared: “We will confront this terror with more democracy, more openness and more humanity.” Norway has remained both secure and rights-respecting without draconian laws.

The pattern is clear: established democracies with strong institutions, independent judiciaries, and genuine accountability can handle terrorism threats without suspending fundamental rights. They manage because they trust their justice systems to function even in difficult cases.

Sri Lanka’s rush to preserve PTA-style powers suggests lack of that trust—lack of confidence in police to investigate professionally, prosecutors to build cases on evidence, and courts to reach just conclusions through normal procedures.

The PSTA is a confession of institutional failure, packaged as security necessity.

What's Actually At Stake

The PSTA's very title reveals its orientation: "Protection of the State from Terrorism." Not protection of citizens. Not protection of democracy. Protection of the State—as if the State were some entity separate from and superior to its people, deserving protection from them.

This is authoritarian logic masquerading as security policy. In democracies, states exist to protect citizens, not the other way around. Laws should protect people from violence, not protect governments from criticism, dissent, or accountability demands.

The NPP government stands at a crossroads that will define its legacy. It can listen to civil society, legal experts, and minority communities. It can make substantial revisions that genuinely break from the PTA's oppressive legacy and demonstrate that "system change" actually means something. It can prove that a party born from resistance to state terror understands why such powers must never be normalized.

Or it can ignore these warnings, dismiss criticism as obstructionism, rely on parliamentary majorities to ram through repressive legislation, and prove itself just another iteration of Sri Lankan political cynicism—leaders who remember oppression only until they hold the power to oppress.

The choice will reveal whether the NPP's rhetoric about rights-focused governance was genuine principle or mere political expedience. History is watching. And history, as the JVP knows better than most, does not forget.