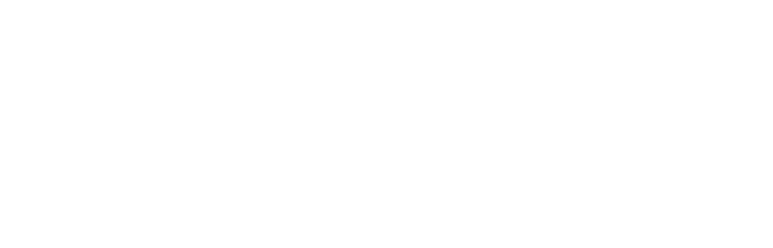

Sri Lankans awoke this week to a curious cocktail of relief and dread. On July 9, 2025, in a characteristically dramatic turn, U.S. President Donald Trump declared that the steep 44% tariff slapped on Sri Lankan exports would be trimmed to 30%.

Set to take effect on August 1, the reduction is part of Trump’s aggressive “reciprocal tariff” doctrine—his claim to level the playing field by matching the import taxes that other nations impose on American goods. While 30% is still a heavy blow, it’s a slight reprieve from what was one of the harshest trade penalties Sri Lanka had ever faced.

In his latest letter to President Anura Kumara Dissanayake—mistakenly addressed as “Aruna Kumara Dissanayake”—U.S. President Donald Trump confirmed that the new tariff rate will be 30%, down from the previously threatened 44%.

But make no mistake—30% is still a significant blow to Sri Lankan exporters. “Compared to the previous average tariff of just 6% on Sri Lankan goods, this is enormous,” said one economic expert. “Even at 30%, this rate could cripple competitiveness in key sectors like apparel and tea.”

And it doesn’t end there. Another trade analyst told Jaffna Monitor that the tariff reduction comes with strings attached. “The Sri Lankan government may now face pressure to offer trade concessions or even align politically in exchange for further relief,” he warned. “That makes the situation far more complicated than it appears on the surface.”

Trump’s letter bluntly framed the move as part of his push for “balanced and fair trade.” He complained that Sri Lanka’s tariffs and other trade barriers have led to persistent U.S. trade deficits, making the relationship “far from reciprocal.”

While some Sri Lankan ministers are boasting that the reduction is a result of their masterful negotiation skills, the truth appears far less flattering. In classic Trumpian style, the U.S. President warned Sri Lanka not to retaliate: “If for any reason you decide to raise your tariff, then whatever number you choose… will be added onto the 30% that we charge.”

He also bragged that “30% is far less than what is needed to eliminate the trade deficit disparity.”

For Sri Lanka, which was initially hit with a shocking 44% duty, being “spared” with 30% now feels like cold comfort—“akin to being grateful the hangman gave you a two-week reprieve,” a political professor joked to Jaffna Monitor.

How was the initial 44% even arrived at?

Trump's so-called "reciprocal tariff" wasn't based on any actual Sri Lankan tax rate. Instead, his team took the U.S.-Sri Lanka trade deficit—$2.6 billion in 2024—and applied a simplistic and controversial formula: the ratio of the deficit to Sri Lanka's total exports to the U.S.

By that math, they calculated that the trade deficit of $2.6 billion represented roughly 88% of Sri Lanka's total exports to the U.S., which stood at $3.0 billion. They then imposed a 44% tariff—half of that 88% figure—as a so-called "discounted reciprocal tax."

This method has little to do with the actual tariffs Sri Lanka imposes on U.S. goods. In reality, Sri Lanka's applied tariff rates on U.S. goods average around 8.84% for all products, according to World Bank data based on WTO statistics. Sri Lanka operates a simplified three-tier tariff structure with rates of 0%, 10%, and 15% depending on the product category.

Nevertheless, Trump has used the narrative that "Sri Lanka is charging 88% in taxes and trade barriers" on American products as political justification to impose aggressive tariffs under his broader "America First" trade policy.

Sri Lanka’s Economic Disadvantages Under a 30% Tariff

For Sri Lanka, even a 30% U.S. tariff spells serious trouble, economists told Jaffna Monitor. The United States remains Sri Lanka's largest export market, accounting for roughly 24% of Sri Lanka's total merchandise exports—about $3 billion in 2024. The vast majority of these are textiles and apparel, followed by rubber products and tea and agricultural goods. In other words, Sri Lanka's economic lifeline is now subject to a steep tax at the U.S. border.

