The usually bustling streets of Colombo took on a distinctly vibrant hue late last month, as over 10,000 members of the Dawoodi Bohra community from around the world descended on the city for a week-long spiritual convention. Held from June 27 to July 5, the gathering coincided with the global Ashara Mubaraka sermons led by the community’s spiritual leader, Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin, in Chennai, India.

The Colombo leg of the event, held primarily at the Sri Lanka Exhibition and Convention Centre (SLECC) in Fort and the Bohra Mosque on Glen Aber Place in Bambalapitiya, brought an unmistakable energy to the capital. Security was visibly tight—especially following the arrest of a man identified as “Podi Saharan,” a known religious extremist.

Hardline Sunni extremists have historically branded the Dawoodi Bohras—an esoteric subsect of Shia Islam—as apostates, due to their distinct spiritual practices and hierarchical leadership. Security officials told Jaffna Monitor that “Podi Saharan” was reportedly caught taking suspicious photographs at the Bohra convention venue.

From five-star establishments to mid-range and budget lodgings, nearly every room in the city was booked. “It was like an invisible tourism season,” said one hotelier. Industry insiders estimate that the event generated several million US dollars in much-needed revenue for the country.

Historical Background: From Gujarat Shores to Ceylon’s Ports

The Dawoodi Bohras' presence in Sri Lanka began more by fate than by choice. In the early 19th century, a twist of destiny brought the first Dawoodi Bohra to the island’s shores. According to Bohra accounts, Jafferjee Essajee, a trader from Kutch in Gujarat, was shipwrecked during a storm in 1830 while en route to the Maldives and washed ashore in Galle.

Noting the presence of a sizeable Muslim population and recognising the island’s commercial potential, he seized the opportunity to establish a trading post in Galle. He began exporting Ceylonese rice to the Maldives and bartering for dried fish—a commodity that, according to some sources, was introduced to the Sri Lankan market by Bohra traders and later became a staple in local cuisine.

Impressed by the business prospects and social harmony, Essajee brought his family over and encouraged others from the community to follow. By the mid-1800s, a small but thriving Bohra community had taken root in Galle, complete with its own mosque: Jamali Masjid. Located on Old Matara Road, this mosque became the first Bohra masjid in Ceylon and still stands today.

When the British modernised Colombo’s port in the 1860s, many Dawoodi Bohras— sensing that Colombo was destined to become the island’s new commercial epicenter—relocated from Galle to the capital.

Religious Identity and Culture: Fatimid Legacy in a Modern Context

The Dawoodi Bohras trace their spiritual lineage to Tayyibi Isma'ilism, a distinct branch of Shia Islam that sets them apart from the Muslim mainstream in Sri Lanka. The community reveres a line of 21 Imams descended from the Prophet Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and son-in-law Ali—a lineage that once led the Fatimid Caliphate in Cairo. According to Bohra belief, the 21st Imam, al-Tayyib, went into sacred seclusion in the 12th century. Since then, spiritual authority has rested with the Dāʿī al-Muṭlaq—literally, the ‘unrestricted missionary’—who serves as the Imam’s vicegerent until his return. This institution, first rooted in Yemen and later established in India, continues unbroken to this day.

The institution of the Dai al-Mutlaq was first established in Yemen—legend credits the influential Queen Arwa al-Sulayhi with its formalisation—and was later relocated to India. To this day, the Bohra spiritual leader resides in Mumbai.

The current leader, Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin, is the 53rd Dai in an unbroken chain of succession. He also serves as the Chancellor of two of India’s most prominent universities: Aligarh Muslim University and Jamia Millia Islamia. Bohras worldwide—including those in Sri Lanka—swear allegiance to him as their supreme guide in both spiritual and temporal matters.

Global Leadership, Local Structure

In Sri Lanka, as in Bohra communities across the world, the Syedna appoints an Amil—a local representative tasked with overseeing both spiritual and administrative affairs. ‘All major religious decisions are ultimately referred to Syedna,’

Bohras follow a distinct religious calendar rooted in Fatimid tradition, worship in their own community mosques, and observe a unique approach to Friday prayers. According to doctrine, only the hidden Imam—or his appointed deputy, the Dāʿī al-Mutlaq (Syedna)—is considered qualified to deliver the formal khutbah (sermon). As a result, instead of the conventional Friday sermon, Bohra mosques around the world receive sermons and spiritual guidance relayed from Mumbai by the Syedna or his designated representatives.

“This centralized model—where pulpit authority is carefully regulated—may be one reason the Bohras have remained untouched by the extremist currents that have infiltrated some Sunni sects, where sermons are often decentralized,” noted an observer of Islamic studies in conversation with Jaffna Monitor.

