The Ritual of Self-Defeat

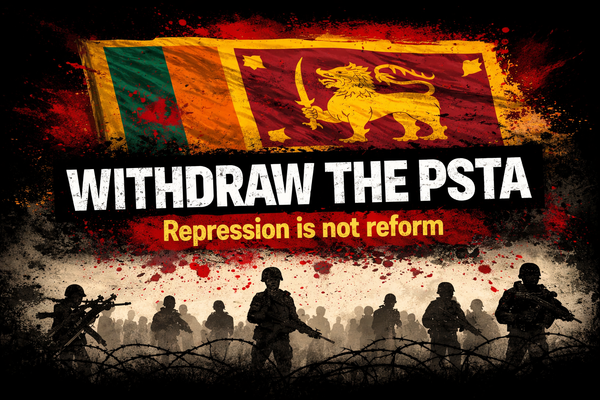

Once again, on February 4th, as Sri Lanka marked its 78th year of independence from British rule, a familiar theatre of political spectacle unfolded across the North and East. Black flags were hoisted. Placards were raised. Slogans denouncing the Sri Lankan state echoed through the streets of Kilinochchi, Batticaloa, and Jaffna. Tamil political figures — some elected, others self-appointed — declared the day a “Black Day,” a day of mourning and defiance.

To the uninitiated observer, the imagery may have appeared powerful. But to those who have watched this ritual evolve over the past two years, it is evident that the political theatre has not merely persisted — it has intensified. What began as symbolic protest has become a full-fledged annual mobilisation.

This year, in particular, the rhetoric was sharper and the staging more deliberate. Tamil nationalist leaders appear to have made a calculated bet: that the current government, desperate to court ultra-nationalist Tamil votes, will look the other way. And they are right. The NPP administration, caught between its rhetoric of national unity and its electoral arithmetic in the North, has chosen silence. The result is a perverse incentive loop: the government’s inaction emboldens the theatre, and the theatre, in turn, undermines the very political space the government claims to be building.

One thing, however, is clear: history teaches us that symbolic politics can carry profound and often unintended consequences. The Vaddukoddai Resolution of 1976, adopted amid rising frustration and political recalibration following the electoral setbacks of Tamil leadership, reshaped the trajectory of Tamil politics for decades.

What had once been a marginal slogan — the call for Tamil Eelam — was elevated into a formal political demand. It electrified a generation. But it also narrowed the boundaries of acceptable political discourse. Positions hardened. Moderation became suspect. Constitutional negotiation was delegitimised, replaced by absolutist rhetoric.

Political gestures made for short-term mobilisation can, over time, radicalise sections of youth in ways that offer no return — foreclosing compromise, dialogue, and political flexibility.

The tragedy is that history does not end where slogans begin. Leaders who help unleash uncompromising movements rarely control where those movements ultimately go. The assassination of A. Amirthalingam in 1989 by the LTTE, which deemed him insufficiently committed to its cause, stands as a grim reminder that radicalisation does not respect pedigree or past loyalty. Even early LTTE leaders themselves acknowledged that their political consciousness was shaped in the aftermath of the Vaddukoddai Resolution.

History issues a clear warning: political escalation, once normalised, carries consequences far beyond the immediate applause of the moment. This is not a five-minute spectacle. It is a generational gamble.

Yet the result of these annual performances remains the same: a predictable, self-defeating ritual that yields no tangible gains for ordinary Tamils, while simultaneously furnishing Sinhala hardliners with fresh material to reinforce their long-standing claim that reconciliation is impossible with Tamils.

This editorial is not an apology for the Sri Lankan state’s well-documented crimes against the Tamil people. It is not a denial of the systematic discrimination, the pogroms of 1956, 1958, 1977, and 1983, the three decades of devastating war, the mass atrocities of Mullivaikkal, or the continuing injustices of military occupation, enforced disappearances, and land appropriation in the North and East. Every Tamil carries the weight of this history. Every Tamil has earned the right to demand justice.

But there is a vast and consequential difference between demanding justice and performing grievance. There is a chasm between fighting for rights within the democratic framework of a nation you belong to and ritually disowning that nation in a manner that achieves nothing — except to further marginalise the very people you claim to represent.

