The temporal evolution of Hindu iconography was the result of changes in the philosophical understanding on the nature of existence and the ability to express these insights through suitable artistic media. In addition to being a source of artistic inspiration these changes also trigger reflection and introspection amongst religious seekers. The journey from the abstract and amorphic Shivalinga through the early anthropomorphic ‘Pasupathi’ of the Indus Valley civilisation and the further exuberant refinements culminating in the ‘Ananda Thandava’ (or the dance of bliss) of Natarajah - the Lord of Dance, illustrates this transition perfectly. In understanding these imageries ‘what they represent’ is more important than what they ‘seem to look like’ to a casual observer with a fleeting interest in Hindu iconography. The evolution of Hindu iconography is deeply intertwined with the recognition that divinity may be conceptualised through aniconic (devoid of form), non-anthropomorphic (non-human) or anthropomorphic (human-like) imagery depending on the seeker’s (or devotee’s) own abilities, imagination and intellectual development. This principle is central to the development of Shiva iconography across the ages.

The Dual Nature of the Divine in Hinduism

Non-Anthropomorphic iconography: Hindu philosophy presents the view that the ultimate reality is boundless and devoid of form, attributes, or character (Nirguna). This characterization is not dissimilar to how modern theoretical physicists would view the universe. This realisation led to the representation of divinity as an amorphous column – the Shivalinga. The puranas illustrated this concept allegorically as a column of fire – with neither beginning nor end which tamed the human ego. The ‘Shivalinga’ form encapsulates this concept and Linga worship can be traced to antiquity. Even though artefacts of Shivalinga excavated from the cities that were part of the Indus valley civilisation (3300 -1300 BC) predate the Vedic period (1500-500 BC), it was during the post-Vedic periods that the Shivalinga solidified as the primary non-anthropomorphic mode of worship.

Simplifying the iconography of ‘Shivalinga’ to a simple Phallic worship by ‘scholars’ from the colonial period and commentators of the post-colonial period demonstrates the limitations of simple pattern recognition in archaeological explorations. Whilst such distortions may not be deliberate, they failed to appreciate the profound ideas such as the ‘Nirguna Brahman’ – the formless, characterless and limitless reality, that continues to fascinate physicists and philosophers alike to the present day.

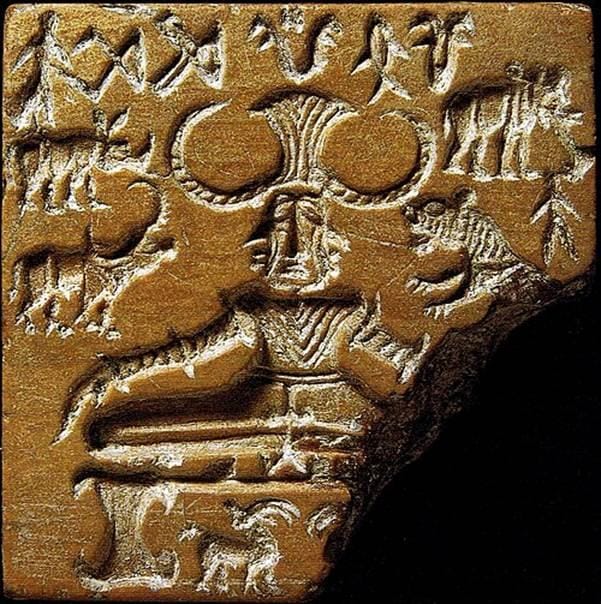

Anthropomorphic iconography: The earliest roots of worship to anthropomorphic imagery can also be traced to the Indus Valley civilisation. Human beings are bound by forms that are familiar to them in all aspects of life including the spiritual domain. It was therefore in keeping with human nature that this formless reality was conceptualised as ‘saguna’ – as a personal deity across many civilisations. The ‘Pasupati seal’ excavated from Mohenjo-daro (>2200 BC) depicting a supernatural humanoid figure with three faces, deeply in meditation in the wild, surrounded by wild animals may be an example of early man’s attempts to see divinity through humanoid forms that better resonated with their lived experiences.

The Vedic Period (1500-500 BC): Reference to potentially anthropomorphic imagery can also be found in the Vedic texts. The earlier parts of the Vedas such as Rigveda contain many hymns praising several deities such as Indra, Agni, Varuna and Mitra. These were however often associated with natural cosmic forces and any association between these deities and human(oid) imagery is speculative. The Vedas do not explicitly depict any of these deities anthropomorphically, though the reference to “Thriyambakam” (or the Three-eyed one) in Rig Veda does suggest a human form being alluded to – albeit indirectly. In this context the failure to find any religious imagery in the other excavation sites in South India (600 BC) – Keeladi, Adichanallur and Arikamedu etc. presents interesting possibilities/hypotheses of how these early Vedic and post Vedic communities may have conceptualised divinity.

