Editor’s Note

The Battle of Elephant Pass has long been remembered through differing — and often opposing — narratives. Many Tamils are familiar with the version told from the LTTE’s perspective. The account that follows offers another vantage point: that of a surgeon who was on duty at Palaly during the siege and witnessed its human cost firsthand. It is presented as a personal historical recollection.

Documenting multiple perspectives is essential to understanding the full complexity of Sri Lanka’s past. This article is published in that spirit.

A Defining Moment in Sri Lanka’s Modern Military History

Elephant Pass—known locally as Alimankada—occupies one of the most strategically decisive locations in Sri Lanka’s geography and history. It is a narrow land corridor, barely a few kilometres wide at its most constricted point, yet it serves as the sole terrestrial gateway linking the Jaffna Peninsula to the Northern mainland. Whoever controls Elephant Pass controls access to Jaffna, its people, its economy, and its military lifelines. For centuries, invading armies, colonial powers, and modern militaries alike understood its value. In 1991, that understanding was tested in blood.

By mid-1991, Sri Lanka was deep into Eelam War II, a phase of the protracted conflict marked by increasing intensity and escalating ambitions. The Sri Lankan military’s footprint in the Jaffna Peninsula had shrunk dramatically following its withdrawal from Jaffna Fort in September 1990. After that retreat, the Army retained control over only two critical enclaves: The High Security Zone at Palaly and the Elephant Pass military complex. The latter was not merely a base; it was a linchpin. Its fall would have effectively severed the peninsula from the rest of the island and handed the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) a decisive psychological and strategic victory.

The Elephant Pass military base was a sprawling complex defensive system rather than a single installation. It consisted of one main camp supported by four satellite camps, spread across a vast area approximately 10 kilometres wide and 23 kilometres long. Trenches, bunkers, minefields, forward defence lines, and artillery positions formed concentric layers of defence, designed to withstand infiltration rather than a full-scale conventional assault.

Yet, by 1991, the LTTE had transformed. No longer content with guerrilla tactics alone, it sought to demonstrate its ability to fight and win conventional battles. Elephant Pass would become the proving ground for this ambition.

On 10th July 1991, the calm of the arid northern landscape was shattered. At dawn, the LTTE launched what would become the largest offensive operation in its history up to that point. Elephant Pass came under a coordinated, multi-directional siege. The base was commanded by Sanath Karunaratne, then a Major and later to rise to the rank of Major General. Under his command were approximately 800 Sri Lankan soldiers, who would soon find themselves completely encircled.

The LTTE leadership, under Velupillai Prabhakaran, had grand expectations. Prabhakaran publicly proclaimed the offensive as the “Mother of All Battles”, confident that the fall of Elephant Pass was inevitable. It was not mere bravado; the LTTE had mobilised thousands of fighters—both male and female cadres—supported by heavy mortars, machine guns, rocket launchers, and a range of improvised armoured vehicles.

The initial assault came from the southern axis, advancing from Paranthan. The attack opened with intense mortar and artillery fire directed at the outer defence lines, followed by wave after wave of infantry assaults. In fact, on the very first day the LTTE captured a few bunkers held by the troops. Troops fell back to the second line of defence. What shocked defenders most, however, was the appearance of a massive armour-plated bulldozer advancing relentlessly toward the forward defences.

This bulldozer was thought to have been captured earlier from the cement factory at Kankesanthurai (KKS) and later modified in LTTE workshops in the Wanni. Thick iron plates had been welded onto its exterior, transforming it into a crude but formidable armoured vehicle. Inside were four LTTE cadres, protected from small arms fire and even anti-tank weapons to a remarkable degree.

Missiles and rocket-propelled grenades fired at the vehicle failed to halt its advance. As the ‘suicide’ vehicle crushed through obstacles and earthworks, the threat became existential. If the armoured vehicle breached the inner defences, it would have opened the camp to catastrophic assault by the advancing fighters of the LTTE.

At that critical moment, one soldier made a decision that would forever alter the course of the battle and Sri Lankan military history, an act of supreme sacrifice.

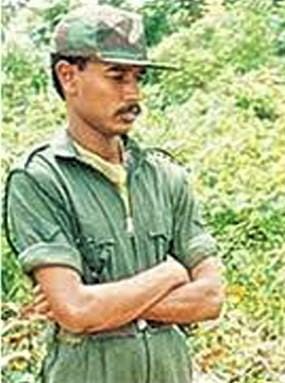

Gamini Kularatne, a Lance Corporal of the 6th Battalion, Sri Lanka Sinha Regiment, recognised the danger with chilling clarity. Acting entirely on his own initiative, and with full knowledge that it would almost certainly cost him his life, he ran toward the advancing bulldozer.