The Inconvenient History: Tamil Leaders Did Not Oppose Independence

The foundational premise of the “Black Day” narrative — that February 4, 1948, was a catastrophe inflicted upon the Tamil people — crumbles under the most basic historical scrutiny.

Ceylon’s independence was not seized through bloodshed. It was not the culmination of a revolutionary war. It was a negotiated, constitutional transfer of power from the British Crown to a Ceylonese government, achieved through the Soulbury Commission process and formalised by the Ceylon Independence Act of 1947 in the British Parliament. The transition was peaceful, orderly, and — this is the critical fact — actively facilitated by Tamil political leadership.

Gajendrakumar Ponnambalam, today the torchbearer of the so-called Black Day protest, stands in striking contrast to his own political lineage. His grandfather, G. G. Ponnambalam — then the most prominent Tamil political leader in the country and founder of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress — did not oppose independence.

On the contrary, following the 1947 parliamentary elections, in which the ACTC won seven of the nine seats in the Northern Province, G. G. Ponnambalam participated in the Yamuna Conference, an attempt to form a post-independence government. When those negotiations failed, he did not boycott the new state. He did not declare independence a “Black Day.”

Instead, in September 1948 — barely seven months after independence — Ponnambalam joined the cabinet of Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake as Minister of Industries, Industrial Research, and Fisheries. He accepted a cabinet portfolio in the very government of independent Ceylon.

Nor was G. G. Ponnambalam alone in choosing engagement over rejection. Arunachalam Mahadeva, who contested the 1947 parliamentary election in Jaffna and lost to Ponnambalam, nevertheless chose to work with the first government and was later appointed Sri Lanka’s first High Commissioner to India. In Mannar, C. Sittampalam, who won the 1947 election as an independent candidate, was appointed Minister of Posts and Telecommunications. C. Suntharalingam — often credited as one of the earliest voices to articulate the idea that would later evolve into the Tamil Eelam demand — was appointed Minister of Trade and Commerce after winning independently in Vavuniya and extending support to the UNP-led government.

Tamil leaders were not merely present at independence; they were participants in shaping the new state. Of the 18 members in Sri Lanka’s first cabinet, three were Jaffna Tamils.

Even S. J. V. Chelvanayakam — who later broke with Ponnambalam in 1949 to form the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi over serious disagreements, particularly concerning the disenfranchisement of Indian Tamils — did not call for the rejection of Sri Lankan statehood itself. Chelvanayakam’s demand was federalism: a restructuring of the state, not its disavowal. The very name “Federal Party” was a declaration that Tamils sought autonomy within Ceylon — not separation from it.

The “Black Day” narrative is therefore not a continuation of a long-standing Tamil political tradition. It is a modern fabrication, a retroactive rewriting of history to serve the purposes of a political class that has run out of ideas and has nothing left to offer except the theatre of perpetual victimhood.

The Bloodless Independence We Squandered

There is a deeper historical irony that the “Black Day” advocates wilfully ignore. Sri Lanka’s independence was achieved without bloodshed. Unlike India, where the independence movement involved decades of mass agitation, imprisonments, and the trauma of Partition, Ceylon’s transition was constitutional and peaceful. Unlike Algeria, where independence from France was purchased with the blood of over a million people, Ceylon negotiated its way to sovereignty through commissions, constitutional drafts, and parliamentary acts.

The Soulbury Constitution, for all its limitations, contained Section 29(2) — a provision that explicitly prohibited Parliament from enacting legislation that discriminated against any religious or communal community. Combined with the constitution’s two-thirds amendment requirement, this created a structural safeguard for Tamils and other minorities. It was neither perfect nor sufficient — the Sinhala Only Act of 1956 would later pass without triggering constitutional invalidation, exposing the clause’s lack of justiciability. But it represented a constitutional starting point, a foundation upon which Tamil political leaders could have built a progressively more equitable state.

What happened instead? The minority protections were systematically dismantled — not only because of Sinhala majoritarian assertiveness, but also because Tamil political strategy lacked coherence and institutional durability.