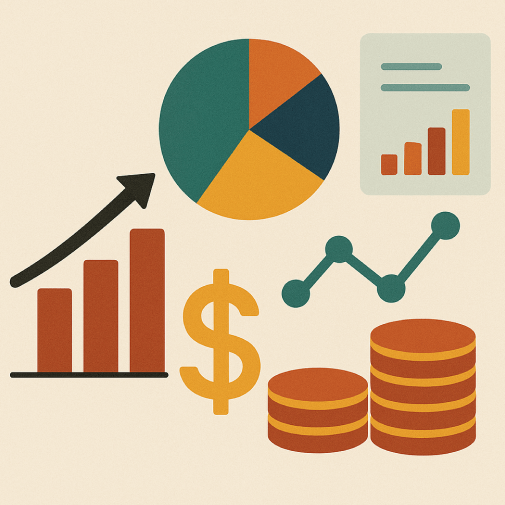

Exporters Lose Their Edge — and Orders

A 30% tariff can wipe out the price competitiveness of Sri Lankan goods almost overnight. For example, garments made in Sri Lanka will now become significantly more expensive for U.S. retailers. Competing countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam, and even India—which face lower U.S. tariffs—are likely to capitalize.

“They are waiting to take the share that breaks off from us, just like how South Asia once waited to take what was leaving China,” warned Dhammika Fernando, Chairman of the Free Trade Zone Manufacturers Association (FTZMA).

Sri Lanka could quickly lose U.S. market share to countries with more favorable terms. Yohan Lawrence, Secretary-General of the Joint Apparel Association Forum, told Reuters that the situation is “serious, and it must be addressed as a matter of national urgency.” With around 40% of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports destined for the U.S., buyers may simply pivot to sourcing from Vietnam or India, where new U.S. duties stand at 20% and 25% respectively—still high, but notably less than 30%.

The U.S. market absorbs nearly half of all Sri Lankan apparel exports—meaning any shock to this sector has broad implications for the economy and workforce, economic experts say.

Pressure on Prices and Jobs

Sri Lankan exporters, especially in apparel, which employs about 300,000 workers, are bracing for painful adjustments. To retain U.S. orders, many may be forced to slash prices—and profits—to remain competitive. Smaller suppliers operating on thin margins could be pushed out of the supply chain altogether if buyers demand deeper discounts.

There is already anecdotal evidence of distress. In April, workers at the Vogue Tex garment factory in southern Sri Lanka staged a protest after management withheld Sinhala-Tamil New Year bonuses, citing the looming U.S. tariffs as the reason. The company even temporarily shut down operations during that period. For the mostly female workforce, losing even a modest annual bonus was a severe emotional and financial blow.

Jobs, Wages, and Livelihoods at Risk

If exports fall, production will scale back and inevitably jobs will be lost. The FTZ Manufacturers Association estimates up to 50,000 jobs could be lost in the initial stages of the tariff impact. These would mostly be garment factory jobs – the kind held by rural women who are often the main earners in their families. Job losses on that scale are not just numbers; that’s 50,000 households potentially losing income.

Even workers who keep their jobs might see overtime hours cut and bonuses canceled, which translates to lower take-home pay. The ripple effect extends further: reduced income means lower spending in local economies, affecting everyone from grocery shop owners in Gampaha to tuk-tuk drivers in Katunayake. Sri Lanka is still recovering from its recent financial crisis, and unemployment or wage cuts in a major sector will add pressure to a population already grappling with high inflation.

It's worth noting that apparel is Sri Lanka's largest merchandise export earner and third-largest overall foreign exchange earner, after worker remittances and tourism—so any contraction in this sector strikes at the heart of the country's ability to earn dollars.

If garment factories begin shedding workers or shutting down, the social consequences could be severe. A recent example highlights the fragility of the sector: in May 2025, Next Manufacturing, a major British-owned garment factory, abruptly shut down citing "high operating costs," leaving approximately 1,400 Sri Lankans jobless. Workers were notified via WhatsApp messages after returning home, arriving the next day to find factory gates locked.

