Why South Asia Reveres Books-and Fears Their Destruction

Irrespective of religion, across the Indian subcontinent, books have long held an exalted status. In the indigenous spiritual traditions that emerged from this land-Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism-knowledge is not merely valued; it is venerated in the highest order. In homes, temples, and schools across the region, people treat books with profound reverence-never touching them with their feet, and if done accidentally, offering an immediate gesture of apology.

Even the accidental burning of paper is considered blasphemous by many, as it symbolizes disrespect to knowledge itself. This deep cultural sanctity makes the destruction of books in South Asia exceptionally rare," a historian told Jaffna Monitor. "And when it does happen, it is both spiritually and emotionally devastating." He elaborated that such acts are believed to invite long-lasting karmic consequences, reverberating through cycles of collective consciousness. "That’s why," he said, "people are afraid-even those with power hesitate to commit such a sacrilege.

Nalanda to Nazi Germany: Fires That Still Burn in Humanity’s Conscience

Before 1981-before the burning of the Jaffna Public Library the last recorded destruction of a major library in the Indian subcontinent occurred nearly 800 years earlier, in the 12th century, when the Central Asian invader Bakhtiyar Khilji attacked Nalanda University in present-day Bihar.

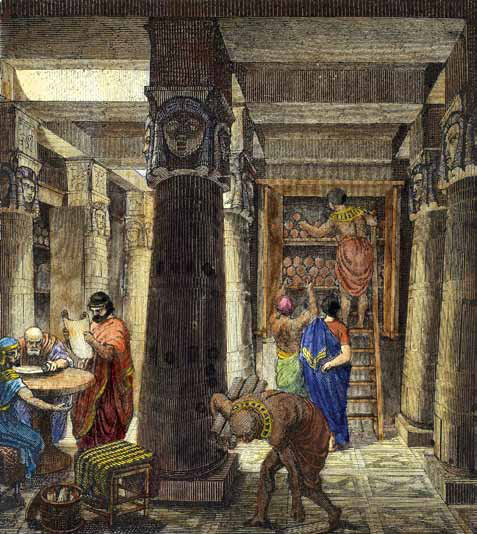

Nalanda, a globally renowned Buddhist center of learning, housed an immense three-block library complex-so vast that one of its towers was said to rise nine stories high.

It contained hundreds of thousands of handwritten manuscripts on science, medicine, logic, philosophy, and more, accumulated over centuries. When Khilji’s army set it ablaze, the fire reportedly burned for days. Even after centuries, the loss of Nalanda is remembered as a civilizational wound-one that the Buddhist world has never truly healed.

In global history, deliberate acts of violence against repositories of knowledge are rare-but when they occur, they carry chilling symbolic weight. The burning of the Great Library of Alexandria whether by Julius Caesar’s forces in 48 BCE or through later destruction attributed to Christian zealots or Muslim conquerors-marked the irreversible loss of a vast trove of ancient wisdom. The destruction of Baghdad’s House of Wisdom by Mongol invaders in 1258, during the sack of the Abbasid Caliphate, was another civilizational catastrophe; legend has it that the Tigris River ran black with the ink of drowned books. Closer to our time, in 1930s Germany, the Nazi regime conducted public book burnings across cities targeting the works of Jewish intellectuals, Marxists, pacifists, and any writer or thinker the regime feared.

Historians have long noted that these attacks on knowledge were condemned even more fiercely than the mass killings that accompanied them. The death of scholars and civilians was tragic, but the annihilation of accumulated learning-meant for generations yet unborn was viewed as a crime against humanity itself.

Where the Dhamma Was First Written-And Then Burned

Buddhism has always revered knowledge. The greatest man ever to walk this earth, Gautama Buddha, preached wisdom, rational thought, and non-violence. “Wisdom dispels the darkness of ignorance,” he said-one of many teachings that place paññā (wisdom) at the very heart of the Dhamma. The Buddha did not demand blind faith; instead, he urged inquiry, introspection, and understanding. “Do not accept anything by mere tradition… but after observation and analysis, when you find that it agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and benefit of one and all, then accept it and live up to it,” he told the Kalamas (Kalama Sutta).

