By air, by sea, and now—after almost two decades—by land. My journeys to Jaffna had always been shaped by the shifting tides of Sri Lanka’s civil war. I had flown many times into the heavily fortified Palaly Base Hospital to treat injured soldiers. I had sailed across the uncertain seas in 1994 with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to assist the medical students of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna, in completing the final examination for the medical degree (MBBS- Jaffna). Yet, despite all those years of travelling to the peninsula, there was one route I had never taken: the A9 highway, the historic land link between the North and the rest of the country.

Even before the war, circumstances had never taken me down that road. After 1983, the chance vanished entirely. The A9 was cut off, barricaded, mined, and fought over. It became a mythical artery—spoken of constantly, but inaccessible to millions. The people of Jaffna found themselves relying on precarious alternatives, such as the notorious Kilali route, a narrow escape route where danger lurked in every direction. I would never have attempted it; too many had paid a heavy price.

In February 2002, however, the Norwegian-brokered Ceasefire Agreement changed everything. For the first time in almost twenty years, the A9 was open beyond Vavuniya. Checkpoints, armed guards and border controls remained, but the journey was possible. Safe enough, we were told, for civilians. Safe enough to witness with my own eyes the land that for years had been known simply as “Wanni”—a place abstracted in media reports and whispered accounts, yet unseen by most people in the South.

When an invitation arrived at that moment, I felt as though history itself had called.

It came from a man I deeply respected: the late Rev. Fr. Gilbert Perera OMI, who was the parish priest of Polonnaruwa during my tenure there. He was now the Diocesan Director of Caritas in Anuradhapura, leading social work across the region. Our friendship, built long ago on a foundation of mutual trust, remained as firm as ever. When he told me he needed my presence on a special journey to Jaffna, I sensed it was more than an ordinary visit.

Caritas, founded in Germany in 1897, grew out of a simple but powerful idea: love expressed through service. It sought to strengthen families, uplift the poor, promote justice and restore dignity to lives disrupted by conflict and deprivation. In Sri Lanka’s long war, Caritas played a quiet but vital role, moving at the grassroots level where suffering was most acute.

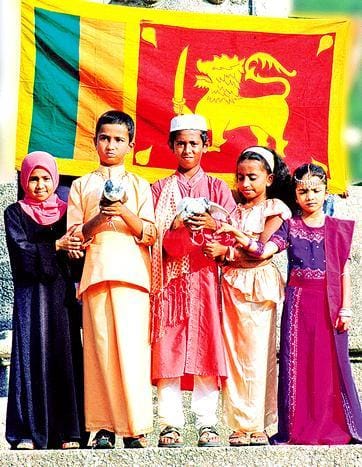

Now, inspired by the ceasefire and hoping to seize this fragile moment of peace, Caritas in Anuradhapura and Jaffna had designed a “live-in family exchange”—a program where families from the South would stay with families in the North. In a country wounded by two decades of mistrust, fear, displacement, and propaganda, the concept was bold: real human connection to counter imagined fears, shared meals to replace suspicion, and personal encounters to rebuild bridges between Tamil and Sinhala communities.

Fr. Gilbert asked me to join sixty parishioners on this mission of goodwill. His joy when I accepted spoke volumes. Perhaps my presence gave him a sense of reassurance; perhaps it was simply the warmth of old friendship. For my part, I felt honoured. I wanted to witness this rare opening in the walls that had divided our country for so long.

The Army was informed of our journey. They advised us to carry identity cards, photocopies, vehicle documents and other essentials. The officers assured us of their support and arranged breakfast for the entire group. From the LTTE side, of course, no promises were possible. Yet travelling with respected clergy, and armed with nothing but the desire for peace, we hoped for courtesy rather than confrontation.

At 5 a.m. on the 5th of July 2002, our group set out from Anuradhapura in a jeep and a bus for the 198-kilometre journey. The early morning light, filtering through thin mist and sleepy villages, carried an air of expectancy. Up to Vavuniya, the road was predictable—military checkpoints, familiar landscapes. But we all knew the true journey began at Omanthai.