Under heavy enemy fire, he reached the rear of the vehicle, climbed the ladder affixed to its armoured body, and dropped a grenade into the interior compartment. The explosion killed all four LTTE cadres inside. The bulldozer veered off course, crashed into a structure within the camp perimeter, and came to a halt. In the fierce crossfire that followed, Lance Corporal Kularatne was killed.

His action saved Elephant Pass at its most vulnerable moment. Had the bulldozer broken through, the base might well have fallen within hours. From that day onward, he became immortalised as “Hasalaka Gamini”, a symbol of self-sacrifice and courage beyond measure.

Later, he would be posthumously promoted and awarded the Parama Weera Vibhushanaya, the highest award for gallantry in Sri Lanka. He was the first recipient of this honour and was officially declared a National Hero.

Almost simultaneously with the southern thrust, two smaller armoured vehicles attempted to breach the defences from the northern axis. This time, Sri Lankan soldiers managed to destroy them using rocket-propelled grenades, halting the advance at the forward defence line. Despite these setbacks, the LTTE intensified its assault. Mortar fire rained down relentlessly. Eventually, the Rest House camp in the southern sector fell to the LTTE. Sri Lankan troops were forced to withdraw to secondary defensive positions, sustaining heavy casualties in the process. The noose tightened.

Attempts by the Sri Lanka Air Force to land helicopters inside the base were repeatedly aborted due to heavy anti-aircraft fire. Aerial resupply became the only lifeline, and even then, only about 60 percent of airdropped supplies landed within the camp perimeter. Food, ammunition, and medical supplies ran dangerously low. Wounded soldiers accumulated, and medical evacuation was sporadic at best. Yet, morale within the camp held—anchored by the knowledge that losing Elephant Pass was not an option.

By mid-July, the situation had become critical. The loss of Elephant Pass would have been disastrous—not only militarily, but politically and psychologically. The immediate priority was clear, the besieged garrison had to be relieved. The only feasible approach route lay from the East, through Vettilaikerni 12 km away from EPS, as all land routes were heavily mined or controlled by the LTTE. What followed was the most ambitious amphibious operation in the history of the Sri Lanka Army.

The rescue mission was codenamed Operation Balavegaya, literally, “Operation Force of Strength.”. The operation was commanded by Denzil Kobbekaduwa, the General Officer Commanding the 2nd Division, with Vijaya Wimalaratne serving as the Amphibious Task Force Commander. Together, they coordinated a joint operation involving the Army, Navy, and Air Force, mobilising nearly 10,000 troops.

Participating units included seasoned battalions from the Sri Lanka Light Infantry, Sri Lanka Sinha Regiment, Gemunu Watch, Gajaba Regiment, supported by the Sri Lanka Armoured Corps and Sri Lanka Artillery. The Sri Lanka Navy assembled a flotilla of landing craft, gunboats, and fast attack vessels. The flagship SLNS Wickrama carried Major General Kobbekaduwa, while Brigadier Wimalaratne coordinated naval and air operations from SLNS Edithara.

Anticipating a sea- borne offensive the LTTE had already deployed a substantial fighting force consisting of male and female cadres along the beaches of Vettilaikerni and Kaddaikadu. Several fighting units engaged in the fighting at the Elephant Pass base were also despatched to the new front.

The first seaborne landing attempt at Vettilaikerni on 15 July 1991 at 14:30 hours met fierce resistance. Recognising the risk of unacceptable casualties, Brigadier Wimalaratne made the crucial decision to delay the landing. A second attempt was launched at 18:00 hours, under cover of darkness, with naval gunfire and close air support from SIAI-Marchetti SF-260 aircraft. This time, the first wave successfully established a beachhead, though at heavy cost. Within 24 hours, the remaining troops had landed.

What followed was eighteen days of brutal, grinding combat. The terrain between Vettilaikerni and Elephant Pass—sand dunes, thorny scrub, and Palmyrah palms—offered little cover. Minefields, ambushes, and sniper fire slowed every advance. The LTTE employed deception tactics, including plaster-of-Paris dummy fighters positioned to draw fire and confuse advancing troops.

Near Mulliyan Kovil, northwest of Vettilaikerni, fighting reached exceptional intensity. According to Sarath Munasinghe, the military spokesman at that time, who later documented the battle in A Soldier’s Version, the LTTE mounted repeated counterattacks to recover a hidden cache of gold near the temple—succeeding briefly before withdrawing with the valuables.