For centuries, Buddhist monks were the guardians of knowledge. Monasteries across South and Southeast Asia functioned not just as spiritual retreats, but also as de facto universities and libraries. Monks served as scribes, translators, preservers, and teachers of texts-from palm leaf manuscripts to meticulously copied parchments.

Unlike many other religious traditions, Buddhism was not spread by conquest, but through teaching-rooted in logic, compassion, silence, discipline, and devotion. It was the quiet endurance of the written word-books and texts-and the spoken truth that carried the Dhamma across oceans and centuries.

In fact, it was here in Sri Lanka, at Aluvihara in Matale during the 1st century BCE, that the oral teachings of the Buddha were committed to writing for the first time. This act-carried out by monks fearing the loss of the Tripiṭaka due to famine and war-resulted in the Pāli Canon: the world’s first complete written Buddhist scripture. It remains one of the greatest contributions Sri Lanka has made to global civilization.

In Buddhist tradition, the act of burning a book transcends the mere destruction of parchment or palm leaf. It signifies the extinguishing of truth, insight, and the very path toward liberation. Such an act stands in direct opposition to everything the Buddha and his Dhamma represent. The Buddha himself profoundly warned against ignorance as humanity's greatest enemy, stating: "There is no fire like passion, no shark like hatred, no snare like folly, no torrent like craving" (Dhammapada). In this context, the destruction of a library is not simply a worldly crime; it is a karmic betrayal of everything the Dhamma holds sacred.

It's a searing paradox in Sri Lanka's history: an ideology claiming to embody Sinhala Buddhism-a tradition supposedly grounded in compassion, wisdom, and enlightenment, and one whose collective memory still mourns the devastating loss of Nalanda University to a foreign invader-was twisted to commit, justify, or silently condone an act of unparalleled barbarism against knowledge on the island.

Eight centuries after Nalanda burned, in 1981, it was Sinhala-Buddhist mobs, backed by state power and emboldened by two bloodstained UNP Cabinet Ministers present in Jaffna, who, with the silent inaction or tacit approval of the Army Commander and Police Chief also in Jaffna that night, torched the city's most cherished symbol of learning: the Jaffna Public Library. Over 97,000 books, including irreplaceable ancient ola-leaf manuscripts, Tamil literary classics, and historical records, were reduced to ash. In that single night of unspeakable vandalism, they did more than burn books - they spat on the very soul of what the Buddha and his Dhamma stood for.

A State-Sanctioned Crime

Sinhala nationalist forces and the Sri Lankan state often find themselves at a loss when it comes to the 1981 burning of the Jaffna Public Library-because, unlike many other atrocities, they can’t pin this heinous act on the LTTE, nor can they claim that the LTTE provoked it. At the time, there was no declared war, and the LTTE was merely an emerging group-a handful of young men scattered across a few hideouts, far from the formidable force it would later become.

“One observer told Jaffna Monitor that the presence of two Cabinet Ministers, along with the Army Commander and the Police Chief-all in Jaffna on the very night the library was set ablaze-was no coincidence, but a calculated show of state power.

By orchestrating the destruction of one of Asia’s finest libraries, the then UNP-led government sent a chilling message to the Tamil people: ‘If you dare to raise your voice-if you demand dignity, rights, or recognition-we will silence you. We will go to any extent to erase your culture, your memory, your very identity.’” He further noted, “It was a calculated act of terror designed to intimidate an entire community into submission''

More Than a Library: Jaffna’s Temple of Knowledge

The burned Jaffna Public Library had housed over 97,000 books and irreplaceable manuscripts-including the only known original copy of the Yalpana Vaipavamalai (The History of the Kingdom of Jaffna), miniature editions of the Ramayana, accounts by early explorers in Ceylon, and a trove of ancient palm-leaf manuscripts vital to Sri Lanka’s Tamil-speaking communities.