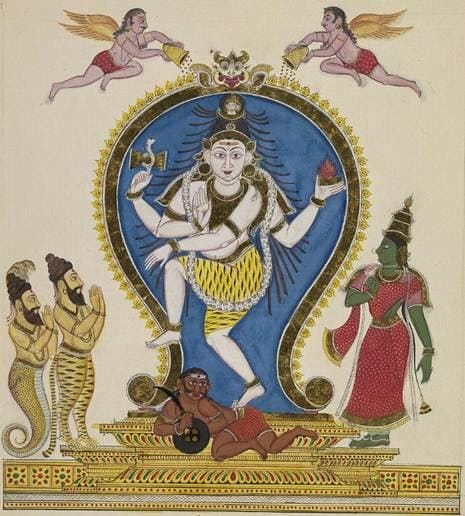

The Shiva Thandava (The Dance of Shiva): The form of ‘Dancing Shiva’ in the post-Vedic period carries the anthropomorphic iconography to new heights and the evolution of this form is of considerable philosophical and artistic interest.

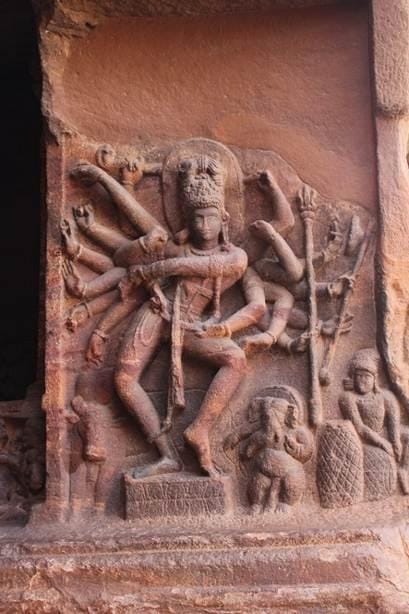

The Gupta Era (3rd-6th century AD): The Gupta period is often hailed as the golden age of Indian art, witnessing significant flourishing of anthropomorphic depictions of Shiva. These included images of Shiva as a celestial dancer. These artefacts perhaps represent the earliest attempts to allow the laity to visualize Shiva performing his cosmic dance in an active and dynamic format. They display divine grace and protection as underlying themes with a balance between serenity and subtle power. The ability to express these opposing attributes concurrently provides testimony to the unique skills of the Gupta sculptors. The importance of this iconography was that it enabled the laity to develop adoration and surrender to a personal god - the hallmarks of Bakthi yoga. The profound impact of these attributes expressed through familiar human forms, no doubt contributed to the resurgence of Hinduism in the Indian subcontinent - somewhat blunted during the pre-Gupta period due to the growing influence of Buddhism and Jainism. These artefacts however lacked the finer and more subtle attributes – aesthetic as well as philosophic, that were to follow in the subsequent iterations.

As the Gupta empire declined, regional styles flourished in the Deccan and South India, further evolving the representation of Shiva as a dancer. These depictions were crucial iconographic stepping stones toward the eventual Nataraja form.

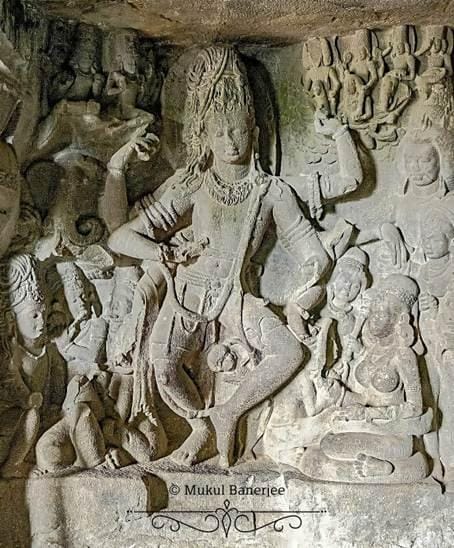

Chalukya Period: The Chalukya empire was a powerful force in the Deccans during the 6th-12th centuries AD. The Chalukya kings such as Pulikeshin II were great patrons of art supporting Buddhist and Hindu sculpture and paintings. The rock carvings of the early Chalukyas, seen at Badami – formally known as Vatapi the capitol city of the early Chalukyas, Ellora caves and several other sites in the Deccans form an important intermediate phase in the evolution of the dancing Shiva iconography. In these carvings, Shiva is depicted performing his dance (the ‘Thandava’), often with multiple arms, capturing intense energy, power and dramatic movement.