To this day, the Bohras have largely remained immune to the extremist ideologies that have taken root in segments of the South Asian Muslim world—including in Sri Lanka—in recent decades.

“They prioritise spiritual elevation over rigid textualism,” explained a scholar familiar with Bohra theology. “Their focus is on confronting the inner kāfir—the nafs al-ammārah, or the commanding self that leads one toward doubt, denial, and ego—rather than waging war against external kāfirs, those who reject or disbelieve in Islam.”

A devoted Bohra put it more plainly:“We don’t go out to fight the external kāfirs. What’s the use of that, when you haven’t yet conquered the kāfir within yourself?”

Understanding the Sunni–Shia Split

To understand the Dawoodi Bohras and their place within the Islamic world, it’s helpful to briefly look back at how Islam branched into different sects following the death of Prophet Muhammad.

When the Prophet passed away in 632 CE, there was no explicit instruction on who should succeed him as leader of the Muslim community, an Islamic scholar explained to Jaffna Monitor. This ambiguity led to a profound division. One group—later known as the Sunnis—believed that leadership should be determined by consensus, and supported Abu Bakr, the Prophet’s close companion, as the first Caliph. For them, leadership was primarily a matter of political stewardship and communal choice.

Another group, however, believed that leadership should remain within the Prophet’s family, particularly with Ali ibn Abi Talib, his cousin and son-in-law. They held that the Prophet had designated Ali as his rightful spiritual and temporal successor. This group came to be known as the Shia, meaning “the party of Ali.”

What began as a political disagreement slowly evolved into deeper theological and spiritual differences over the centuries. Shia Muslims placed great emphasis on the divinely appointed lineage of leaders, or Imams, from Ali’s family, while Sunnis developed systems of law, scholarship, and leadership based on community consensus and traditions (Sunnah).

Among the many branches that later formed within Shia Islam, one was the Ismailis, and from them, the Dawoodi Bohras emerged.

Faith and Devotion: A Distinctive Blend

The Dawoodi Bohra faith is an esoteric blend of Shi’a Islam’s devotional traditions and a distinctly modernist outlook. “Bohras uphold the core tenets of Islam—belief in one God, the Prophet Muhammad, and the Quran—but interpret them through the lens of Fatimid-Tayyibi theology,” a Bohra scholar explained to Jaffna Monitor.

At the heart of their faith lies deep love and unwavering loyalty to the Prophet’s family (Ahl al-Bayt) and the line of Imams.

Discipline, Devotion, and the Strength of Community

Discipline and order are hallmarks of Dawoodi Bohra culture, explained a Colombo-based Bohra. “Guided by our spiritual leader, the Syedna, our global community runs a wide range of philanthropic initiatives rooted in Islamic values and Fatimid traditions.”

One standout example, he said, is the Faiz al-Mawaid al-Burhaniyah (FMB) program—a global community kitchen system. Every Bohra congregation, including Colombo’s, operates a centralized kitchen that delivers one free, freshly prepared meal daily to every Bohra household. “The aim was to relieve women from the daily burden of cooking, giving them more time for education, prayer, and family,” he noted.

The Colombo Jamaat’s kitchen, near Husaini Masjid in Bambalapitiya, prepares over 2,000 meals a day—delivered with precision by a team of volunteers.

Cleanliness, punctuality, and law-abiding behavior are deeply embedded in Bohra life,” said another community leader. “Our mosques and community centers are meticulously maintained—often spotless even after large events. You’ll never see litter after a Bohra gathering.”

He added that during major events, including international conventions, Bohra volunteers in uniform efficiently manage traffic, security, and crowd control—so well.

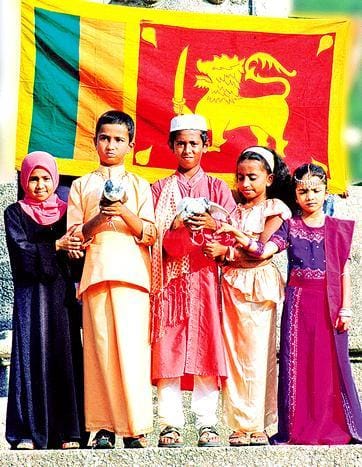

At the same time, the Bohras remain somewhat insular by design, a deliberate effort to preserve their centuries-old traditions in a rapidly changing world. Across the diaspora, they speak Lisan al-Dawat, a unique dialect of Gujarati infused with Arabic, Persian, and Urdu vocabulary, used both at home and in religious settings. Social life is largely community-based: Bohras typically marry within the faith, attend their own schools, and often prefer to enter into business partnerships with fellow community members.