A Sinhala observer once wrote, after visiting Jaffna, that the Jaffna Public Library stood apart from every other library in the country: “It’s not just considered a library. It is treated like a temple of knowledge. I have visited many libraries across Sri Lanka and the world, but this is the only one where you are expected to remove your shoes or slippers before entering. You enter this library the same way you would enter a Buddhist vihāra or temple - with reverence.

” My father once told me, “For me, and for many young people of my generation, the most revered place in Jaffna wasn’t a temple - it was the Jaffna Public Library.” To him, it was a sanctuary, a sacred space where dreams were born and minds were shaped. He would often share stories of his youth - how, as a teenager, he cycled for miles from a remote village, braving sun and rain, just to spend precious hours inside that hallowed hall of knowledge. He spoke of the silence, the scent of old pages, and the feeling of stepping into a world far beyond the confines of oneself. He would sit there for hours, lost in books - until, like clockwork, the kindly librarian would walk up with a gentle smile and say, “Thambi, we’re closing now.” For him, those hours were not just about reading; they were about being part of something far greater than oneself.

The Origins of the Jaffna Public Library

The story of the Jaffna Public Library began in 1933, when scholar and philanthropist K. M. Chellappah launched a modest initiative lending books from his home in Puttur. Joined by a group of like-minded community members, he formed a local committee and served as its secretary. What started as a single-room collection of roughly 1,000 books soon sparked a far more ambitious vision.

The dream of a permanent, purpose-built library quickly gathered momentum. Community leaders mobilized support, securing donations from local well-wishers and from the Tamil diaspora in Malaysia and Singapore. Their collective determination laid the foundation for what would soon become one of Jaffna’s most iconic landmarks.

Among the early champions was Dr. Isaac Thambiah, a lawyer and intellectual, who served as vice-chairman of the committee established in 1934 to formally found the Jaffna Public Library. His personal collection of books significantly enriched the growing repository.

Renowned Indian architect V. M. Narasimhan was commissioned to design the library in the graceful Indo-Saracenic style-a sophisticated fusion of Mughal, Hindu, and colonial architectural influences. Its soaring domes, sweeping colonnades, and pristine white façade bestowed a sense of timeless elegance upon the city. To ensure the library adhered to international standards, the eminent Indian librarian S. R. Ranganathan-widely regarded as the father of library science in India offered expert guidance on cataloguing and organizational systems.

But the effort was not limited to India and Ceylon alone. Fr. Timothy Long, an Irish priest and rector of St. Patrick’s College from 1936 to 1954, played a critical role in bringing the library to fruition. He traveled extensively, including to the United States, to raise much needed funds for the project.

Jaffna’s first mayor, Sam A. Sabapathy, was instrumental in translating vision into reality. He laid the foundation stone for the new library on March 29, 1954. Five years later, in 1959, the first major wing of the Jaffna Public Library was officially inaugurated by then Mayor Alfred Duraiappah-marking the birth of what would grow into one of South Asia’s most revered centers of learning.

By the 1970s, it had grown into one of South Asia’s largest and best-equipped libraries. Its influence reached far beyond the Jaffna peninsula-Sinhala students, Indian scholars, and international academics all came to access its unmatched resources and pursue serious intellectual work.

Never Exclusive to Tamil Culture

Though it stood in the heart of a Tamil city and was deeply cherished by the Tamil people, the Jaffna Public Library was never exclusive to Tamil culture. Its vast collection reflected a spirit of intellectual openness housing not only Tamil literary treasures but also Sinhala texts, Buddhist scriptures, and works in English and other languages. It was, at its core, a monument to pluralism.