The Pallava period (3rd – 9th century AD): The Pallava kings based in Kanchipuram– who were contemporaries of the early Chalukyas were also great patrons of art. The rivalry that existed between the Pallava and the Chalukya kings – political and artistic, is well captured in Kalki’s historic fiction novel ‘Sivakamiyin Sabatham’ (சிவகாமியின் சபதம் or Sivakami’s Vow). Stone carvings in the Pallava temples can be seen as the next phase in the development of the dancing shiva iconography. The sculptures of Kanchipuram created images that were elegant and slender, emphasizing divine grace. The ‘Ananda Thandava’ (the dance of bliss) forms with one leg raised away from the ground first begins to emerge during the Pallava period. King Mahendravarma Pallava (590-630AD) was a great patron of all forms of art and was very well versed in the theory of dance (Narthana shastra) and the images created during his reign bring out these graceful poses - characteristic of south Indian Baratha Natyam, into the Dancing Shiva rock carvings created during his reign.

The Iconographic Transformation: The Ananda Thandavam (or the dance of bliss): A significant iconographic shift occurred between these early Pallava/Chalukya periods and the later Chola era: the transition from depictions of Shiva with both feet firmly anchored to the ground to the iconic Nataraja pose with one leg gracefully raised. The crucial element facilitating this physical and iconographic shift was the advent of advanced metallurgy, specifically the widespread use of bronze and brass casting during the Chola period. Stone carving, the dominant medium for earlier large-scale temple art, posed inherent limitations regarding tensile strength. Sculptors were constrained by the risk of breakage, making gravity-defying, extended limbs and isolated body parts structurally challenging, if not impossible.

The mastery of using copper alloy provided a medium with far superior tensile strength and malleability. This allowed Chola artisans to create structurally stable images with dramatically flared limbs, wildly flowing hair locks, and the complex, dynamic, off-balance pose of the raised leg. The Chola period therefore marks the pinnacle of South Indian bronze casting and the definitive standardization of the Nataraja iconography, utilizing this newly evolved raised-leg pose. This era synthesized the dual visualization approaches by offering a fully anthropomorphic image that simultaneously served as a highly abstract, philosophical diagram of the cosmos.

The Chola Nataraja is a masterpiece of art and philosophy. Philosophically the Chola Natarajah encapsulates the five divine acts of divinity - creation (the drum), sustenance (the abhaya mudra of the raised second right arm), dissolution (the flame on the left arm), dispelling of illusion or ignorance (the demon Apasmara under the feet), and salvation (the raised left foot). The physical possibility offered by the metal medium allowed the theological concept of moksha (liberation) to be perfectly symbolized by the raised foot and an arm pointing the devotee towards that raised leg. The image allows the devotee to see Shiva in an accessible, dynamic human form, while simultaneously forcing contemplation of abstract, cosmic principles. This iconography became the standard not only in South Indian temples like Chitambaram but also spread to Sri Lanka, where Chola influence is evident in the bronze finds at Polonnaruwa.

Modern Times: Continuity and Interpretation

In modern times, both the Shivalinga and the Nataraja form remain central to Hindu worship, serving the devotional needs of the laity who visualize the divine in different ways. The linga continues to be the primary focus in the garbhagriha (the main sanctum) of Shiva temples, such as the famous Muneswaram (Chilaw, Sri Lanka), Thiruketheeswaram (Mannar, Sri Lanka), Thirukoneswaram (Trincomalee, Sri Lanka) and Naguleswaram (Keerimalai, Sri Lanka). Archaeological findings in Sri Lanka provide tangible evidence of the ancient and continuous nature of Shiva worship as an integral component of the Sri Lankan culture. At the ruins of the ancient Tenavaram temple (Thondeswaram) in Matara, a large Shivalingam was unearthed in 1998, along with a Nandi statue dated to the Pallava era. The size of this lingam suggests that it was most likely the principal idol in the temple highlighting the importance of Linga worship in ancient Sri Lanka beyond the Northern province. The Tenavaram temple is believed to be one of the five ancient Ishwarams (Shiva abodes) constructed along the four coasts by Prince Vijaya to protect the island.

The Nataraja has transcended religious boundaries, becoming a global symbol of Indian culture, art, and philosophy. The famous installation at CERN in Geneva, Switzerland—home of the particle physics research organization—symbolizes the modern scientific understanding of cosmic dance and the cycle of matter and energy, bridging ancient spiritual symbolism with contemporary physics.

Conclusion: The evolution from the Shivalinga to the Nataraja is a journey from the abstract cosmic pillar to the dynamic anthropomorphic expression of reality and the nature of existence. This history demonstrates the flexibility within Hindu iconography to accommodate the needs of all devotees—offering both non-anthropomorphic forms for abstract meditation and fully anthropomorphic forms for personal devotion. The transformation across millennia, driven by evolving theology, regional artistic expressions and the advent of superior materials like metal for sculpture culminated in the canonical Nataraja, an image that perfectly captures the entire cosmic cycle in a single, powerful, dualistic form.

The ideas expressed in this article are that of the author and do not reflect the views of the University of Manchester in these issues.