Pressure on the Sri Lankan Rupee and Trade Balance

Less export revenue means fewer dollars flowing into Sri Lanka, which could put downward pressure on the rupee. The trade deficit may widen if exports to the U.S. plunge while imports don’t adjust. Sri Lanka had a $2.6 billion trade surplus with the U.S. in 2024, which Trump sees as a problem for America – but that surplus is a crucial source of hard currency for Sri Lankans. Any dent in it will make it harder for Sri Lanka to balance its overall trade. In the longer run, a weaker currency could make our other exports more price-competitive globally, but that’s small consolation if one of our top markets is effectively walled off by tariffs.

There’s also a confidence factor: Sri Lanka’s economy only recently stabilized after defaulting on external debt in 2022. Export recovery was one bright spot. Now, the tariff shock introduces new uncertainty. Currency markets and investors hate uncertainty. In fact, after Trump’s tariff plans were first announced in April, Sri Lanka’s international bonds slid by as much as 2.5 cents on the dollar amid a broader selloff in frontier markets. Investors saw the tariffs as a threat to Sri Lanka’s comeback story. A sustained hit to export earnings could make it harder for Sri Lanka to rebuild its foreign reserves and could even complicate our ongoing IMF program. The IMF itself voiced concern, noting that external shocks like these tariffs create uncertainty for the recovery path. If export industries suffer, foreign investors may put plans on hold and Sri Lanka’s risk profile could worsen, making it costlier to borrow money abroad.

By the Numbers: Potential GDP and Job Loss Scenarios

How bad could the damage be—economically and socially? While precise forecasting is difficult, experts are beginning to sketch some worrying possibilities.

Export Revenue Loss

Sri Lanka earned about $1.9 billion from apparel exports to the U.S. last year. With a 30% tariff in place, a large portion of that business could become unprofitable.

Some analysts predict Sri Lanka could lose $500–600 million in export earnings if U.S. orders fall sharply.

To put that in context:

- That loss alone is equal to roughly 0.8% of Sri Lanka’s GDP.

- While not catastrophic, it could still shave off a full percentage point from annual growth if not compensated by gains elsewhere.

- And that’s just apparel. Exporters of rubber products, tea, spices, and other goods will also feel the pinch.

Jobs at Stake

Estimates suggest that up to 50,000 jobs could be at risk. That’s one in every six jobs in the apparel sector, which directly employs about 300,000 Sri Lankans—most of them women. For thousands of families, this would mean a loss of income, increased household debt, and rising economic insecurity, especially in rural and semi-urban areas where many garment factories are located.

Growth Slowdown

Sri Lanka posted 5% GDP growth last year as the country slowly climbed out of its economic crisis. But the U.S. tariff shock could weigh heavily on that recovery.

If export factories scale down operations or shut down, economists estimate that GDP growth in 2025 could slow by 0.5% to 1%.

And the damage doesn’t stop there. There’s a multiplier effect:

- Every dollar lost in exports means less spending and less investment at home.

- The Central Bank may have to revise its forecasts downward.

- And government tax revenues—already under strain—could fall further if corporate profits and wages decline in the export sector.

Navigating the Storm: What Sri Lanka Must Do Now

The U.S. tariff shock may have caught us off guard—but it shouldn't paralyze us," an economist told Jaffna Monitor. He continued, "This is a wake-up call, not a death sentence". Here’s how Sri Lanka can fight back, adapt, and come out stronger.

Time to Stop Putting All Our Eggs in One Basket

Let’s face it—depending on the U.S. for 40% of our apparel exports was always a gamble. Now that the gamble has backfired, we need to urgently pivot to other markets.

Sri Lanka should double down on the UK, EU, Japan, and even regional giants like India and China. We already enjoy GSP+ preferential access to the EU, which lowers tariffs on many of our products—keeping that status intact is critical.

Export promotion agencies must now go on the offensive—helping manufacturers attend trade expos, build contacts, and market their products abroad. Even within apparel, Sri Lanka can aim for premium niches in Europe or Asia—sportswear, designer labels, sustainable fashion.

Experts say market diversification won’t happen overnight. But even reducing U.S. reliance by 5–10% over the next year would help soften the blow. It’s time we stop being a one-market story.