Our first major stop was at Iratperiyakulam Army camp, where a friendly officer—someone I had known for years—had arranged a generous Northern breakfast of thosai, vadai and sambar. It was a thoughtful gesture, and the group enjoyed the unexpected hospitality with gratitude. Perhaps it was a sign of the goodwill the ceasefire had kindled.

At Omanthai, the southernmost border of Tiger-controlled territory, the Army handled formalities efficiently. Identity cards were inspected, vehicle details recorded, and we were sent onward into the eerie stillness of No Man’s Land—a stretch of land that neither side fully occupied, a scar cut across the map. Six hundred metres later, we approached the LTTE checkpoint at Puliyankulam.

There was an unmistakable tension. How would the Tigers react to a large group of Sinhala civilians? Would they delay us—or worse, turn us back?

To our relief, the process was unexpectedly smooth. LTTE officers collected photocopies of identity cards, revenue licences and insurance certificates. A handwritten permit in Tamil with the rubber stamp of the Tigers was issued, allowing us to travel northward. It became clear that Rev. Fr. Gilbert’s presence was a powerful bridge. The officers were courteous, and within minutes, we were back on the A9—now inside territory that had been cut off from the rest of the island for decades.

The transformation of the landscape was immediate. The smooth highway turned into a patchwork of broken tarmac and gravel. Landmine craters dotted the roadside. Bridges had been reduced to skeletons of concrete and twisted steel. Roofless houses, shattered churches, kovils, bullet-riddled statues and abandoned shops stood like ghosts of another era. Villages that once bustled with life now seemed suspended in time—empty, silent, waiting.

Kilinochchi soon came into view, unmistakably the administrative heart of the LTTE. Their political office, the residence of the head of their political wing, and the hall where foreign delegations had once met LTTE representatives were all located on a byroad just a few metres from the main road, and we decided to pay a visit. To my surprise, with the permission of their guards, we were allowed to observe these structures at close quarters. A year earlier, such an act would have been unthinkable.

What we did not realise until then was that our journey coincided with a major LTTE commemoration. The 5th of July was Black Tiger Day, marking the death of their first suicide bomber, Vallipuram Vasanthan, better known as Captain Miller, whose attack at Nelliady during the 1987 Vadamarachchi Operation had become a symbol of sacrifice within their ranks. The streets that day were lined with flags and photographs. Security was tight, but subdued. Armed cadres, unarmed female cadres on bicycles, and LTTE policemen on new motorcycles patrolled the area. We stopped to take photographs, and to our surprise, they posed willingly. It was surreal—a moment suspended between war and peace, hostility and hospitality.

As we continued north, the ruins of Elephant Pass came into view. The land was barren, almost lunar in appearance. The site of some of the most intense battles of the war lay in silence, marked only by the rusting remains of armoured vehicles from both sides. One object stood out starkly: the iron-clad bulldozer used by the LTTE during the 1991 assault to break through the forward defence lines of the Elephant Pass Army camp. It lay abandoned by the roadside, a reminder of the ferocity that once engulfed this narrow strip of land. No doubt it was a great opportunity for a photo shoot, and I did not miss that.

North of Elephant Pass lay Pallai—a town reduced to emptiness. Then came the LTTE checkpoint at Muhamalai, where our earlier permit was verified. Beyond it stretched another No Man’s Land, and finally the government-controlled entry point where armed personnel stood behind high mounds of sandbags. After another round of checks, we crossed into territory once again under state control.

Between Muhamalai and Chavakachcheri, the scars of war were unmistakable. Heavy fighting had devastated the region. Coconut and palmyrah trees stood burnt and blackened by artillery fire. Houses were pulverised. The land was dotted with landmine warning signs, urging travellers to keep strictly to the road. Demining teams, taking advantage of the ceasefire, worked under the punishing sun to make the land safe again.