Trading in the Blood: How Sri Lanka’s Dawoodi Bohras Quietly Shaped a Business Empire

“The word Bohra comes from the Gujarati vohrvu or vyavahar, meaning ‘to trade,’” said a successful Bohra businessman to Jaffna Monitor. “So yes, in a way, being a Bohra means being a trader—both literally and culturally. It’s not just vocabulary. It’s in our bones.”

For generations, the Dawoodi Bohras have been a community of merchants. Wherever in the world they settle—be it Sri Lanka, East Africa, the Gulf, or the West—they bring with them a legacy of commerce, discipline, and trust. “It’s like this,” he added. “If your father is a doctor and your grandfather was one too, chances are you’ll grow up in that world and excel at it. It’s the same with us. We’ve been in trade for centuries—not since yesterday. That long experience teaches you more than any MBA.”

And true to his words, much like the Parsis in India, the Dawoodi Bohras have played an outsized role in Sri Lanka’s commercial life. Despite numbering only around 2,000, they have stood at the forefront of trade and enterprise for nearly two centuries.

One of the pioneering families, the Hebtulabhoys, famously broke the British monopoly on tea exports in 1907, becoming early architects of what would become Sri Lanka’s most iconic export industry.

A charming account of this entrepreneurial spirit comes from Tudor Jones, a Welsh journalist and one-time editor of The Ceylon Times. Writing in the 1935 Times of Ceylon Christmas Number, Jones recalled:

“I was once looking for University College, Colombo, and drove into an impressively large building which I thought must be it. But I found that it was the residence of a Bohra—and University College was the meaner building next door.”

That legacy lives on through some of Sri Lanka's most successful enterprises. Akbar Brothers, founded in 1969, stands as Sri Lanka's largest tea exporter for over three decades, shipping more than 52 million kilograms annually and accounting for 16% of the country's total tea exports. The company has become a global leader, earning recognition as the world's largest Ceylon tea exporter while employing over 2,500 people.

The Esufally family, through the Hemas Group, has built one of Sri Lanka's most respected conglomerates, operating across healthcare, pharmaceuticals, consumer goods, and mobility sectors. With over 4,500 employees, Hemas has expanded beyond Sri Lanka to Bangladesh and other regional markets, establishing itself as a major force in South Asian business.

The Adamjee Lukmanjee Group, with roots stretching back to 1865, remains one of Sri Lanka's pioneering export houses. For over 160 years, the company has been a leading manufacturer and exporter of coconut products and spices, maintaining strong positions in agriculture and manufacturing while expanding into 60+ countries across six continents.

Collectively, Bohra-led businesses generate well over USD 600 million in annual revenue and provide direct and indirect employment to more than 12,000 Sri Lankans—all from a community numbering just around 2,000, a source told Jaffna Monitor.

“Our high priest, the Syedna, has always emphasized one thing in every sermon,” said a senior Bohra businessman. “‘Be fair in your business. Be honest in your business.’ He constantly reminds us that integrity, fairness, and transparency in commercial dealings are not just good practices—they are religious duties. And we Bohras have tried to live by that for generations.”

As we spoke to several leading Bohra entrepreneurs and other Bohras in Sri Lanka, a curious pattern emerged: while they were eager to share insights about their community’s business ethics and spiritual roots, they all—without exception—politely requested anonymity.

One of them explained why: “In our community, public representation is a sacred matter. It’s not just anyone who speaks for the Bohras. That responsibility belongs to Syedna and his designated representatives. Our leadership believes that the world should hear a consistent voice about who we are—not fragmented versions.”

Women of Grace and Grit: The Bohra Model of Empowerment

'Religious conservatism often walks hand-in-hand with the suppression of women—but the Dawoodi Bohras present a quiet yet striking exception, one that serves as a model not just for Muslim communities, but for all', explained Manoharan, a student of religious studies, to Jaffna Monitor.

“Long before it became commonplace in Sri Lanka’s broader Muslim society, Bohra women were already driving cars in Colombo in the 1960s and ’70s, managing homes and businesses with confidence,” he noted. “It’s a reflection of the community’s modernist ethos—firmly grounded in faith, but never chained by patriarchy.”

Today, Bohra women in Sri Lanka—and across the global diaspora—continue that legacy. “Education isn’t just encouraged,” a young Bohra medical student told Jaffna Monitor, “it’s expected. We may be a small community of just a few thousand, but you’ll find our women in almost every field.”

Even within the community’s religious structure, Bohra women take on formal and meaningful responsibilities. “We run community welfare programs, lead literacy drives, and play vital roles in healthcare outreach and disaster relief,” said one community member.