Diversify and Upgrade Products

Sri Lanka needs to move up the value chain. That means producing sportswear, technical textiles, lingerie, and other higher-value goods instead of just bulk basics. Beyond apparel, we could shift from exporting raw rubber to manufacturing finished rubber products, and from selling bulk tea leaves to marketing branded tea drinks. If Sri Lankan goods are known for innovation and quality, some buyers might stick with us even despite the tariffs," opined an exporter.

That said, government support is essential. The government must offer incentives for R&D, innovation, and branding. It should also encourage technology partnerships and support local designers in building globally recognized Sri Lankan labels.

Reduce Sri Lanka’s Own Import Barriers: Address the Elephant in the Room

Trump’s claim that 'Sri Lanka is taxing U.S. goods unfairly' might be exaggerated—but it’s not entirely false. We do slap hefty tariffs on imports, especially electronics, where duties can exceed 80%. But when it comes to vehicles, Sri Lanka—ironically branded the 'Wonder of Asia'—performs its real magic trick: pulling off mind-bending tariffs that range from 400% to 600%.

To put it in perspective: if someone imports a $20,000 American car, they could end up paying $80,000 to $120,000 in taxes alone. The final cost? Anywhere from $100,000 to $140,000—for a car that originally cost just $20,000. 'It’s stupid-crazy,' said one frustrated vehicle importer."

So what would a smart approach look like? 'The government should announce targeted tariff cuts on items like U.S. machinery, auto parts, or agricultural goods—things that don’t hurt local producers but benefit consumers and businesses,' an expert explained to Jaffna Monitor.

'This would help undercut Trump’s “reciprocal tax” justification, lower production costs for local industries, and send a message of goodwill—without appearing to beg. Though technically, yes, it's still a bit of begging,' he joked.

Fairer trade goes both ways. 'If we show a willingness to open up even slightly, Washington might reconsider the severity of its tariffs. Plus, lower import duties tend to attract investment—foreign companies are far more likely to set up operations if their inputs come in cheaper,' he added.

Don’t Stand Alone

The global economy is increasingly driven by trade blocs—and Sri Lanka can’t afford to watch from the sidelines. We’ve already expressed interest in joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a mega-trade pact that includes China, Japan, ASEAN, Australia, and others. Fast-tracking our entry could open doors to massive new markets and more predictable trade frameworks.

Regionally, SAARC may be stuck in diplomatic quicksand, but India still matters—a lot. “We should be exploring joint production chains with India, especially in apparel,” said Rajkumar, a seasoned trader. “Imagine garments being assembled across borders to qualify for preferential rates in third-party markets. It’s doable.”

Turning Crisis into Opportunity?

The coming months will test Sri Lanka’s agility. Can we find new markets for our goods? Can we innovate and climb the value ladder so that “Made in Sri Lanka” stands for more than just cheap needlework?

There is room for cautious optimism. Sri Lanka’s export community has weathered adversity before—from the end of a long civil war to losing and later regaining EU trade preferences—and each time, it adapted. This time, adaptation might mean a pivot eastward: more of our tea heading to China, more apparel to Japan. Or it may mean reinvention—like the tech sector stepping up exports or agriculture shifting to higher-value products.

The tariff fight is also pushing overdue reforms. If it accelerates the removal of archaic import taxes and bureaucratic trade barriers, Sri Lanka could become far more competitive in the global market.

Island nations like Sri Lanka must remain agile in an era dominated by big-power trade rivalries. Trump’s tariff salvo is a stark reminder that in global commerce, even friends can throw punches. The challenge before us is clear: absorb the blow, protect our most vulnerable sectors, and stay standing.

If we can turn this crisis into a springboard for diversification and reform, the tariff shock of 2025 might one day—perhaps in the eyes of a future generation—be remembered as the beginning of Sri Lanka’s economic renaissance. But making that leap demands more than resilience. It requires economic intelligence, visionary leadership, openness to the world, and strategic international partnerships.

Ironically, the very kind of global economic engagement Sri Lanka now urgently needs was once the target of fiery JVP rhetoric—back when the party was shouting from the streets rather than speaking from cabinet seats. Whether today’s leadership can rise to the occasion with clarity, credibility, and a coherent plan will determine the future that awaits all Sri Lankans.