In the third week, armoured elements—including Alvis Saladin armoured cars, Saracen and Buffel APCs—finally broke through enemy lines despite suffering mine losses. On 4 August 1991, forward elements of the task force reached the beleaguered Elephant Pass garrison, singing Hela Jathika Abhimane.

The siege was broken.

By 9 August 1991, the LTTE had withdrawn tactically, having suffered devastating losses. According to multiple sources, including Australian born Adele Ann Balasingham, one-time leader of the Women Fighters of the LTTE, 573 LTTE cadres, including 123 women fighters, were killed. She praises the heroic role played by the The Women Fighters of the Liberation Tigers in her book published in Jaffna in 1993 and also mentions that over a thousand armed forces personnel died in battle, a claim denied by the Defence Forces. Sri Lanka Army lost 202 soldiers, including several senior officers as reported in “A Soldiers Version” by Major General Munasinghe who later describes the moment of victory as “the biggest defeat inflicted on the LTTE up to that time.” Across the country, civilians sent food, sweets, and messages of support to frontline troops. Banners praising the soldiers appeared in towns and villages nationwide.

At the time, I was one of the surgeons on duty at the hospital at the Palaly Military Base.

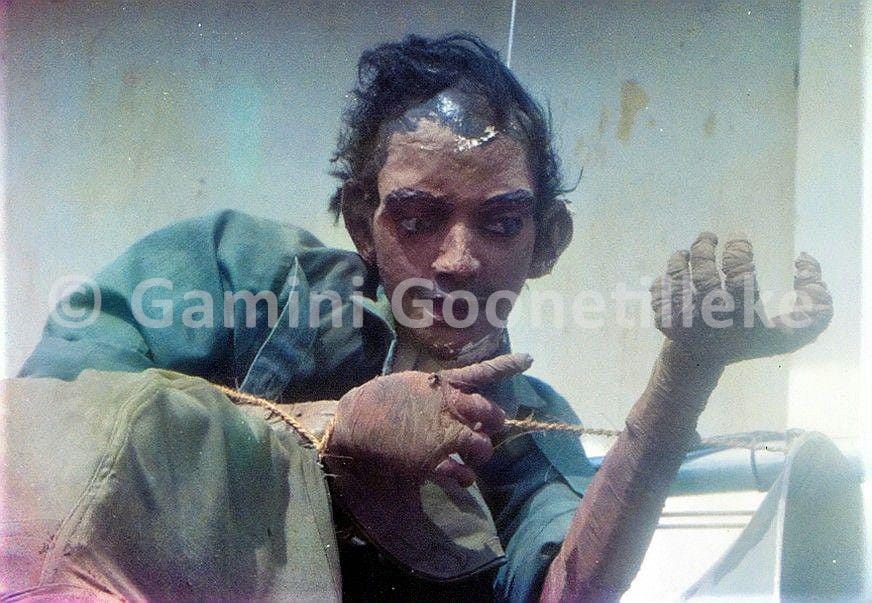

Casualties arrived in relentless waves—blast injuries, gunshot wounds, traumatic amputations, burns, and bodies riddled with shrapnel driven deep into muscle and bone. The operating theatre in a resource limited hospital functioned without pause; exhaustion was constant, urgency absolute.

I vividly recall a phone call from the commanding officer, Sanath Karunaratne, seeking immediate advice. A soldier lay critically wounded in the field, his limb mangled beyond salvage. Massive bleeding threatened his life, yet evacuation was impossible—the skies were unsafe, and no aircraft could be deployed.

With time running out, I advised that an emergency field amputation be performed. It was a stark, last-resort decision, made not to save a limb, but to save a life. The limb was removed under the harshest conditions imaginable, haemorrhage was controlled, and the soldier survived. When conditions later permitted, he was transported to the base hospital, where a formal surgical revision was carried out under controlled conditions.

Some casualties were airlifted directly to Anuradhapura General Hospital when their injuries exceeded our capacity for care. In those moments, medicine was stripped to its essentials—decisions were immediate, imperfect, and irreversible, yet guided always by one overriding purpose: to keep the wounded alive long enough to give them a chance at recovery.