G. G. Ponnambalam’s shift from demanding 50-50 representation — a formula that, however impractical, had at least asserted Tamil political weight — to joining the cabinet fractured Tamil unity, prompting S. J. V. Chelvanayakam to break away and form the Federal Party in 1949. The Federal Party alternated between satyagraha campaigns and electoral pacts with Sinhalese leaders — the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact of 1957, the Dudley-Chelvanayakam Pact of 1965 — both of which were abrogated under Sinhala nationalist pressure. Neither approach built the sustained institutional power needed to protect Tamil interests within the state.

As constitutional space narrowed and political trust collapsed, a generation of Tamil youth — disillusioned by both the state and their own leadership — turned toward militancy, setting in motion a conflict that would devastate the community for three decades.

The “Black Day” protests are, in this sense, the latest chapter in a long history of Tamil political leadership failing the Tamil people through an inability to articulate and execute a realistic, sustainable strategy for securing Tamil rights within the Sri Lankan polity.

The Paradox of the Oath

Tamil MPs who participated in the “Black Day” protests declared that they reject all political solutions under a unitary state constitution. Yet each of them has sworn an oath in Parliament to uphold and defend that very Constitution — which clearly defines Sri Lanka as a unitary state.

The Sixth Amendment to the Constitution — enacted in 1983 in the immediate aftermath of Black July — requires all members of Parliament, and indeed all holders of public office, to swear an oath renouncing separatism. The framework is designed precisely to criminalise or disable secessionist advocacy within formal politics. It has historically reshaped Tamil parliamentary participation, creating a structural tension for any elected representative who publicly commits to objectives that fall outside the constitutional order they have sworn to uphold.

One cannot swear to defend a constitutional order while publicly rejecting its foundational structure. If these MPs truly believe no solution is possible within the unitary framework, then their continued participation in Parliament raises serious questions. Are they working to reform the system from within? Or are they rejecting it outright while benefiting from its privileges?

The predictable effect is that symbolic secessionist signalling becomes politically inexpensive as street theatre but institutionally expensive in practice: it invites surveillance, proscription logic, and legal vulnerability while doing nothing to advance implementable reforms such as devolution, language parity, or administrative demilitarisation.

Political rhetoric may mobilise crowds. Constitutional inconsistency, however, weakens credibility — and credibility is the one currency Tamil politics cannot afford to squander.

Why Symbolic Estrangement Weakens Tamil Leverage Inside the State

The strongest practical critique of Black Day politics is not moral. It is institutional.

Sri Lanka’s constitutional order — however contested — is the arena in which day-to-day governance decisions are made: land administration, policing powers, language implementation, provincial resources, education systems, local economic policy, and the legal mechanisms needed for accountability and reparations. Reforms must be pursued through constitutional and political processes if they are to become enforceable realities.

Equally important is the international constraint. Every major UN human-rights resolution on Sri Lanka has reaffirmed the country’s “sovereignty, independence, unity and territorial integrity,” even while pressing for reconciliation, accountability, and human-rights protections. That is not a rhetorical flourish — it signals the outer boundary of what the international system is willing to endorse in practice.

India — a decisive external actor in Sri Lanka’s devolution architecture — has repeatedly articulated a two-track position: support for Tamil equality and dignity within Sri Lanka’s unity and territorial integrity, alongside calls for implementation of devolution provisions. Whether one agrees with India’s approach or not, it is a hard geopolitical reality that shapes the feasible menu of outcomes.

If Tamil politics signals, year after year, that the state itself is illegitimate, the likely result is not increased international appetite for state partition. The more predictable result is a tightening of the security narrative, reduced Sinhala political space for compromise, and a weakening of cross-ethnic alliances needed for constitutional change.

Research on political commemorations and protest mobilisation is clear that public rituals can consolidate group boundaries and harden political identities — especially when repeated on a fixed calendar and tied to emotionally charged narratives of collective suffering. In a post-war environment where policy leverage depends on coalition-building, constitutional negotiation, and credible claims-making inside legal institutions, an annual ritual that communicates estrangement from the state carries predictable strategic costs — no matter how morally understandable the grief behind it may be.

The Cost of Eternal Rejection: A Demographic Catastrophe

The advocates of the “Black Day” narrative never address the most devastating consequence of the politics they promote: the continuing demographic erosion of the Tamil community in Sri Lanka.