Elders who frequented the library told Jaffna Monitor that researchers from India and beyond would travel to Jaffna specifically to access its archives, often marvelling at the depth, rarity, and diversity of the materials it held. “This library was a cultural shrine,” one elderly man recalled. “It embodied the pride and dignity of the Tamil people, yes-but it also welcomed Sinhala texts and rare Buddhist manuscripts.”

He went on to explain that, just as Nalanda University had once been the epicentre of Buddhist learning in ancient India-drawing seekers from across Asia-the Jaffna Public Library had become a beacon for Tamil scholarship in modern Sri Lanka. Its very presence, he said, was an act of cultural self respect in a nation increasingly dominated by Sinhala majoritarianism. And perhaps that, more than anything else, is why it was burned-to erase a living symbol of Tamil knowledge, heritage, and intellectual power.

The Anatomy of a Cultural Crime

On the evening of May 31, 1981, tension hung heavy over Jaffna. “The town was already on edge,” recalled an elderly witness who spoke to Jaffna Monitor. That day, the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF)-then the leading Tamil political party advocating for autonomy-was holding a major election rally in the heart of the town. In what many believed to be a deliberate provocation, the ruling United National Party (UNP) sent two senior Sinhalese cabinet ministers Cyril Mathew, a known Sinhala Buddhist hardliner, and Gamini Dissanayake, a powerful figure

within the government-to “observe” the event. Their real motive, many felt, was to provoke and disrupt. They arrived in Jaffna accompanied by hundreds of heavily armed Sinhalese police officers and paramilitary personnel. The atmosphere quickly turned volatile. Eyewitnesses reported confrontations between Tamil civilians and security forces-some of whom were intoxicated, hurling anti-Tamil slurs, and behaving aggressively.

Amidst the rising tension, gunmen believed to be from the Tamil militant group PLOTE (People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam) opened fire, killing two policemen. While the details of the shooting remain unclear, it became the spark-or rather, the pretext-for what appeared to be a pre-planned campaign of violence. The security forces and paramilitaries, already on standby, seized the moment as a green light to unleash chaos.

For the next 72 hours, Jaffna plunged into anarchy, witnessing a chilling display of systematic, state-sponsored destruction. Police and organized mobs, acting under the direction of political actors, unleashed coordinated attacks across the town. Dozens of Tamil-owned businesses, homes, political offices, and newspaper presses were either burned, looted, or both.

That night, scores of Sri Lankan police and government-sponsored paramilitaries fanned out across the city on a rampage It began with targeted reprisals: the downtown office of the TULF was stormed and set ablaze, as was the home of the local TULF Member of The outside view of the burned Jaffna Library before its renovation Parliament, V. Yogeswaranen. The attackers did not stop there.

The Cultural Genocide

On the second night of the pogrom-June 1, 1981-Jaffna had already been scarred. Its homes smouldered, its streets were littered with the ashes of Tamil businesses and newspapers, and its people trembled in disbelief. But the arsonists, backed by political power, were not finished yet. There was one final target, one ultimate symbol left to destroy. Whether they had initially overlooked it, or whether a call from Colombo gave the final instruction, they turned toward the beating heart of Tamil intellectual and cultural pride-the Jaffna Public Library.

According to numerous eyewitnesses many of whom are still alive and spoke to Jaffna Monitor-the scene that unfolded was terrifying in its precision. After dusk, uniformed policemen and plainclothes men, carrying kerosene cans and sacks, began to gather around the library. Just past 10:30 p.m., flames began to rise. Jaffna’s fortress of knowledge, its temple of learning, was deliberately set ablaze.

Attempts by then-Jaffna Municipal Commissioner C.V.K. Sivagnanam to dispatch fire trucks were thwarted, as armed forces encircling the Jaffna Public Library turned them away. By morning, all that remained of the iconic institution were scorched walls and the haunting scent of charred paper.