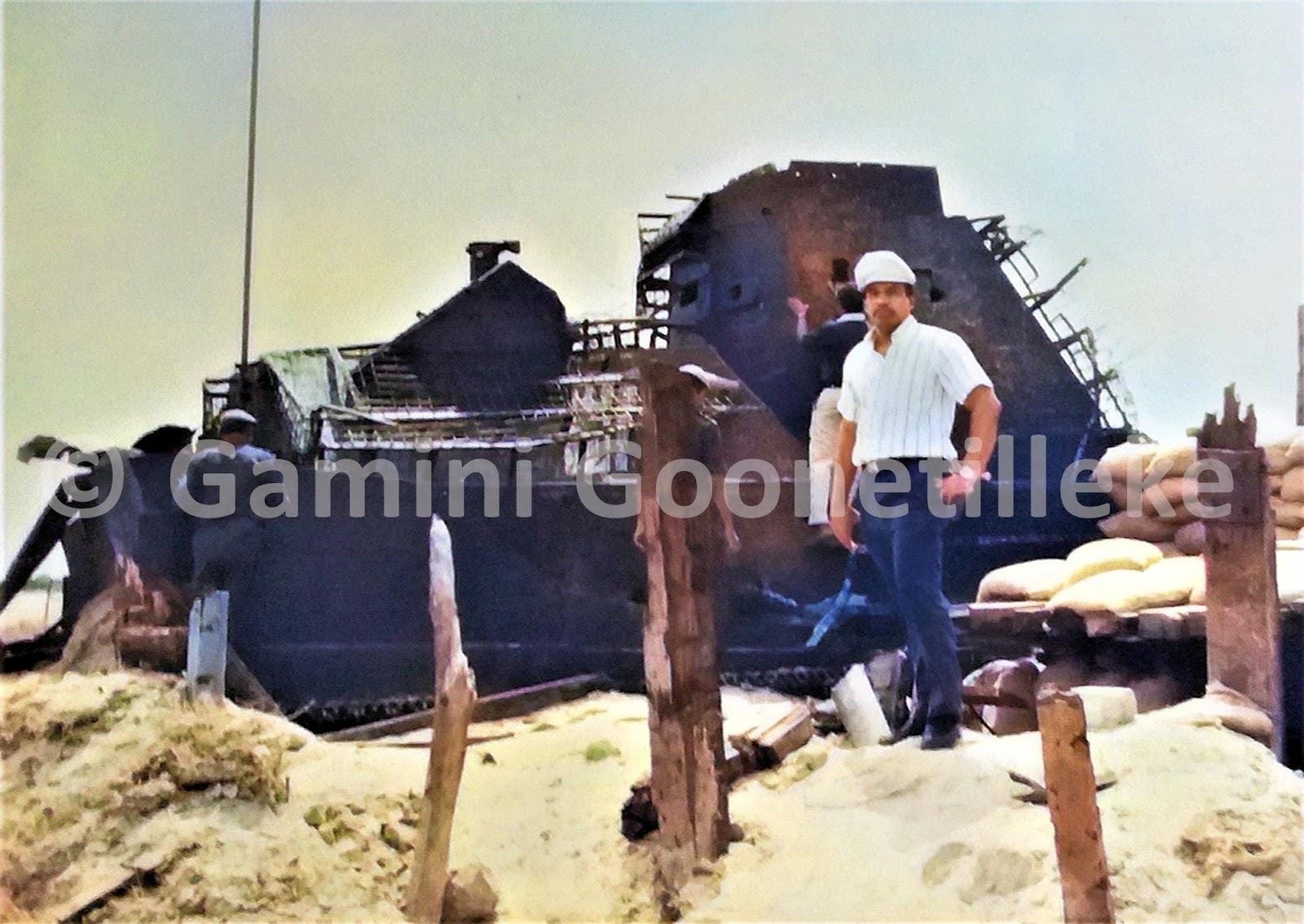

After the battle, I accompanied the two commanding officers on a helicopter flight back to Elephant Pass. The silence after weeks of combat was eerie. The ground was littered with shell fragments, bullet casings, and the remains of shattered structures. At the site where the armoured bulldozer had crashed, I climbed the ladder at the rear of the vehicle and looked inside. The four bodies of the LTTE cadres were still there—a stark, unforgettable testament to the moment when the battle turned. The photographs I took during that visit of the wreckage, the terrain, and the remnants of war, are, I believe, of genuine historical value.

Today, a memorial museum stands at Paranthan displaying the wreckage of the armour plated bulldozer and a statue of Gamini Kularatne visible to all who travel the A9 highway, commemorating the Lance Corporal, posthumously promoted Corporal. A statue also stands in his hometown of Hasalaka, reminding future generations of the price paid for duty.

The Battle for Elephant Pass, 1991, remains one of the most significant military engagements in Sri Lanka’s modern history—a battle defined not only by strategy and firepower, but by courage, sacrifice, and resilience.

It is, undeniably, a part of the history of Sri Lanka.