Consider the facts. Jaffna district had a population of 701,600 in 1971. By the 2012 census, it had fallen to 583,400. Preliminary results from the 2024 census place the figure at 594,333 — some post-war recovery, but still not a return to the earlier baseline, more than half a century later. The thirty-year war claimed the lives of an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 people. UN analysis of the war’s final phase noted that credible sources estimated as many as 40,000 civilian deaths in that period alone. For the Tamil people, the war effectively erased close to ten per cent of their population. In a small nation, that is a demographic catastrophe of staggering proportions.

And what has the politics of rejection delivered since? Has the annual “Black Day” protest brought back a single disappeared person? Has it secured the release of a single political prisoner? Has it returned a single acre of occupied land? Has it rebuilt a single school, hospital, or road in the war-devastated North?

The answer, after years of black flags and fiery rhetoric, is nothing. Absolutely nothing. The only measurable outcome of the politics of perpetual rejection is the continued exodus of Tamil youth from the North and East — young people who see no future in a homeland whose political class offers them nothing but the recycled grievances of the past.

Every young Tamil who leaves Sri Lanka because they see no path forward is another victory for those who sought to depopulate the Tamil homeland. The separatist politicians who wave black flags on February 4th and then return to their comfortable lives in Colombo are, in effect, accomplices to this demographic destruction. They offer no economic programme, no development vision, no educational strategy. They offer only anger — and anger, however justified, cannot feed a family, educate a child, or rebuild a nation.

Post-war socio-economic pressures compound the strategic vulnerability. Northern provincial indicators show substantial poverty and unemployment, with district-level data reflecting ongoing economic fragility. In post-conflict settings globally, such vulnerabilities are repeatedly identified as risk multipliers when combined with political exclusion and unresolved trauma. Against this backdrop, an annual ritual that primarily generates symbolic heat is not “free.” Its opportunity cost is the diversion of scarce organisational capacity away from policy campaigns that can alter budgets, administrative decisions, court outcomes, and constitutional reform.

How “Black Day” Politics Can Radicalise Another Generation

The fear that ritualised rejection can radicalise youth is not speculative. It is consistent with both Sri Lanka’s past trajectory and comparative research on how grievance, exclusion, and identity-based mobilisation interact.

Sri Lankan scholarship on youth radicalisation emphasises that Tamil youth mobilisation historically escalated when political bargaining repeatedly failed, when discrimination shaped access to education and employment, and when confrontational state tactics met constitutional demands with repression. The mechanism is cumulative: frustrated reformist politics leads to loss of faith in democratic redress, which in turn creates attraction to extra-parliamentary methods.

Ritual politics intensifies this risk by socialising young people into a worldview where the state is not a site of contestation but an object of permanent negation. That worldview is emotionally coherent — especially when grief and injustice are real — but it is politically corrosive because it teaches that participation is either betrayal or uselessness.

It is also crucial to acknowledge the diaspora dimension. Major conflict-analysis reports on the Tamil diaspora describe how diaspora networks shaped the political landscape through financial and ideological support over decades — an influence that does not vanish simply because the war ended. None of this implies that diaspora engagement is inherently harmful; it does mean that diaspora incentives can diverge from the day-to-day survival priorities of those living in the North and East.

The Diaspora Factor: Funding Division from a Distance

No honest assessment of the “Black Day” phenomenon can ignore the role of the Tamil diaspora. The protests that unfold annually in Kilinochchi, Batticaloa, and Jaffna do not materialise spontaneously from grassroots anger. They are organised, funded, and amplified by diaspora networks — organisations based in London, Toronto, Sydney, and other Western capitals where Tamils who left Sri Lanka decades ago continue to pursue political agendas disconnected from the daily realities of Tamils who actually live in the North and East.

Diaspora organisations raise millions in the name of Tamil rights, sustain political movements they control from thousands of miles away, and maintain an industry of activism that depends, fundamentally, on the continuation of Tamil suffering. Their political relevance — and their fundraising capacity — requires that the Tamil question remain unresolved. A Tamil community that is thriving, integrated, and advancing within Sri Lanka is, paradoxically, a threat to the diaspora political establishment that profits from Tamil misery.

This is not to suggest that all diaspora Tamils are cynical operators. Many are genuinely traumatised survivors of the war who carry legitimate wounds and authentic grief. But the organisations that channel their emotions into political action have a structural incentive to perpetuate conflict rather than resolve it. The “Black Day” protests are the perfect vehicle: annual rituals of rage that produce spectacular imagery for social media, generate donations from emotionally charged audiences abroad, and deliver precisely nothing for the Tamil mother in Mullaitivu who simply wants to know what happened to her son.