To ensure the building was completely destroyed, metal torches were used-alongside kerosene and, according to some accounts, chemical accelerants. The inferno raged unchecked throughout the night, with plumes of thick black smoke curling into the sky, visible for miles beyond Jaffna town.

Residents stood helplessly on rooftops, balconies, and in gardens - eyes brimming with tears and anger - as they watched their cultural pride and intellectual soul reduced to ash. Among them was Rev. Fr. (Dr.) Hyacinth Singarayar David, who witnessed the blaze from his school balcony. Stricken by shock and grief, he went to bed that night and passed away in his sleep due to a massive heart attack.

Multiple eyewitnesses even recall seeing the ministers standing calmly on the veranda of the Jaffna Rest House, a government guesthouse just across the street, silently observing the inferno as it consumed the library.

An independent fact-finding mission from the Movement for Inter-Racial Justice and Equality (MIRJE) visited Jaffna shortly after the atrocity and issued a clear, unambiguous conclusion: “There is no doubt that the attacks and the arson were the work of some 100–175 police personnel.” The perpetrators were not an uncontrollable mob-they were agents of the state.

Silence, Denial, and Mockery: The Aftermath of Jaffna’s Inferno

The next day, government ministers downplayed the attack, suggesting that a few policemen had acted irresponsibly and that the violence had escalated beyond their control. The narrative that the destruction was the unintended consequence of spontaneous disorder was repeatedly promoted by state media and echoed by government officials for years.

Most damning of all was the silence of President J. R. Jayewardene. He neither condemned the atrocity nor ordered any serious investigation. National newspapers gave the incident only minimal attention, treating the burning of one of South Asia’s greatest libraries as a minor news item.

In Parliament, when Tamil Members of Parliament raised anguished questions about the incident, they were mocked and heckled by government benches. Several Sinhalese hardliners openly suggested that if Tamils felt aggrieved or discriminated against, they should leave Sri Lanka and go to India - a refrain that had become a frequent insult hurled at Tamils throughout the 1970s and early 1980s.

The burning of the Jaffna Public Library concluded with denial and impunity; no one was held accountable. This lack of justice, combined with the heinous crime of destroying a library, effectively terrorized an entire generation of Tamil youth.

The Day They Burned the Buddha

The heinous act of burning the Jaffna Public Library transcended the mere destruction of books; it shattered the very soul of a civilization. In that inferno, memory was extinguished, wisdom suffocated, and truth brutally murdered. For countless horrified witnesses, it was tantamount to burning the Buddha himself.

In one of the most haunting literary responses to this cultural crime, renowned Tamil poet and scholar Prof. M. A. Nuhman captured the raw, unyielding agony and gravity of the act in his searing poem, Murder of Buddha, poignantly translated into English by S. Pathmanathan. This is no mere lament for a lost building; it is a blistering, unforgiving indictment of a nation's conscience. It lays bare the profound betrayal of Buddhist values by the very hands that claimed to defend them, exposing the grotesque, soul-crushing irony of setting fire to sacred knowledge in the ruthless, consuming blaze of power.

We end with this poem - not merely as literature, but as testimony. It speaks with a moral clarity that no article can fully match.

Murder of Buddha

by Prof. M. A. Nuhman

(Translated by S. Pathmanathan)

Last night I dreamt

Buddha was shot dead by the Police —

guardians of the law.

His body, drenched in blood, lay upon

the steps of the Jaffna Library.

Under cover of darkness, the ministers arrived:

“His name is not on our list.

Why did you kill him?”

they asked, anger rising.

“No, sir. There was no mistake.

Without killing him, it was impossible

to harm a fly — therefore…”

they stammered.

“Alright then. Hide the corpse,”

the ministers ordered and departed.

The men in civvies dragged the body into the Library.

They heaped the books — ninety thousand in all —

and lit the pyre with the Sigalovada Sutta.

Thus the remains of the Compassionate One

were burned to ashes, along with the Dhammapada