As we reached Chavakachcheri, signs of civilian life gradually reappeared, though the destruction remained overwhelming. Another ten kilometres brought us to Jaffna—a city I had known in different eras, but never in such a state. It had taken nearly twelve hours from Anuradhapura, yet the journey felt far longer. War had etched itself into every kilometre we passed.

At the Caritas Jaffna headquarters, families from the North awaited us—smiling, hopeful, curious. Their welcome was warm and sincere, radiating a sense of unity that transcended the divisions of the past twenty years. Some of us stayed at the Caritas centre; others were hosted by Tamil families, who opened their homes and hearts despite their own hardships.

Over the next two days, meetings, discussions, meals and shared experiences filled our time. Sessions were conducted in Sinhala and Tamil, with translation ensuring that no voice was left unheard. Experts facilitated conversations on peacebuilding, reconciliation and the challenges of rebuilding shattered communities. We visited iconic locations in Jaffna—the historic Fort, the Jaffna lagoon, the Public Library resurrected after its tragic burning, the Duraiappa Stadium and the war-scarred streets. For many in our group, these were revelations: Jaffna was not the distant, threatening “other” they had been taught to fear, but a community of people remarkably like themselves—resilient, warm and yearning for peace.

Communication was sometimes difficult; accents differed, idioms varied, and decades of separation had created unfamiliarity. Yet the human connection grew stronger. Children played together without hesitation. Mothers exchanged recipes and stories. Elderly participants shared memories of a time before the war, when travelling between Jaffna and the South was unremarkable. It was perhaps the first initiative of its kind—an effort rooted not in politics but in human fellowship.

When the time came to leave, emotions ran high. Tears flowed openly—from both Tamil and Sinhala participants. In just two days, bonds had formed that felt deeper than mere friendship. Promises were made to continue the exchange, to invite families from Jaffna to Anuradhapura, to nurture the fragile sprout of peace that had taken root.

That morning, as our bus prepared to depart, a quiet sadness settled over us. Yet beneath it lay hope—the belief that the long years of conflict were finally giving way to reconciliation. Participants on both sides spoke of a future in which people could travel freely, live without fear, and once again think of themselves as citizens of one nation.

But history had other plans.

What unfolded in the years after our journey proved devastating. The peace that seemed within reach slowly eroded. Mistrust resurfaced. Negotiations faltered. Isolated incidents escalated into major confrontations. Despite the best efforts of civilians, clergy, activists and countless ordinary people, the ceasefire crumbled. The A9, which had briefly symbolised unity and possibility, once again became a battleground. The hopes nurtured during that visit—the friendships, the shared meals, the dreams of a harmonious future—were swept away by the return of war.

Seven long years would pass before I saw Jaffna again—only after the conflict ended in May 2009. When I finally returned, I saw the immense toll the war had taken. Entire villages had disappeared. Farmlands lay idle. Homes, wells, schools and churches were scarred or destroyed. The human cost was immeasurable. And yet, even amidst the ruins, echoes of that 2002 journey remained—a reminder of what peace could have achieved, had it been allowed to survive.

Our journey in 2002 was more than a road trip. It was a glimpse of an alternate future—a future where communities divided by history and politics might have found their way back to each other. The peace mission carried a profound message: that reconciliation is built not only through treaties or official dialogues, but through human bonds formed in trust and compassion. That trip taught me that peace is fragile, precious, and must be protected at all costs.

Yet, as the war resumed, that opportunity slipped away. The promise of 2002 stands today as both an inspiration and a reminder: peace can be made real when people have the courage to reach out to one another—but it can also vanish when goodwill is overwhelmed by conflict.

The A9 we travelled that day was more than a road. It was a symbol of hope. And though the hope of that time was shattered, the memory of what was possible remains an enduring reminder of the road Sri Lanka must continue to strive toward—one of unity, understanding and lasting peace