What Would a Constructive Tamil Politics Look Like?

Rejecting Black Day politics does not require forgetting state crimes or abandoning justice. It requires choosing a strategy that can actually scale into enforceable outcomes.

A constructive Tamil politics would begin with a clear-eyed acceptance of the fundamental reality: Sri Lanka is our homeland, and there is no viable alternative to securing our rights within it. The armed struggle is over. The dream of a separate state died at Mullivaikkal. The international community, whatever its sympathies, will not partition Sri Lanka. These are not opinions. They are facts.

First, the constitutional path is not imaginary. Devolution under the Thirteenth Amendment exists as an institutional framework, rooted in the Indo–Sri Lanka Accord and continuously invoked in diplomacy and domestic debate as the baseline for power-sharing. Whether one sees it as insufficient or compromised, it is presently the most recognised constitutional mechanism for sub-national autonomy on the island. A serious Tamil political movement would demand its full implementation and push for its expansion.

Second, international accountability and transitional justice mechanisms — however incomplete — are pursued through institutions, not symbolism. UN human-rights processes, OHCHR documentation work, and domestic mechanisms such as the Office on Missing Persons are contested, slow, and often frustrating, but they represent the practical channels through which evidence is gathered, cases are tracked, reparations are debated, and international pressure is sustained.

Third, a serious Tamil politics would build alliances with progressive forces across ethnic lines — Sinhalese, Muslim, and Tamil — who share a common interest in democratic governance, human rights, and the rule of law. Cross-ethnic legislative coalitions are the only realistic vehicle for constitutional reform in a country where Tamils constitute a permanent electoral minority.

Most importantly, constructive Tamil politics would invest in the economic and educational development of the Tamil community. It would prioritise infrastructure, employment, and educational opportunity over symbolism and sloganeering. It would work to stem the catastrophic brain drain that is emptying the North of its most talented young people. It would build the economic base that gives political demands real leverage — because a community that is economically vital to the nation cannot be marginalised as easily as one that is economically dependent. It would encourage the influential diaspora community to invest in the North and East, channeling resources into development rather than protest.

None of this is glamorous. None of it produces the dramatic imagery that fills social media feeds and loosens diaspora purse strings. But it is the only politics that has ever worked for any minority, anywhere in the world, at any point in history.

This Is Our Soil

I write this not as a dispassionate observer but as a Tamil — a Tamil who carries every wound, every scar, and every memory of injustice that our community has endured. I have not forgotten the disenfranchisement of Indian Tamils in 1948. I have not forgotten the Sinhala Only Act of 1956. I have not forgotten the burning of the Jaffna Public Library in 1981, the pogrom of July 1983, or the horrors of Mullivaikkal. I carry these memories not as abstractions but as the lived inheritance of a people who have been wronged, repeatedly and grievously, by the state they call home.

But I refuse — absolutely and categorically refuse — to let those memories become chains that bind my community to a politics of permanent defeat. The Tamil people did not survive five centuries of colonialism, three decades of war, and the attempted annihilation of their community only to be led into oblivion by politicians whose primary talent is the monetisation of grief.

Civic belonging is not a denial of Tamil nationhood as culture, language, or historical identity. It is a strategic insistence that the state must be refounded as a genuinely multi-ethnic democracy where Tamils can claim equal ownership. The alternative — performing permanent estrangement while expecting constitutional concessions — has repeatedly failed because it reduces bargaining power, fragments alliances, and offers the state an excuse to treat Tamil politics as a security problem rather than a governance problem.

Sri Lanka’s past contains injustice. That truth cannot be erased. But the future cannot be built on permanent symbolic separation from the state. For Sri Lankan Tamils, the strategic question is not whether the Republic has failed them before. It has. The question is whether they will abandon the project of reshaping it — or claim it as their own.

Rejecting Independence Day may feel like resistance. Reclaiming the state and demanding that it serve all citizens is a far more radical act.

The challenge for Tamil politics today is not how loudly it can signal alienation. It is whether it can convert grievance into governance.