“We even pray in the same mosque as men—during the same congregational prayers,” she explained. In most other Muslim congregations, such a practice remains rare, with women often praying in separate areas—or, in some cases, not attending mosques at all.

Ashara Mubaraka: A Global Gathering with Local Impact

Every year, during the first ten days of the Islamic month of Muharram, the Dawoodi Bohras observe Ashara Mubaraka—a solemn commemoration of the martyrdom of Imam Husayn, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, at the Battle of Karbala. Each year, Syedna selects a host city to deliver the central sermons, drawing tens of thousands of Bohras from around the world for ten days of sermons, prayers, and communal reflection.

Ashara in Colombo: From Resilience to Renewal

Colombo first hosted Ashara Mubaraka in 2008 under the leadership of the late Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin. The event brought together over 15,000 Dawoodi Bohras from abroad and nearly 2,000 local community members, briefly transforming the city into a hive of spiritual energy and cross-cultural exchange.

In 2019, Ashara returned to Colombo—but under profoundly different circumstances. Just months earlier, Sri Lanka had been rocked by the Easter Sunday terror attacks, which killed over 250 people and shattered the nation’s sense of security. With tourism in freefall and global confidence shaken, most international visitors stayed away.

Yet it was during this moment of national crisis that Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin accepted the Sri Lankan government’s invitation to host Ashara in Colombo. The event’s theme that year was “We Believe in Sri Lanka”.

From September 1–10, more than 21,000 Dawoodi Bohras from over 40 countries arrived in Sri Lanka. Hotels from Negombo to Mount Lavinia were fully booked. The community reserved over 3,000 hotel rooms and 200 serviced apartments, generating an estimated economic impact of over USD 31 million (LKR 5.6 billion). Sri Lankan tourism officials later credited the event with helping restore international confidence in the country as a safe destination.

“It was the Bohras who came first,” said Roshan, a hotelier in Negombo, with evident gratitude. “After the Easter attacks, we had zero tourists. But when the Bohras arrived in such numbers, it sent a message: Sri Lanka is safe again. For that, every patriot in this country owes them a debt of gratitude.”

2025: A New Chapter in a Familiar City

In 2025, while the main Ashara Mubaraka gathering took place in Chennai, Colombo once again emerged as a key spiritual and cultural hub. From June 27 to July 5, over 10,000 devotees from Sri Lanka and abroad gathered for one of the largest regional Bohra conventions to date.

Though Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin delivered his sermons from Chennai, Colombo hosted parallel programmes, combining religious observances with community service, cultural reflection, and economic revitalization.

The Return of Jaffna’s Bohras

Arguably the most moving chapter in the Dawoodi Bohras’ Sri Lankan story lies in Jaffna—though few outside the community know it, a local Bohra Muslim told Jaffna Monitor.

“We have our own Husaini Masjid in Jaffna, built in the early 20th century. For decades, this mosque served as the spiritual anchor for a small but active Bohra community in the north.”

That chapter came to a tragic halt in 1990 when the LTTE issued an ultimatum: all Muslims must leave Jaffna within 48 hours. Most fled. But around forty Bohras, determined to protect their beloved masjid, took shelter inside. Surrounded by shellfire and cut off from supplies, they remained there for days.

“When two young boys stepped out in search of food,” he recounted, “they were tragically killed and later buried in the mosque grounds.”

Eventually, under a temporary ceasefire, the group staged a harrowing escape—on foot and by boat—led by Mulla Moosajee Adamjee, carrying a white flag. Their departure marked the end of the Bohra presence in Jaffna for nearly three decades.

In the post-war years, that story has come full circle. Acting on the directive of Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin, the Husaini Masjid was restored. Today, twelve Bohra families live nearby—quietly rebuilding a legacy once nearly lost.

A Model for Our Times

For nearly two centuries, the Dawoodi Bohras have lived through colonial rule, independence, civil war, and economic collapse—yet they have never wavered in their identity. They remained true to their faith, loyal to the land they call home, respectful of others, and remarkably untouched by the waves of extremism that have shaken the region.

The Bohras offer one of Sri Lanka’s most valuable lessons. And perhaps most powerfully, they present a silent, dignified challenge to other communities—especially Sri Lankan Tamils, both at home and in the diaspora.

Be rooted in the soil you live in. Be loyal to the country that shelters you. Be a patriot wherever you make your life. Resist the seductive pull of hatred. Choose dignity over bitterness. Discipline over chaos. Coexistence over conflict. Never allow even a trace of extremism to take root. Build a life that flourishes—and help others flourish alongside you.